Temporal Decoupling and Micro-Latency Regulation in Simultaneous Interpreting:

A Multilevel Perspective on Parallel Cognitive Processing

27 June 2025, Bangkok – Simultaneous interpreting is among the most cognitively demanding linguistic activities. It involves not merely instantaneous translation but the management of continuous, asynchronous cognitive operations across input, processing, and output streams. This article introduces the concepts of temporal decoupling and micro-latency regulation to explain how professional interpreters coordinate unsynchronized processing loops under time pressure. Drawing on established models in interpreting theory, psycholinguistics, and working memory research, we argue that simultaneous interpreting is best understood as a real-time synchronization of multiple temporally disjointed operations. The implications extend to interpreter training, performance assessment, and interface design for interpreter support technologies.

Keywords: simultaneous interpreting, temporal decoupling, micro-latency, working memory, cognitive load, real-time processing

1. Introduction

Simultaneous interpreting (SI) has long been recognized as a high-stakes, high-speed bilingual task that places extreme demands on cognition. The interpreter must listen to a source language message, process its content, and produce an equivalent message in the target language, all while the speaker continues uninterrupted. Contrary to the common perception that SI is simply “speaking while listening,” the task requires the real-time coordination of temporally unsynchronized processes across multiple cognitive systems (Setton, 1999). In recent decades, cognitive modeling of SI has gained traction, helping to elucidate the neural and procedural architecture that supports this complex activity.

2. Theoretical Framework: Temporal Decoupling

Temporal decoupling refers to the separation of cognitive processes across distinct time streams. In SI, input comprehension, internal reformulation, and output delivery do not occur in linear succession but overlap and drift apart across sliding temporal windows (Gile, 2009). The interpreter must manage each stream independently while continuously recalibrating their relationships. Crucially, micro-latency regulation—the fine-grained control over the timing gap between each processing level—is a marker of expert interpreting performance.

3. Parallel Cognitive Operations in Simultaneous Interpreting

Setton (1999) proposed a multichannel processing model that reflects the interpreter’s need to operate across multiple cognitive channels in real time. The main components include:

3.1 Auditory Perception and Semantic Segmentation

Interpreters must identify meaningful segments from unfolding speech, often before full syntactic closure. Prosodic cues, syntactic frames, and discourse expectations guide this early segmentation.

3.2 Working Memory Buffering

Gile’s (2009) Effort Model emphasizes the limited capacity of working memory. Interpreters store partial information in a transient buffer while awaiting disambiguation or full semantic resolution.

3.3 Predictive Processing

Interpreters draw upon context, frequency effects, and prior knowledge to anticipate upcoming lexical or syntactic items (Seeber, 2011). This reduces cognitive strain and enables smoother delivery.

3.4 Self-Monitoring and Feedback Loops

Interpreters listen to their output to check for omissions, disfluencies, or syntactic mismatches. This auditory feedback loop is unique to SI and essential for quality control.

3.5 Prosodic Adaptation and Target Reformulation

Professional SI involves adapting the target message to the prosodic norms of the target language, even when syntax differs. This contributes to the naturalness and rhetorical effectiveness of the interpretation (Collard et al., 2018).

4. Ear-Voice Span and Risk of Semantic Collapse

The ear-voice span (EVS)—the time gap between hearing a source segment and beginning its interpretation—is not static. Interpreters must adjust their EVS dynamically based on speaker speed, cognitive load, and linguistic complexity. A span that is too short risks insufficient processing; too long, and working memory overload may lead to semantic collapse—the breakdown of comprehension under pressure (Viezzi, 1992). Expert interpreters constantly monitor this balance, shifting between strategies such as summarization, omission, or delay to maintain coherence.

5. Conclusion

Simultaneous interpreting is not a single-process task but a dynamic synchronization of asynchronous cognitive operations. Mastery in SI lies in the interpreter’s ability to modulate temporal relationships between comprehension, reformulation, and production, each with its micro-latency demands. Understanding these mechanisms has critical implications for interpreter training curricula, performance evaluation, and the development of intelligent tools that support interpreting in real time. Future research should continue to integrate insights from neuroscience, psycholinguistics, and cognitive ergonomics to advance the field.

