Misinterpretation of the Requirement for “Court-Registered Interpreters”:

Legal Facts and Cautions in Civil Proceedings

2 July 2025, Bangkok – In Thai civil proceedings, there has been a persistent misunderstanding regarding the use of interpreters—particularly the notion that only “court-registered interpreters” are permitted to interpret during trials. This misconception often leads to an infringement on a party’s right to bring their own interpreter and, in some cases, is used as a means to influence the outcome of proceedings. This article clarifies the legal framework regarding interpreters in civil cases, dispels incorrect interpretations, and provides recommendations to ensure fairness and due process.

Interpretation services play a vital role in civil proceedings, ensuring equal access to justice for parties who do not understand Thai. According to Section 46 of the Thai Civil Procedure Code, the party concerned is responsible for providing their own interpreter—not the court. Therefore, any claim that only interpreters “registered with the court” are allowed is legally unfounded and can lead to undue restriction of a litigant’s procedural rights.

Legal Framework

Section 46 of the Civil Procedure Code explicitly states:

“If a party or a person involved in the case cannot speak or understand Thai, or is mute or deaf and unable to read or write, the party concerned must provide an interpreter” (Civil Procedure Code, 1992).

There is no legal provision requiring that interpreters must be “registered with the court” or certified by a specific authority. Instead, the law grants the court discretionary power to approve the interpreter brought by the party, based on appropriateness in each case.

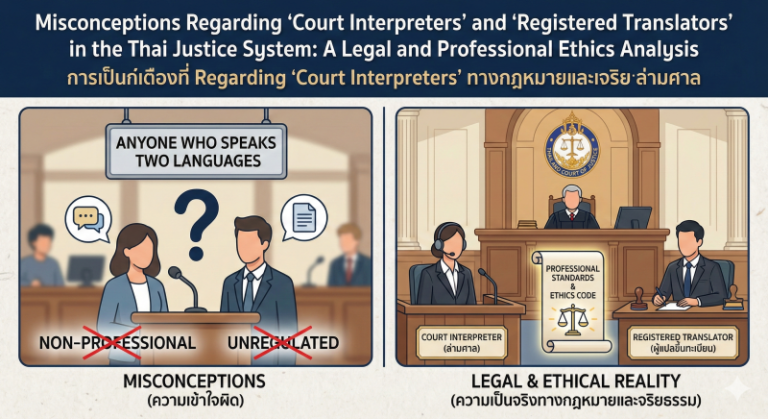

Misuse and Misinterpretation in Practice

In practice, it is not uncommon for certain parties—such as opposing counsel or even some court officials—to insist that only “registered court interpreters” may interpret. This assertion lacks legal basis and may be strategically used to exclude interpreters perceived to be neutral or aligned with the other party. In some cases, such claims serve as a means to influence the interpretation of witness testimony or the course of proceedings, which can jeopardize the fairness of the trial.

The Court’s Supervisory Role

While the court is not obligated to provide an interpreter, it retains the authority to approve or reject interpreters presented by the parties. If the court finds that an interpreter has a conflict of interest, lacks impartiality, or is incompetent, it may prohibit that interpreter from participating in certain phases of the trial—for example, during witness examination. This judicial discretion is based on ensuring fairness, rather than a requirement for official registration.

Policy Recommendations

It is essential to foster accurate understanding among legal professionals and court officials about the rights of litigants to appoint interpreters. There is no statutory requirement that an interpreter must be “court-registered.” Professional associations—such as SEAProTI—should take a proactive role in promoting interpreter ethics and professional standards, while also providing guidance to courts and the public on lawful interpreter use in civil proceedings.

- Office of the Council of State. (1992). Civil Procedure Code of Thailand. Bangkok: Office of the Council of State.

Tamura, T. (2019). Interpreter’s neutrality and agency: A professional dilemma in courtroom interpreting. The International Journal for Court - Administration, 10(3), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.36745/ijca.312

- SEAProTI. (2024). Guidelines for Interpreter Ethics in Civil and Administrative Proceedings. Southeast Asian Association of Professional Translators and Interpreters.

SEAProTI’s certified translators, translation certification providers, and certified interpreters:

The Southeast Asian Association of Professional Translators and Interpreters (SEAProTI) has officially announced the criteria and qualifications for individuals to register as “Certified Translators,” “Translation Certification Providers,” and “Certified Interpreters” under the association’s regulations. These guidelines are detailed in Sections 9 and 10 of the Royal Thai Government Gazette, issued by the Secretariat of the Cabinet under the Office of the Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Thailand, dated July 25, 2024, Volume 141, Part 66 Ng, Page 100.

To read the full publication, visit: the Royal Thai Government Gazette

การตีความผิดเกี่ยวกับ “ล่ามศาลขึ้นทะเบียน”: ข้อเท็จจริงทางกฎหมายและข้อพึงระวังในกระบวนพิจารณาคดีแพ่ง

2 กรกฎาคม 2568, กรุงเทพมหานคร – ในกระบวนการพิจารณาคดีแพ่งในประเทศไทย มีความเข้าใจที่คลาดเคลื่อนเกี่ยวกับการใช้ล่าม โดยเฉพาะการอ้างว่า “ต้องเป็นล่ามศาลที่มีทะเบียนเท่านั้น” จึงจะสามารถทำหน้าที่แปลในการพิจารณาคดีได้ ความเข้าใจเช่นนี้นำไปสู่การจำกัดสิทธิของคู่ความในการจัดหาล่ามของตนเอง และในบางกรณีอาจเป็นกลไกในการแสวงหาผลประโยชน์จากผลแห่งคดีโดยไม่ชอบด้วยกฎหมาย บทความนี้จึงมุ่งชี้แจงข้อเท็จจริงทางกฎหมาย พร้อมทั้งเสนอแนะแนวปฏิบัติที่ควรเป็นไปเพื่อความยุติธรรมที่แท้จริง

การใช้ล่ามในคดีแพ่งเป็นกลไกสำคัญในการอำนวยความยุติธรรมให้แก่คู่ความที่ไม่สามารถใช้ภาษาไทยได้ ตาม ประมวลกฎหมายวิธีพิจารณาความแพ่ง มาตรา 46 บัญญัติไว้อย่างชัดเจนว่า คู่ความฝ่ายที่เกี่ยวข้องเป็นผู้มีหน้าที่จัดหาล่ามเอง ไม่ใช่หน้าที่ของศาล เว้นแต่ศาลจะเห็นสมควร ด้วยเหตุนี้ การอ้างว่าล่ามจะต้องเป็น “ล่ามศาลที่มีทะเบียน” หรือ “ล่ามขึ้นทะเบียน” จึงไม่ปรากฏในบทบัญญัติแห่งกฎหมายแต่อย่างใด

ข้อเท็จจริงตามกฎหมาย

ตามมาตรา 46 วรรคท้าย ของประมวลกฎหมายวิธีพิจารณาความแพ่งระบุว่า:

“หากคู่ความหรือบุคคลใดที่เกี่ยวข้องในคดีไม่สามารถพูดหรือเข้าใจภาษาไทย หรือเป็นใบ้หรือหูหนวกและอ่านเขียนหนังสือไม่ได้ กฎหมายกำหนดให้ คู่ความฝ่ายที่เกี่ยวข้องเป็นผู้จัดหาล่าม” (ประมวลกฎหมายวิธีพิจารณาความแพ่ง, 2535)

จากถ้อยความข้างต้นจะเห็นได้ว่า กฎหมายมิได้กำหนดคุณสมบัติของล่ามไว้อย่างจำเพาะเจาะจง เช่น ต้องเป็น “ล่ามขึ้นทะเบียน” หรือได้รับการรับรองจากหน่วยงานใดโดยเฉพาะ แต่ให้อำนาจศาลในการใช้ดุลพินิจพิจารณาความเหมาะสมของล่ามเป็นรายกรณี

ปัญหาที่เกิดจากการตีความคลาดเคลื่อน

ในทางปฏิบัติ พบว่ามีบางฝ่ายในกระบวนการยุติธรรม เช่น ทนายความ ฝ่ายตรงข้าม หรือแม้แต่เจ้าหน้าที่บางราย อ้างว่าต้องใช้ล่ามศาลที่มีทะเบียนเท่านั้น จึงจะสามารถแปลในศาลได้ อันเป็นการสร้างเงื่อนไขโดยปราศจากฐานทางกฎหมาย และอาจมีผลกระทบต่อสิทธิในการดำเนินคดีของคู่ความ อีกทั้งยังอาจเป็นช่องทางในการกีดกันล่ามอิสระหรือเลือกใช้ล่ามที่ฝ่ายตนต้องการเพื่อให้เกิดผลต่อคำเบิกความหรือผลแห่งคดี ซึ่งขัดกับหลักความเป็นธรรม

ขอบเขตของศาลในการควบคุมการใช้ล่าม

แม้ศาลไม่มีหน้าที่ต้องจัดหาล่ามให้ แต่ศาลมีอำนาจในการควบคุมล่ามที่คู่ความนำมาใช้ หากเห็นว่าล่ามอาจมีผลประโยชน์ทับซ้อน ขาดความเป็นกลาง หรือไม่มีความสามารถเพียงพอ ศาลสามารถใช้ดุลพินิจไม่อนุญาตให้ล่ามทำหน้าที่ในบางช่วงของการพิจารณาคดีได้ ดังนั้น การใช้ล่ามจึงต้องผ่านการอนุมัติของศาลเป็นรายกรณี ไม่ใช่การอ้างทะเบียนล่ามอย่างไม่มีข้อเท็จจริงรองรับ

ข้อเสนอแนะเชิงนโยบาย

ควรมีการสร้างความเข้าใจที่ถูกต้องในกลุ่มผู้เกี่ยวข้องในกระบวนการยุติธรรม รวมถึงทนายความและเจ้าหน้าที่ศาลว่ากฎหมายให้สิทธิแก่คู่ความในการจัดหาล่ามเอง และไม่มีกฎหมายใดกำหนดว่าต้องใช้ “ล่ามที่ขึ้นทะเบียนกับศาล” ทั้งนี้ สมาคมวิชาชีพล่ามควรมีบทบาทส่งเสริมมาตรฐานวิชาชีพ ควบคู่ไปกับการให้ข้อมูลที่ถูกต้องแก่ศาลและสาธารณชน

อ้างอิง

- สำนักงานคณะกรรมการกฤษฎีกา. (2535). ประมวลกฎหมายวิธีพิจารณาความแพ่ง. กรุงเทพมหานคร: สำนักพิมพ์คณะกรรมการกฤษฎีกา.

- Tamura, T. (2019). Interpreter’s neutrality and agency: A professional dilemma in courtroom interpreting. The International Journal for Court Administration, 10(3), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.36745/ijca.312

- SEAProTI. (2024). Guidelines for Interpreter Ethics in Civil and Administrative Proceedings. Southeast Asian Association of Professional Translators and Interpreters.

สมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ (SEAProTI) ได้ประกาศหลักเกณฑ์และคุณสมบัติผู้ที่ขึ้นทะเบียนเป็น “นักแปลรับรอง (Certified Translators) และผู้รับรองการแปล (Translation Certification Providers) และล่ามรับรอง (Certified Interpreters)” ของสมาคม หมวดที่ 9 และหมวดที่ 10 ในราชกิจจานุเบกษา ของสำนักเลขาธิการคณะรัฐมนตรี ในสำนักนายกรัฐมนตรี แห่งราชอาณาจักรไทย ลงวันที่ 25 ก.ค. 2567 เล่มที่ 141 ตอนที่ 66 ง หน้า 100 อ่านฉบับเต็มได้ที่: นักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรอง