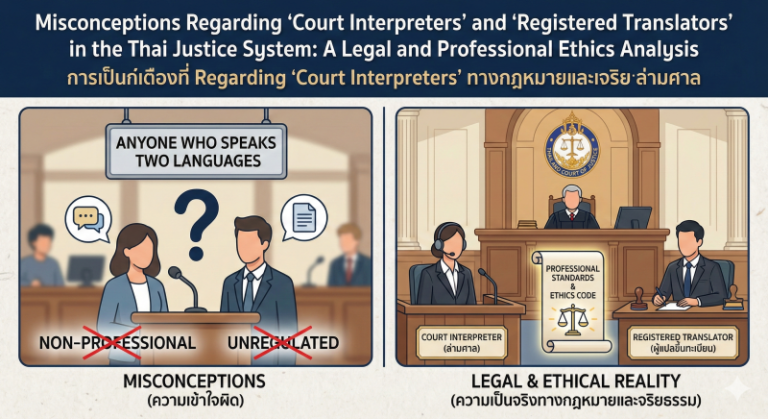

Misconceptions Regarding “Court Interpreters” and “Registered Translators” in the Thai Justice System:

A Legal and Professional Ethics Analysis

15 February 2026, Bangkok—In practice within the Thai justice system, two widespread beliefs frequently arise: (1) that in cases involving foreign suspects or defendants, only interpreters registered with the court may be used; and (2) that translated documents submitted to court must be prepared exclusively by translators registered with a government agency or the judiciary. Even though these claims are often stated in legal practice, a careful look at the laws shows that there is no specific rule that requires only certain interpreters or translators to be used.

This article analyzes the relevant legal foundations and discusses the professional and ethical implications for interpreters and translators operating within judicial proceedings.

1. Provision of Interpreters in Criminal Cases: Legal Scope

Under the ประมวลกฎหมายวิธีพิจารณาความอาญา (Criminal Procedure Code), Section 13 provides that if a defendant does not understand Thai, the court must arrange for an interpreter. However, the provision does not stipulate that the interpreter must be registered with the judiciary or certified by a specific state authority.

Key Legal Points

- The law imposes a duty on the court to provide an interpreter, not a restriction on the interpreter’s source.

- No statutory provision mandates exclusive use of court-registered interpreters.

- Courts retain discretion to assess the interpreter’s qualifications, competence, and impartiality on a case-by-case basis.

- Parties may propose or provide their interpreter, subject to disclosure before the court.

- The decisive criteria are competence and neutrality, not merely registration status.

From a human rights perspective, access to a qualified interpreter is directly linked to the right to a fair trial, a principle recognized in international legal standards (Hale, 2004; Mikkelson, 2016).

2. Status of Translated Documents in Civil and Other Proceedings

Under the ประมวลกฎหมายวิธีพิจารณาความแพ่ง (Civil Procedure Code), Section 46 does not require that translations of foreign-language documents be prepared exclusively by officially registered translators to be admissible.

- Legal and Evidentiary Considerations

- The law does not establish a monopoly qualification requirement for translators.

- Courts assess the credibility of translations based on the totality of evidence.

- If the opposing party does not challenge the accuracy of the translation, the court may accept it.

- “Certified translator” status may enhance evidentiary weight, but it is not a mandatory statutory condition.

This approach aligns with the principle of free evaluation of evidence, under which courts are not limited to specific categories of document preparers when determining probative value (Damaska, 1997).

3. Professional and Ethical Dimensions

Although the law does not impose exclusive statutory requirements, interpreters and translators remain bound by professional ethical standards, particularly in judicial contexts.

Core professional obligations include:

- Maintaining strict impartiality and independence

- Avoiding additions, omissions, or distortions of meaning

- Disclosing conflicts of interest

- Declining assignments when lacking sufficient expertise

Research shows that in court interpreting, the quality of interpretation can impact the rights of those involved, and mistakes by interpreters can harm fairness in legal processes (Berk-Seligson, 2002; Hale

Thus, while legal admissibility does not depend on registration status alone, professional accountability depends fundamentally on competence, neutrality, and ethical discipline.