References

- Collard, C., Defrancq, B., & Plevoets, K. (2018). Prosodic adaptations in simultaneous interpreting: The role of anticipation and ear-voice span. The Interpreters’ Newsletter, 23(1), 1–25.

- Gile, D. (2009). Basic concepts and models for interpreter and translator training (Rev. ed.). John Benjamins.

- Seeber, K. G. (2011). Cognitive load in simultaneous interpreting: Existing theories – new models. Interpreting, 13(2), 176–204. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.13.2.04see

- Setton, R. (1999). Simultaneous interpretation: A cognitive-pragmatic analysis. John Benjamins.

- Viezzi, M. (1992). Quality in simultaneous interpreting: A survey. In C. Dollerup & A. Loddegaard (Eds.), Teaching translation and interpreting: Training, talent and experience (pp. 157–164). John Benjamins.

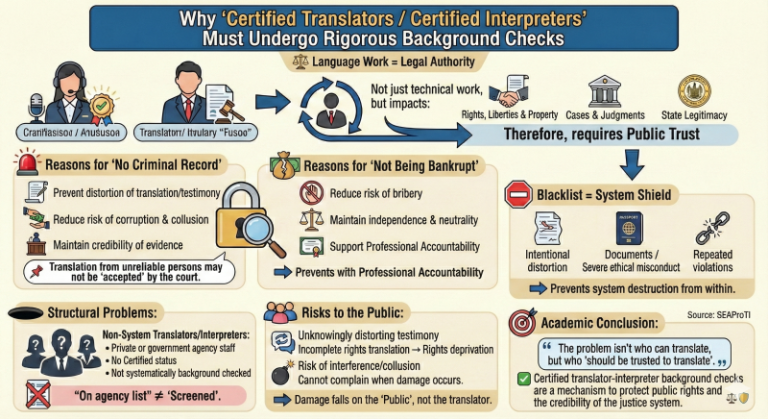

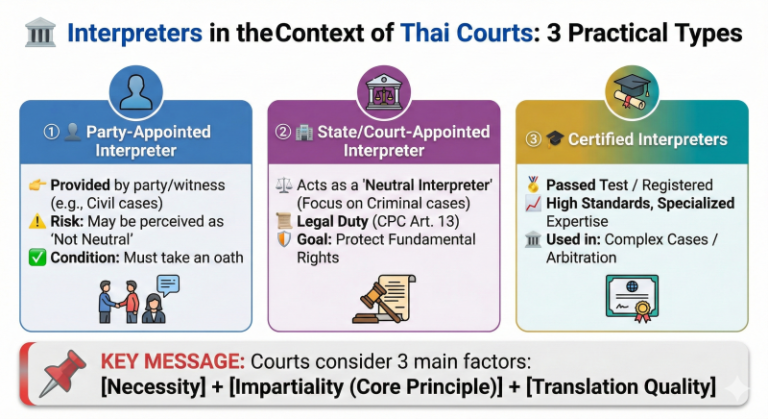

SEAProTI’s certified translators, translation certification providers, and certified interpreters:

The Southeast Asian Association of Professional Translators and Interpreters (SEAProTI) has officially announced the criteria and qualifications for individuals to register as “Certified Translators,” “Translation Certification Providers,” and “Certified Interpreters” under the association’s regulations. These guidelines are detailed in Sections 9 and 10 of the Royal Thai Government Gazette, issued by the Secretariat of the Cabinet under the Office of the Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Thailand, dated July 25, 2024, Volume 141, Part 66 Ng, Page 100.

