Interpreting Justice in Construction Disputes:

The Role of Interpreters in Malaysia’s CIPAA and Lessons for Thailand’s Statutory Adjudication Framework

Author: Wanitcha Sumanat

Affiliation: Southeast Asian Association of Professional Translators and Interpreters (SEAProTI)

Date: 19 October 2025

This article analyzes Malaysia’s experience under the Construction Industry Payment and Adjudication Act 2012 (CIPAA) through insights shared by Dato’ Mary Lim Thiam Suan, Director of the Asian International Arbitration Centre (AIAC), at the Thailand Institute of Justice (TIJ) on 17 October 2025. It discusses the legislative and institutional journey that shaped Malaysia’s statutory adjudication system and identifies the emerging role of interpreters as linguistic mediators in complex construction disputes. In the context of Thailand’s upcoming adjudication legislation, the paper highlights the importance of linguistic accuracy, procedural fairness, and professional interpreting in ensuring equitable access to justice for multilingual stakeholders in the construction industry.

Keywords: statutory adjudication, construction law, interpreters, language access, CIPAA 2012, Malaysia, Thailand

1. Introduction

Statutory adjudication provides a swift and cost-effective mechanism for resolving payment disputes in construction projects. However, in multilingual and multicultural jurisdictions like Malaysia and Thailand, linguistic clarity is a precondition for legal clarity. Every technical claim, progress payment, and evidential statement must be linguistically precise.

Dato’ Mary Lim (2025) recounted how Malaysia’s construction industry once suffered from systemic non-payment and a lack of accessible dispute resolution. The enactment of the Construction Industry Payment and Adjudication Act (CIPAA) in 2012 changed this landscape by ensuring a fast, enforceable mechanism for interim payment disputes. Yet, beyond legal reforms, the process relied heavily on linguistic mediation—through interpreters, translators, and bilingual adjudicators—especially when contractors, engineers, or witnesses used different working languages.

2. Malaysia’s Triple Reform Strategy

2.1 Legislative Foundation

CIPAA 2012 introduced a statutory right to payment for work done or services rendered under construction contracts. The Act applies to corporate entities within Malaysia but excludes private homeowners and government projects under moratorium (AIAC, 2023). Its purpose is to maintain cash flow and avoid project stagnation caused by delayed payments.

2.2 Judicial and Institutional Integration

To operationalize the Act, Malaysia undertook a “triple attack” approach (Lim, 2025):

- Enactment of legislation (CIPAA 2012).

- Establishment of a Construction Court with trained judges.

- Empowerment of AIAC to administer adjudication, appoint adjudicators, and train practitioners.

3. The Hidden Pillar: Interpreters in Construction Adjudication

3.1 Multilingual Realities in Adjudication

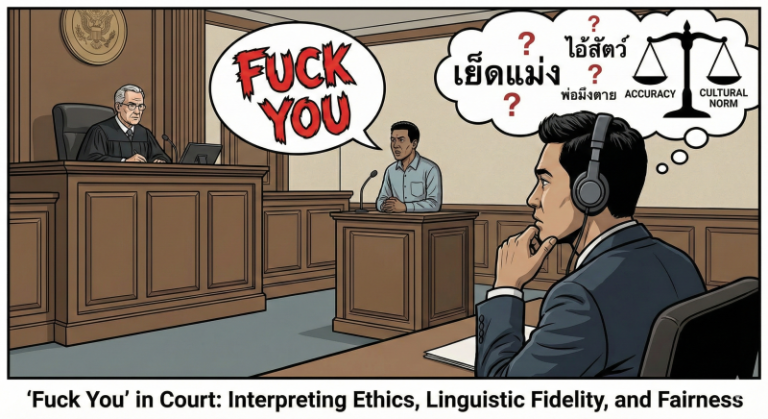

Malaysia’s construction sector is linguistically diverse—Malay, English, Mandarin, and Tamil are frequently used across projects. While the legal framework operates primarily in English, many contractors or subcontractors present documents and oral submissions in other languages.

In this environment, interpreters play an evidentiary and procedural role similar to that in arbitration or court proceedings. They ensure that:

- Technical witnesses’ testimonies are accurately interpreted for adjudicators.

- Contractual and financial terms are faithfully rendered between parties.

- Non-English-speaking stakeholders can meaningfully participate in proceedings.

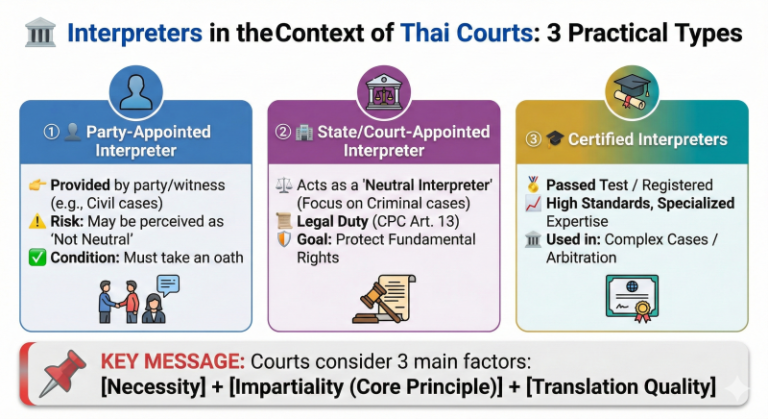

3.2 Interpreters as Agents of Access to Justice

According to Hale (2021), interpreters are “co-constructors of justice” in multilingual legal contexts. In adjudication, they help ensure equal participation, particularly for small and medium enterprises that may not have legal counsel fluent in English. Their neutrality and terminological precision contribute to what Zimanyi (2019) calls “procedural legitimacy.”

AIAC’s guidelines further recognize language assistance as a procedural safeguard. Interpreters in construction adjudication must understand both technical terminology (e.g., “retention sum,” “EOT,” “liquidated damages”) and legal principles (e.g., “quantum meruit,” “estoppel”).

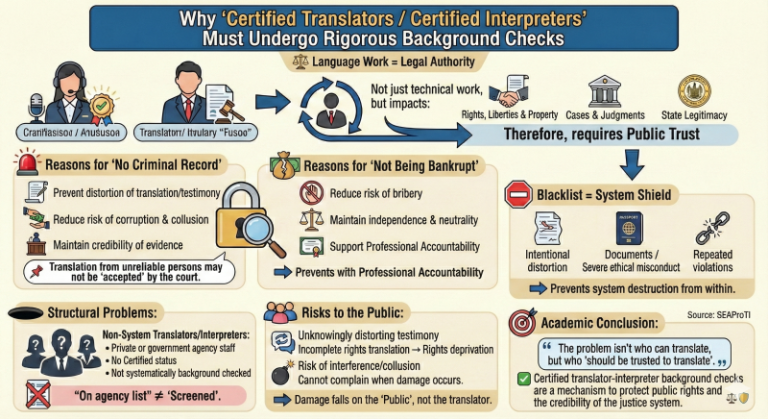

3.3 Ethical and Professional Considerations

Interpreters in adjudication bear similar ethical duties as in court:

- Accuracy — to prevent distortions of contractual intent.

- Confidentiality — as proceedings often involve sensitive commercial data.

- Impartiality — especially in hearings where both parties are unrepresented.

4. Operational Dynamics of Malaysia’s CIPAA

Under AIAC’s administration, an adjudicator is appointed within five working days, and a decision is rendered within ninety days. Lim (2025) revealed that Malaysia now has over 700 certified adjudicators, most of whom are engineers and quantity surveyors, with about 85–90% of decisions voluntarily complied with.

When hearings involve non-English-speaking parties, interpreters are engaged either directly by the parties or through AIAC’s roster, ensuring linguistic integrity in both documentation and oral proceedings. The process demonstrates the need for cross-disciplinary training—lawyers must understand technical terminology, and interpreters must grasp legal principles.

5. Lessons for Thailand’s Emerging Adjudication Framework

5.1 Legal-Structural Lessons

As Thailand moves toward enacting its own Construction Industry Payment and Adjudication Bill (TIJ, 2025), Malaysia’s experience offers three guiding lessons:

- Scope definition: Clearly delineate whether the Act covers progress payments, final accounts, and loss-and-expense claims.

- Judicial readiness: Train judges in construction law and adjudication procedure early.

- Institutional alignment: Empower an independent body—akin to AIAC—to manage adjudicator appointments, training, and procedural oversight.

Equally vital is Thailand’s recognition that language access is integral to adjudication fairness. The upcoming Thai model should:

- Institutionalize interpreter accreditation within the adjudication system.

- Include interpreters in training programs for adjudicators and judges.

- Provide multilingual procedural guidelines for parties, especially SMEs and foreign contractors.

6. Discussion: Interpreting as Infrastructure

Interpreters are not auxiliary participants but infrastructural actors in Malaysia’s adjudication ecosystem. They bridge linguistic and epistemic divides between engineers, lawyers, and adjudicators. As Pöchhacker (2016) argues, professional interpreting “constitutes an essential part of institutional communication.”

For Thailand, where adjudication will involve local and cross-border projects under ASEAN frameworks, interpreter professionalization must be a parallel reform to legislative enactment. SEAProTI, in cooperation with TIJ and the Engineering Institute of Thailand, could develop a Certification of Construction Adjudication Interpreters (CCAI) program modeled on AIAC’s technical training.

7. Conclusion

Malaysia’s CIPAA 2012 exemplifies how legal reform, institutional training, and linguistic inclusivity can transform an industry’s dispute culture. The role of interpreters—often overlooked in legal texts—proved essential in operationalizing fairness and understanding across languages and disciplines.

For Thailand, statutory adjudication must therefore integrate language access, interpreter training, and ethical regulation alongside legal drafting. As Lim (2025) emphasized, the ultimate purpose of adjudication is “to be heard and to move on”—a goal achievable only when every party, in every language, truly understands and is understood.

References

- AIAC. (2023). Construction Industry Payment and Adjudication Act (CIPAA) overview. Kuala Lumpur: Asian International Arbitration Centre.

- AIAC. (2024). Annual report on adjudication statistics and compliance rates. Kuala Lumpur: AIAC.

- Cheung, S., & Chong, H. (2020). Comparative adjudication regimes in Asia: Lessons for emerging economies. International Construction Law Review, 37(2), 111–136.

- Hale, S. (2021). The discourse of court interpreting: Discourse practices of the law, the witness, and the interpreter. Routledge.

- Lim, M. T. S. (2025, October 17). Experience of Malaysia in construction adjudication under CIPAA 2012. Lecture presented at the Thailand Institute of Justice (TIJ), Bangkok.

- Pöchhacker, F. (2016). Introducing interpreting studies (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Thailand Institute of Justice (TIJ). (2025). Seminar proceedings: Comparative perspectives on construction adjudication in ASEAN. Bangkok: TIJ.

- Yusoff, N. (2022). The impact of CIPAA 2012 on payment culture in the Malaysian construction industry. Asian Journal of Arbitration, 14(1), 67–88.

- Zimanyi, K. (2019). Interpreting and legitimacy in multilingual arbitration. Journal of Legal Linguistics, 12(2), 145–169.

About Certified Translators, Translation Certifiers, and Certified Interpreters of SEAProTI

The Southeast Asian Association of Professional Translators and Interpreters (SEAProTI) has formally announced the qualifications and requirements for registration of Certified Translators, Translation Certification Providers, and Certified Interpreters in Sections 9 and 10 of the Royal Gazette, published by the Secretariat of the Cabinet, Office of the Prime Minister of Thailand, on 25 July 2024 (Vol. 141, Part 66 Ng, p. 100). Certified Translators, Translation Certification Providers, and Certified Interpreters

The Council of State has proposed the enactment of a Royal Decree, granting registered translators and recognized translation certifiers from professional associations or accredited language institutions the authority to provide legally valid translation certification (Letter to SEAProTI dated April 28, 2025)

SEAProTI is the first professional association in Thailand and Southeast Asia to implement a comprehensive certification system for translators, certifiers, and interpreters.

Head Office: Baan Ratchakru Building, No. 33, Room 402, Soi Phahonyothin 5, Phahonyothin Road, Phaya Thai District, Bangkok 10400, Thailand

Email: hello@seaproti.com | Tel.: (+66) 2-114-3128 (Office hours: Mon–Fri, 09:00–17:00)

“เสียงแห่งความยุติธรรม”: บทบาทของล่ามในระบบการพิจารณาข้อพิพาทก่อสร้างของมาเลเซียภายใต้กฎหมาย CIPAA และบทเรียนสำหรับประเทศไทย

ผู้เขียน: วณิชชา สุมนัส

สังกัด: สมาคมนักแปลและล่ามวิชาชีพแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ (SEAProTI)

วันที่: ตุลาคม 2568

บทคัดย่อ

บทความนี้วิเคราะห์ประสบการณ์ของประเทศมาเลเซียภายใต้ พระราชบัญญัติการชำระเงินและการวินิจฉัยข้อพิพาทในอุตสาหกรรมก่อสร้าง พ.ศ. 2555 (Construction Industry Payment and Adjudication Act 2012 – CIPAA) ผ่านมุมมองของ ดาโต๊ะ แมรี ลิม เธียม ซวน (Dato’ Mary Lim Thiam Suan) อดีตผู้พิพากษาศาลฎีกาและผู้อำนวยการศูนย์อนุญาโตตุลาการระหว่างประเทศแห่งเอเชีย (AIAC) ซึ่งได้บรรยาย ณ สถาบันเพื่อการยุติธรรมแห่งประเทศไทย (TIJ) เมื่อวันที่ 17 ตุลาคม 2568

บทความนี้เน้นให้เห็นว่า การปฏิรูปกฎหมายเพียงอย่างเดียวไม่เพียงพอ หากปราศจาก “ความเข้าใจทางภาษา” และ “การสื่อสารข้ามวัฒนธรรมทางกฎหมาย” ที่ถูกต้อง โดยเฉพาะในกระบวนการระงับข้อพิพาทที่เกี่ยวข้องกับผู้รับเหมา วิศวกร และผู้ประกอบการจากหลายชาติ ล่ามมืออาชีพจึงมีบทบาทสำคัญในการคุ้มครองสิทธิ กระจายความเข้าใจ และทำให้ความยุติธรรมเกิดขึ้นได้จริงในบริบทพหุภาษาเช่นเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้

คำสำคัญ: การวินิจฉัยข้อพิพาท, กฎหมายก่อสร้าง, ล่าม, การเข้าถึงความยุติธรรม, มาเลเซีย, ประเทศไทย, CIPAA 2012

1. บทนำ

อุตสาหกรรมก่อสร้างเป็นภาคเศรษฐกิจที่มีมูลค่ามหาศาลและมีความซับซ้อนทางสัญญา ปัญหาการไม่ชำระเงินหรือชำระล่าช้ามักนำไปสู่ข้อพิพาทที่ส่งผลต่อเศรษฐกิจโดยรวม เพื่อแก้ไขปัญหานี้ ประเทศมาเลเซียได้ออก พระราชบัญญัติ CIPAA 2012 เพื่อสร้างระบบการวินิจฉัยข้อพิพาทที่รวดเร็วและมีผลบังคับใช้ในทางปฏิบัติ

อย่างไรก็ตาม มาเลเซียเป็นประเทศพหุภาษา ซึ่งมีทั้งภาษาอังกฤษ มลายู จีน และทมิฬใช้ในทางธุรกิจ การระงับข้อพิพาทจึงไม่ใช่เพียงเรื่องของ “กฎหมาย” เท่านั้น แต่เป็นเรื่องของ “ภาษา” และ “ความเข้าใจร่วม” ล่ามจึงทำหน้าที่เป็นสื่อกลางระหว่างภาษากฎหมาย ภาษาวิศวกรรม และภาษาช่าง ซึ่งเป็นหัวใจของความยุติธรรมในกระบวนการนี้

2. การปฏิรูปสามด้านของมาเลเซีย

ดาโต๊ะ แมรี ลิม (2025) กล่าวว่ามาเลเซียได้ดำเนิน “การโจมตีสามแนวทาง (Triple Attack)” เพื่อแก้ปัญหาความล่าช้าในการชำระเงินในวงการก่อสร้าง ได้แก่

- การปฏิรูปเชิงกฎหมาย – ออกกฎหมาย CIPAA 2012 เพื่อให้สิทธิทางกฎหมายแก่ผู้รับเหมาในการเรียกร้องเงินอย่างรวดเร็ว

- การปฏิรูปเชิงตุลาการ – จัดตั้ง “ศาลก่อสร้าง (Construction Court)” และอบรมผู้พิพากษาให้เข้าใจข้อพิพาทเชิงเทคนิค

- การปฏิรูปเชิงสถาบัน – มอบหมายให้ AIAC เป็นหน่วยงานกลางในการแต่งตั้งผู้วินิจฉัยข้อพิพาท (adjudicator) และบริหารจัดการกระบวนการทั้งหมด

ทั้งสามแนวทางต้องอาศัยความร่วมมือของนักกฎหมาย วิศวกร ผู้รับเหมา และ ล่ามมืออาชีพ ที่สามารถแปลความหมายทางเทคนิคและกฎหมายได้อย่างถูกต้องและเป็นกลาง

3. บทบาทของล่ามในระบบการวินิจฉัยข้อพิพาทของมาเลเซีย

3.1 พหุภาษากับความท้าทายของการสื่อสารทางกฎหมาย

อุตสาหกรรมก่อสร้างในมาเลเซียใช้หลายภาษาในการสื่อสาร ขณะที่เอกสารสัญญาส่วนใหญ่จัดทำเป็นภาษาอังกฤษ แต่ผู้รับเหมาหรือช่างฝีมือจำนวนมากใช้ภาษาอื่น ล่ามจึงต้องมีบทบาทในหลายขั้นตอน ได้แก่

- การแปลพยานหลักฐานและสัญญาให้ศาลหรือผู้วินิจฉัยเข้าใจ

- การถ่ายทอดคำเบิกความของผู้เชี่ยวชาญทางเทคนิค

- การอธิบายกระบวนการทางกฎหมายแก่คู่ความที่ไม่ใช้ภาษาอังกฤษ

3.2 ล่ามในฐานะ “ผู้ค้ำประกันสิทธิ” (Agents of Access to Justice)

Hale (2021) อธิบายว่า ล่ามในกระบวนการยุติธรรมไม่ใช่เพียงผู้แปลภาษา แต่เป็น “ผู้ร่วมสร้างความยุติธรรม” (co-constructors of justice) ในระบบการวินิจฉัยข้อพิพาท ล่ามจึงมีหน้าที่สำคัญในการทำให้ผู้มีส่วนได้เสียทุกฝ่าย “เข้าใจและถูกเข้าใจ” อย่างเท่าเทียม

3.3 มาตรฐานจรรยาบรรณและความรับผิดชอบ

ล่ามในงานก่อสร้างต้องยึดหลัก

- ความถูกต้องแม่นยำ (Accuracy) เพื่อไม่ให้ความหมายของสัญญาและพยานหลักฐานบิดเบือน

- ความเป็นกลาง (Impartiality) เพื่อไม่ให้เกิดผลประโยชน์ทับซ้อน

- การรักษาความลับ (Confidentiality) เนื่องจากคดีเกี่ยวข้องกับข้อมูลทางธุรกิจ

สมาคม SEAProTI และ AIIC ได้กำหนดแนวทางจรรยาบรรณที่ชัดเจนสำหรับ “ล่ามกฎหมายและล่ามอนุญาโตตุลาการ” เพื่อให้การทำงานในกระบวนการนี้มีมาตรฐานสากล

4. ระบบการทำงานของ AIAC ภายใต้กฎหมาย CIPAA

AIAC กำหนดให้แต่งตั้งผู้วินิจฉัยภายใน 5 วันทำการ และต้องมีคำตัดสินภายใน 90 วัน ซึ่งถือเป็นกระบวนการที่ “รวดเร็วแต่ต้องแม่นยำ”

ปัจจุบันมาเลเซียมีผู้วินิจฉัยที่ผ่านการรับรองกว่า 700 คน โดยมากเป็นวิศวกรและนักกฎหมาย อย่างไรก็ตาม ในกรณีที่คู่กรณีใช้ภาษาต่างกัน ล่ามจะถูกแต่งตั้งเข้าร่วมกระบวนการเพื่อให้แน่ใจว่าการสื่อสารทุกขั้นตอนโปร่งใสและยุติธรรม

สถิติของ AIAC (2024) ระบุว่า กว่า 85% ของคำวินิจฉัยได้รับการปฏิบัติตามโดยสมัครใจ และมีเพียงไม่ถึง 2% ที่ถูกท้าทายในศาล แสดงให้เห็นถึงความเชื่อมั่นในระบบ

5. บทเรียนสำหรับประเทศไทย

5.1 บทเรียนทางกฎหมายและสถาบัน

- หากประเทศไทยต้องการออกกฎหมายลักษณะเดียวกับ CIPAA ควรพิจารณา 3 ประเด็นหลัก (TIJ, 2025):

- กำหนดขอบเขตให้ชัดเจน ว่าครอบคลุมเฉพาะการเรียกร้องเงินระหว่างโครงการ หรือรวมถึงค่าใช้จ่ายและความเสียหายภายหลังเสร็จสิ้นโครงการด้วย

- เตรียมความพร้อมของศาลและผู้พิพากษา ให้เข้าใจโครงสร้างทางเทคนิคของคดี

- สร้างหน่วยงานอิสระกลาง เพื่อบริหารจัดการและอบรมผู้วินิจฉัย

5.2 บทเรียนทางภาษาและการล่าม

ประเทศไทยควรตระหนักว่าความเข้าใจทางภาษาเป็นรากฐานของความยุติธรรมในกระบวนการนี้ จึงควร:

- จัดตั้งระบบ รับรองล่ามในกระบวนการวินิจฉัยข้อพิพาท (Certified Adjudication Interpreters)

- พัฒนาหลักสูตรอบรมล่ามด้าน “เทคนิคก่อสร้างและกฎหมายสัญญา”

- จัดทำคู่มือหลายภาษาให้ผู้ประกอบการและผู้รับเหมาขนาดกลางและเล็ก

6. การตีความ “ล่ามคือโครงสร้างพื้นฐานของความยุติธรรม”

Pöchhacker (2016) เสนอแนวคิดว่า “ล่ามคือส่วนหนึ่งของโครงสร้างการสื่อสารของสถาบัน” ไม่ใช่เพียงผู้ถ่ายทอดคำพูด หากไม่มีล่าม ความยุติธรรมในสังคมพหุภาษาย่อมไม่สามารถทำงานได้อย่างสมบูรณ์

ในบริบทของไทย การจัดตั้งระบบการวินิจฉัยข้อพิพาทภายใต้พระราชบัญญัติใหม่จึงควรดำเนินไปพร้อมกับการสร้าง มาตรฐานวิชาชีพล่ามกฎหมายและเทคนิค เช่น โครงการ “ใบรับรองผู้ล่ามด้านข้อพิพาทก่อสร้าง (CCAI)” ภายใต้ความร่วมมือของ SEAProTI, TIJ และสภาวิศวกร

7. บทสรุป

ประสบการณ์ของมาเลเซียภายใต้ CIPAA 2012 แสดงให้เห็นว่าการปฏิรูปกฎหมายที่ประสบความสำเร็จต้องอาศัยทั้ง โครงสร้างทางกฎหมาย ความเข้าใจทางเทคนิค และการสื่อสารทางภาษา ล่ามมืออาชีพเป็นหนึ่งในกลไกที่ทำให้การเข้าถึงความยุติธรรมเกิดขึ้นได้จริง

สำหรับประเทศไทย การออกกฎหมายว่าด้วยการวินิจฉัยข้อพิพาทในอุตสาหกรรมก่อสร้างควรมอง “ล่าม” เป็นส่วนหนึ่งของระบบ ไม่ใช่เพียงผู้แปลภาษา แต่คือ “ผู้พิทักษ์ความเข้าใจ” ที่ทำให้ความยุติธรรมไม่ถูกปิดกั้นด้วยภาษา

บรรณานุกรม

- AIAC. (2023). Construction Industry Payment and Adjudication Act (CIPAA) overview. Kuala Lumpur: Asian International Arbitration Centre.

- AIAC. (2024). Annual report on adjudication statistics and compliance rates. Kuala Lumpur: AIAC.

- Cheung, S., & Chong, H. (2020). Comparative adjudication regimes in Asia: Lessons for emerging economies. International Construction Law Review, 37(2), 111–136.

- Hale, S. (2021). The discourse of court interpreting: Discourse practices of the law, the witness, and the interpreter. Routledge.

- Lim, M. T. S. (2025, October 17). Experience of Malaysia in construction adjudication under CIPAA 2012. Lecture presented at the Thailand Institute of Justice (TIJ), Bangkok.

- Pöchhacker, F. (2016). Introducing interpreting studies (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Thailand Institute of Justice (TIJ). (2025). Seminar proceedings: Comparative perspectives on construction adjudication in ASEAN. Bangkok: TIJ.

- Yusoff, N. (2022). The impact of CIPAA 2012 on payment culture in the Malaysian construction industry. Asian Journal of Arbitration, 14(1), 67–88.

- Zimanyi, K. (2019). Interpreting and legitimacy in multilingual arbitration. Journal of Legal Linguistics, 12(2), 145–169.

เกี่ยวกับนักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรองของสมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้

สมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ (SEAProTI) ได้ประกาศหลักเกณฑ์และคุณสมบัติผู้ที่ขึ้นทะเบียนเป็น “นักแปลรับรอง (Certified Translators) และผู้รับรองการแปล (Translation Certification Providers) และล่ามรับรอง (Certified Interpreters)” ของสมาคม หมวดที่ 9 และหมวดที่ 10 ในราชกิจจานุเบกษา ของสำนักเลขาธิการคณะรัฐมนตรี ในสำนักนายกรัฐมนตรี แห่งราชอาณาจักรไทย ลงวันที่ 25 ก.ค. 2567 เล่มที่ 141 ตอนที่ 66 ง หน้า 100 อ่านฉบับเต็มได้ที่: นักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรอง

สำนักคณะกรรมการกฤษฎีกาเสนอให้ตราเป็นพระราชกฤษฎีกา โดยกำหนดให้นักแปลที่ขึ้นทะเบียน รวมถึงผู้รับรองการแปลจากสมาคมวิชาชีพหรือสถาบันสอนภาษาที่มีการอบรมและขึ้นทะเบียน สามารถรับรองคำแปลได้ (จดหมายถึงสมาคม SEAProTI ลงวันที่ 28 เม.ย. 2568)

สมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ เป็นสมาคมวิชาชีพแห่งแรกในประเทศไทยและภูมิภาคเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ที่มีระบบรับรองนักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรอง

สำนักงานใหญ่: อาคารบ้านราชครู เลขที่ 33 ห้อง 402 ซอยพหลโยธิน 5 ถนนพหลโยธิน แขวงพญาไท เขตพญาไท กรุงเทพมหานคร 10400 ประเทศไทย

อีเมล: hello@seaproti.com โทรศัพท์: (+66) 2-114-3128 (เวลาทำการ: วันจันทร์–วันศุกร์ เวลา 09.00–17.00 น.)