4. Strategic Use of Misconceptions in Litigation

In practice, the belief that “only court-registered interpreters” or “only officially registered translators” may be used is sometimes deployed as a procedural strategy to:

- Undermine the credibility of opposing evidence

- Create procedural obstacles

- Increase bargaining leverage

However, invoking restrictions not grounded in statutory law risks distorting procedural fairness and eroding confidence in the justice system.

Professional Conclusion

Under current Thai law:

- There is no statutory requirement mandating the exclusive use of court-registered interpreters in all cases.

- There is no statutory requirement that translations be prepared solely by officially registered translators.

- Courts retain discretion to evaluate suitability and credibility on a case-by-case basis.

- The governing principles are competence, neutrality, and accuracy—not merely formal registration status.

For the translation and interpreting profession, raising standards should derive from quality assurance, ethical rigor, and professional development—not from misconceptions of legal exclusivity beyond what the law provides.

References

- Berk-Seligson, S. (2002). The bilingual courtroom: Court interpreters in the judicial process (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press.

- Damaska, M. (1997). Evidence law adrift. Yale University Press.

- Hale, S. B. (2004). The discourse of court interpreting: The discourse encompasses the practices of the law, the witness, and the interpreter. John Benjamins.

- Mikkelson, H. (2016). The book “Introduction to court interpreting” (2nd ed.) was published by Routledge in 2016. Routledge.

- ประมวลกฎหมายวิธีพิจารณาความอาญา

- ประมวลกฎหมายวิธีพิจารณาความแพ่ง

This section provides information about certified translators, translation certifiers, and certified interpreters associated with SEAProTI.

The Southeast Asian Association of Professional Translators and Interpreters (SEAProTI) has officially shared the qualifications and requirements for becoming Certified Translators, Translation Certification Providers, and Certified Interpreters in Sections 9 and 10 of the Royal Gazette, which was published by the Prime Minister’s Office in Thailand on July 25, 2024. Certified Translators, Translation Certification Providers, and Certified Interpreters

The Council of State has proposed the enactment of a Royal Decree, granting registered translators and recognised translation certifiers from professional associations or accredited language institutions the authority to provide legally valid translation certification (Letter to SEAProTI dated April 28, 2025)

SEAProTI is the first professional association in Thailand and Southeast Asia to implement a comprehensive certification system for translators, certifiers, and interpreters.

Head Office: Baan Ratchakru Building, No. 33, Room 402, Soi Phahonyothin 5, Phahonyothin Road, Phaya Thai District, Bangkok 10400, Thailand

Email: hello@seaproti.com | Tel.: (+66) 2-114-3128 (Office hours: Mon–Fri, 09:00–17:00)

ความเข้าใจผิดเกี่ยวกับ “ล่ามศาล” และ “นักแปลขึ้นทะเบียน” ในกระบวนการยุติธรรมไทย:

การวิเคราะห์เชิงกฎหมายและจริยธรรมวิชาชีพ

15 กุมภาพันธ์ 2569, กรุงเทพมหานคร – ในทางปฏิบัติของกระบวนการยุติธรรมไทย มักปรากฏความเชื่อแพร่หลายสองประการ ได้แก่ (1) คดีที่มีผู้ต้องหา/จำเลยเป็นชาวต่างชาติจะต้องใช้ล่ามที่ขึ้นทะเบียนกับศาลเท่านั้น และ (2) เอกสารแปลที่จะใช้ในศาลต้องจัดทำโดยนักแปลที่ขึ้นทะเบียนกับหน่วยงานของรัฐหรือศาลยุติธรรมเท่านั้น ความเข้าใจดังกล่าว แม้จะถูกอ้างซ้ำในทางปฏิบัติ แต่เมื่อพิจารณาตามตัวบทกฎหมาย กลับไม่ปรากฏบทบัญญัติที่กำหนดเงื่อนไขเชิงผูกขาดเช่นนั้นโดยชัดแจ้ง

บทความนี้มุ่งวิเคราะห์ฐานกฎหมายที่เกี่ยวข้อง พร้อมอภิปรายผลกระทบเชิงวิชาชีพและจริยธรรมต่อบทบาทของล่ามและนักแปลในกระบวนการยุติธรรม

1. การจัดหาล่ามในคดีอาญา: ขอบเขตตามกฎหมาย

ภายใต้ ประมวลกฎหมายวิธีพิจารณาความอาญา มาตรา 13 กำหนดว่า หากจำเลยไม่เข้าใจภาษาไทย ศาลต้องจัดให้มีล่าม อย่างไรก็ตาม บทบัญญัติดังกล่าวไม่ได้ระบุว่าล่ามต้องเป็นผู้ที่ขึ้นทะเบียนกับศาลหรือผ่านการอบรมจากหน่วยงานของรัฐเท่านั้น

ประเด็นเชิงกฎหมายที่ควรทำความเข้าใจ

- กฎหมายกำหนด “หน้าที่ของศาลในการจัดให้มีล่าม” มิใช่ “ข้อจำกัดแหล่งที่มาของล่าม”

- ไม่มีบทบัญญัติที่บัญญัติให้ต้องใช้เฉพาะล่ามขึ้นทะเบียนกับศาลยุติธรรม

- ศาลมีดุลพินิจพิจารณาคุณสมบัติ ความสามารถ และความเป็นกลางของล่ามเป็นรายกรณี

- คู่ความสามารถเสนอหรือจัดหาล่ามของตนเองได้ โดยต้องแถลงต่อศาล

หลักสำคัญอยู่ที่ความสามารถ (competence) และความเป็นกลาง (neutrality) มิใช่สถานะการขึ้นทะเบียนเพียงอย่างเดียว

ในเชิงสิทธิมนุษยชน การมีล่ามที่มีคุณภาพสัมพันธ์โดยตรงกับหลักการพิจารณาคดีอย่างเป็นธรรม (fair trial) ซึ่งเป็นหลักสากล (Hale, 2004; Mikkelson, 2016)

2. สถานะของเอกสารแปลในคดีแพ่งและคดีอื่น

ภายใต้ ประมวลกฎหมายวิธีพิจารณาความแพ่ง มาตรา 46 กฎหมายมิได้กำหนดว่าคำแปลเอกสารภาษาต่างประเทศจะต้องจัดทำโดยนักแปลที่ขึ้นทะเบียนกับศาลหรือหน่วยงานราชการเท่านั้นจึงจะรับฟังได้

- ประเด็นเชิงกฎหมายและพยานหลักฐาน

- กฎหมายไม่ได้กำหนด “คุณสมบัติผูกขาด” ของผู้แปล

- ศาลพิจารณาความน่าเชื่อถือของคำแปลตามพยานหลักฐานโดยรวม

- หากคู่ความฝ่ายตรงข้ามไม่โต้แย้งความถูกต้องของคำแปล ศาลอาจรับฟังได้

- สถานะ “นักแปลรับรอง” อาจเพิ่มน้ำหนักความน่าเชื่อถือ แต่ไม่ใช่เงื่อนไขบังคับทางกฎหมาย

หลักการดังกล่าวสอดคล้องกับแนวคิดเรื่องการประเมินพยานหลักฐานตามดุลพินิจของศาล (free evaluation of evidence) ซึ่งมิได้จำกัดเฉพาะแหล่งที่มาของผู้จัดทำเอกสาร (Damaska, 1997)

3. มิติทางจริยธรรมและวิชาชีพ

แม้กฎหมายจะมิได้กำหนดข้อบังคับเชิงผูกขาด แต่ในทางวิชาชีพ ล่ามและนักแปลควรยึดถือมาตรฐานจริยธรรมอย่างเคร่งครัด โดยเฉพาะในด้าน:

- ความเป็นกลางและไม่ฝักใฝ่ฝ่ายใด

- การไม่เพิ่ม ลด หรือบิดเบือนสาระสำคัญ

- การเปิดเผยความขัดแย้งทางผลประโยชน์ (conflict of interest)

- การปฏิเสธงานเมื่อขาดความเชี่ยวชาญเพียงพอ

งานศึกษาทางวิชาการด้านล่ามศาลชี้ชัดว่า “คุณภาพของการสื่อความหมาย” มีผลต่อสิทธิของคู่ความโดยตรง และความผิดพลาดของล่ามอาจกระทบต่อความชอบด้วยกระบวนพิจารณา (Berk-Seligson, 2002; Hale, 2004)

4. การใช้ความเข้าใจผิดเป็นยุทธศาสตร์ทางคดี

ในทางปฏิบัติ ความเชื่อว่า “ต้องใช้ล่ามศาลเท่านั้น” หรือ “ต้องใช้นักแปลขึ้นทะเบียนเท่านั้น” บางครั้งถูกนำมาใช้เป็นกลยุทธ์ทางกระบวนพิจารณา เพื่อ:

- ลดทอนความน่าเชื่อถือของพยานหลักฐานฝ่ายตรงข้าม

- สร้างอุปสรรคเชิงขั้นตอน

- เพิ่มอำนาจต่อรอง

อย่างไรก็ตาม การอ้างข้อจำกัดที่ไม่มีฐานกฎหมายรองรับ อาจนำไปสู่ความเข้าใจคลาดเคลื่อนในระบบ และกระทบต่อความไว้วางใจในกระบวนการยุติธรรมโดยรวม

บทสรุปเชิงวิชาชีพ

ข้อเท็จจริงตามกฎหมายไทยในปัจจุบันสามารถสรุปได้ดังนี้

- ไม่มีกฎหมายกำหนดให้ต้องใช้เฉพาะล่ามที่ขึ้นทะเบียนกับศาลในทุกกรณี

- ไม่มีกฎหมายกำหนดให้เอกสารแปลต้องจัดทำโดยนักแปลขึ้นทะเบียนเท่านั้น

- ศาลมีดุลพินิจประเมินความเหมาะสมและความน่าเชื่อถือเป็นรายกรณี

- หลักสำคัญคือความสามารถ ความเป็นกลาง และความถูกต้อง ไม่ใช่เพียงสถานะทางทะเบียน

สำหรับวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่าม การยกระดับมาตรฐานควรเกิดจากการพัฒนาคุณภาพและจริยธรรม มิใช่การสร้างความเข้าใจผูกขาดที่เกินกว่าที่กฎหมายบัญญัติไว้

References

- Berk-Seligson, S. (2002). The bilingual courtroom: Court interpreters in the judicial process (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press.

- Damaska, M. (1997). Evidence law adrift. Yale University Press.

- Hale, S. B. (2004). The discourse of court interpreting: Discourse practices of the law, the witness, and the interpreter. John Benjamins.

- Mikkelson, H. (2016). Introduction to court interpreting (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- ประมวลกฎหมายวิธีพิจารณาความอาญา

- ประมวลกฎหมายวิธีพิจารณาความแพ่ง

สมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ (SEAProTI) ได้ประกาศหลักเกณฑ์และคุณสมบัติของผู้ที่ขึ้นทะเบียนเป็น “นักแปลรับรอง (Certified Translators) และผู้รับรองการแปล (Translation Certification Providers) และล่ามรับรอง (Certified Interpreters)” ของสมาคม หมวดที่ 9 และหมวดที่ 10 ในราชกิจจานุเบกษา ของสำนักเลขาธิการคณะรัฐมนตรี ในสำนักนายกรัฐมนตรี แห่งราชอาณาจักรไทย ลงวันที่ 25 ก.ค. 2567 เล่มที่ 141 ตอนที่ 66 ง หน้า 100 อ่านฉบับเต็มได้ที่: นักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรอง

สำนักคณะกรรมการกฤษฎีกาเสนอให้ตราเป็นพระราชกฤษฎีกา โดยกำหนดให้นักแปลที่ขึ้นทะเบียน รวมถึงผู้รับรองการแปลจากสมาคมวิชาชีพหรือสถาบันสอนภาษาที่มีการอบรมและขึ้นทะเบียน สามารถรับรองคำแปลได้ (จดหมายถึงสมาคม SEAProTI ลงวันที่ 28 เม.ย. 2568)

สมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้เป็นสมาคมวิชาชีพแห่งแรกและแห่งเดียวในประเทศไทยและภูมิภาคเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ที่มีระบบรับรองนักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรอง

สำนักงานใหญ่: อาคารบ้านราชครู เลขที่ 33 ห้อง 402 ซอยพหลโยธิน 5 ถนนพหลโยธิน แขวงพญาไท เขตพญาไท กรุงเทพมหานคร 10400 ประเทศไทย

อีเมล: hello@seaproti.com โทรศัพท์: (+66) 2-114-3128 (เวลาทำการ: วันจันทร์–วันศุกร์ เวลา 09.00–17.00 น.