To read the full publication, visit the Royal Thai Government Gazette

การแยกเวลาเชิงชั้นและการควบคุมไมโครเลเทนซีในการล่ามพูดพร้อม: มุมมองด้านการประมวลผลขนานในสมองมนุษย์

27 มิถุนายน 2568, กรุงเทพมหานคร – การล่ามพูดพร้อม (simultaneous interpreting) เป็นกระบวนการที่ซับซ้อนและใช้การทำงานของสมองหลายระบบในเวลาเดียวกัน ไม่ใช่เพียงการแปลแบบทันที แต่เป็นการบริหารจัดการข้อมูลต้นฉบับ การวิเคราะห์เนื้อหา และการถ่ายทอดสารอย่างเป็นธรรมชาติ ภายใต้เงื่อนไขของการประมวลผลแบบไม่พร้อมกัน (asynchronous processing) บทความนี้เสนอแนวคิดเรื่อง “การแยกเวลาเชิงชั้น” (temporal decoupling) และ “การควบคุมไมโครเลเทนซี” (micro-latency regulation) เพื่ออธิบายกลไกการทำงานของล่ามพูดพร้อมในระดับจุลภาค โดยอ้างอิงจากทฤษฎีด้านการแปล การประมวลผลภาษาธรรมชาติ และจิตวิทยาด้านความสนใจ

คำสำคัญ: ล่ามพูดพร้อม, การแยกเวลา, ไมโครเลเทนซี, ความจำทำงาน, การประมวลผลภาษาขนาน

บทนำ

การล่ามพูดพร้อมถือเป็นหนึ่งในรูปแบบการแปลที่มีความซับซ้อนสูงสุด ล่ามต้องถ่ายทอดสารจากภาษาหนึ่งไปสู่อีกภาษาหนึ่งในขณะที่ผู้พูดต้นฉบับยังไม่พูดจบ ซึ่งเป็นการกระทำที่ท้าทายทั้งในแง่ของความเร็ว ความแม่นยำ และการคงไว้ซึ่งจังหวะการสื่อสารตามธรรมชาติ (Setton, 1999) การศึกษาระบบประมวลผลภายในสมองล่ามจึงกลายเป็นหัวข้อที่ได้รับความสนใจจากนักภาษาศาสตร์ นักแปล และนักประสาทวิทยาในช่วงหลายทศวรรษที่ผ่านมา

กรอบแนวคิด: การแยกเวลาเชิงชั้น

“การแยกเวลาเชิงชั้น” (temporal decoupling) หมายถึงการดำเนินกระบวนการทางความคิดที่ไม่พร้อมกันในเชิงเวลา กล่าวคือ ล่ามพูดพร้อมต้องแยกระหว่างการฟัง (input), การวิเคราะห์ (processing) และการถ่ายทอด (output) ให้อยู่ในลูปที่ทำงานขนานกัน (Gile, 2009) แต่ละลูปจะมี “เลเทนซี” หรือความหน่วง (latency) ที่ต่างกัน และความสามารถในการควบคุมความต่างนี้ในระดับจุลภาคหรือไมโครเลเทนซี (micro-latency) ถือเป็นปัจจัยสำคัญของความเชี่ยวชาญในการล่าม

ระบบการทำงานแบบขนานของล่ามพูดพร้อม

Setton (1999) ได้เสนอโมเดล “multichannel processing” ซึ่งอธิบายว่าล่ามพูดพร้อมต้องประมวลผลข้อมูลในหลายช่องทางพร้อมกัน ได้แก่:

- การรับรู้เสียงและการแยกความหมาย (Auditory Perception & Segmentation): ล่ามต้องตัดสินใจแบ่งประโยคและวลีจากสัญญาณเสียงที่ยังไม่สมบูรณ์ และคาดเดาความหมายล่วงหน้า

- ความจำทำงาน (Working Memory): Gile (2009) ได้เสนอใน “Effort Model” ว่าการเก็บข้อมูลที่ยังไม่สามารถแปลได้ทันทีใน working memory คือหนึ่งใน effort ที่สำคัญที่สุด

- การคาดการณ์เชิงไวยากรณ์และความหมาย (Predictive Processing): ตามแนวคิดของ Seeber (2011) ล่ามต้องพึ่งพาความรู้เดิมและบริบทเพื่อลดภาระในการประมวลผลจริง โดยเฉพาะเมื่อโครงสร้างไวยากรณ์ของต้นฉบับยังไม่สมบูรณ์

- การติดตามผลลัพธ์ของตนเอง (Self-Monitoring): ล่ามต้องฟังเสียงของตนเองในขณะพูดเพื่อปรับจังหวะ น้ำเสียง และโครงสร้างให้น่าเชื่อถือ

- การควบคุมเสียงพูดให้เหมาะสม (Prosodic Matching): การล่ามที่ดีไม่ใช่เพียงการถ่ายทอดเนื้อหา แต่รวมถึงการรักษาจังหวะของภาษาเป้าหมายให้ใกล้เคียงกับภาษาแม่ของผู้ฟัง (Collard et al., 2018)

- การจัดการช่วงหู-เสียง (Ear-Voice Span) และความเสี่ยงของการพังทลายทางความหมาย: ช่วงเวลา Ear-Voice Span (EVS) คือช่วงเวลาระหว่างการได้ยินต้นฉบับกับการเริ่มต้นพูดคำแปล EVS ที่ยาวเกินไปจะเพิ่มภาระใน working memory ขณะที่ EVS ที่สั้นเกินไปอาจทำให้เนื้อหาขาดความชัดเจน การปรับ EVS จึงเป็นกลไกสำคัญในการรักษาความสมดุลระหว่างคุณภาพและความเร็ว (Viezzi, 1992)

บทสรุป

การล่ามพูดพร้อมไม่ใช่เพียงการแปลแบบทันที แต่คือการบริหารข้อมูลที่ไหลเข้าและออกในลูปเวลา 3 ระดับอย่างสอดประสาน ล่ามต้องมีความสามารถในการควบคุมเลเทนซีในระดับจุลภาค การเข้าใจกลไกเหล่านี้จะเป็นประโยชน์อย่างยิ่งต่อการออกแบบหลักสูตรฝึกอบรม การประเมินความสามารถ และการพัฒนาเทคโนโลยีสนับสนุนการล่ามในอนาคต

บรรณานุกรม (References)

- Collard, C., Defrancq, B., & Plevoets, K. (2018). Prosodic adaptations in simultaneous interpreting: The role of anticipation and ear-voice span. The Interpreters’ Newsletter, 23(1), 1–25.

- Gile, D. (2009). Basic concepts and models for interpreter and translator training (Rev. ed.). John Benjamins.

- Seeber, K. G. (2011). Cognitive load in simultaneous interpreting: Existing theories – new models. Interpreting, 13(2), 176–204. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.13.2.04see

- Setton, R. (1999). Simultaneous interpretation: A cognitive-pragmatic analysis. John Benjamins.

- Viezzi, M. (1992). Quality in simultaneous interpreting: A survey. In C. Dollerup & A. Loddegaard (Eds.), Teaching translation and interpreting: Training, talent and experience (pp. 157–164). John Benjamins.

เกี่ยวกับนักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรองของสมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้

สมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ (SEAProTI) ได้ประกาศหลักเกณฑ์และคุณสมบัติผู้ที่ขึ้นทะเบียนเป็น “นักแปลรับรอง (Certified Translators) และผู้รับรองการแปล (Translation Certification Providers) และล่ามรับรอง (Certified Interpreters)” ของสมาคม หมวดที่ 9 และหมวดที่ 10 ในราชกิจจานุเบกษา ของสำนักเลขาธิการคณะรัฐมนตรี ในสำนักนายกรัฐมนตรี แห่งราชอาณาจักรไทย ลงวันที่ 25 ก.ค. 2567 เล่มที่ 141 ตอนที่ 66 ง หน้า 100 อ่านฉบับเต็มได้ที่: นักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรอง