Interpretation of Section 13 of the Criminal Procedure Code:

The Status of “Court-Registered Interpreters” and the Safeguarding of the Accused’s Right to a Fair Trial

15 February 2026, Bangkok – This article analyzes the interpretation of Section 13 of the Criminal Procedure Code concerning the provision of interpreters for defendants who do not understand the Thai language. It looks into whether the law says that interpreters must be officially registered with the Court of Justice. Based on Supreme Court decisions, Section 13 mainly aims to protect the accused’s right to understand the legal process and defend themselves, rather than strictly requiring interpreters to be officially registered. The Court therefore retains discretion to assess the qualifications and suitability of interpreters on a case-by-case basis. Nevertheless, where interpretation deficiencies significantly impair the defendant’s right of defense, the proceedings may be rendered defective.

Keywords: court interpreters, Section 13 Criminal Procedure Code, defendants’ rights, fair trial, judicial discretion

The Right to a Fair Trial and Linguistic Assistance

The right to a fair trial constitutes a fundamental principle of criminal justice. A core component of this right is the defendant’s ability to understand both the charges and the proceedings in a meaningful and effective manner. In Thailand, Section 13 of the Criminal Procedure Code provides that where a defendant does not understand the Thai language, the court must arrange for an interpreter.

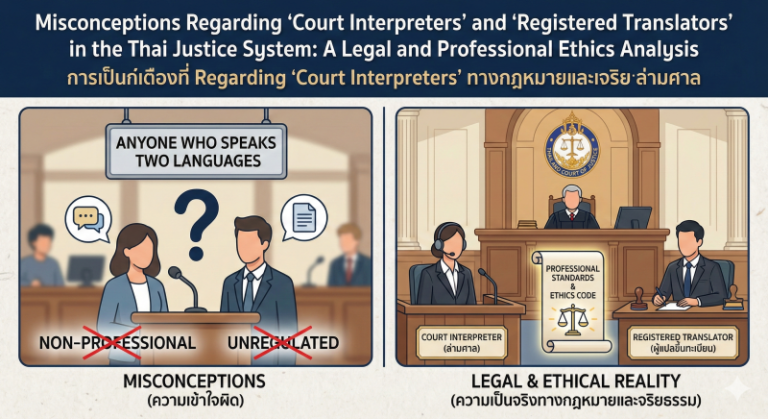

In practice, however, a recurring issue arises: must the interpreter necessarily be a person formally registered with the Thai Courts of Justice? This article examines Supreme Court reasoning and procedural principles in order to clarify the legislative intent of Section 13 and the scope of judicial discretion.

Legal Framework under Section 13 of the Criminal Procedure Code

Section 13 provides that if a defendant cannot understand Thai, the court shall arrange for an interpreter to ensure comprehension throughout the proceedings. This provision operates as a fundamental procedural safeguard rather than a purely technical rule.

A textual interpretation of the statute reveals that the interpreter is not explicitly required to be drawn exclusively from the official registry maintained by the Courts of Justice. The essence of the provision, therefore, lies in the interpreter’s competence, neutrality, and effectiveness, rather than in formal registration status.

Supreme Court Jurisprudence and Judicial Discretion

Supreme Court jurisprudence has established that Section 13 is a flexible formal requirement. If the facts show that the defendant knew the charges and could defend themselves properly, not having a registered interpreter doesn’t automatically make the case invalid.

Accordingly, courts retain discretion to evaluate interpreter qualifications on a case-by-case basis, taking into account:

- Linguistic competence

- Neutrality and reliability

- Accuracy and completeness in conveying substantive content

This approach reflects the broader procedural principle of substance over form in criminal adjudication.

The Court Interpreter Registry: A Professional Standard, Not a Legal Condition

In practice, the Thai Courts of Justice maintain a registry of court interpreters to facilitate case management and promote professional standards. While this system serves important administrative and quality-assurance functions, it does not constitute an absolute legal prerequisite for validity.

In other words, the failure to appoint an interpreter from the official registry does not, by itself, render the proceedings void provided that the defendant genuinely understood the essential substance of the case and was able to exercise procedural rights effectively.

However, if an interpreter is not skilled enough or if mistakes in translation seriously impact the defendant’s ability to defend themselves, these issues could compromise the fairness of the proceedings and might make them invalid.

Comparative and International Perspective

The protection of linguistic assistance rights is not unique to Thai law. It shows that there are global standards, like those in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which ensure that anyone accused of a crime has the right to a free interpreter if they don’t understand the language used in court (United Nations, 1966).

So, the way we understand Section 13 should focus on protecting basic rights instead of strictly following rules about how interpreters are registered.

Conclusion

Section 13 of the Criminal Procedure Code is designed primarily to safeguard the defendant’s right to understand and defend against criminal charges. It does not impose a fixed or mandatory requirement that interpreters must be formally registered with the Courts of Justice. Courts are empowered to decide whether an interpreter is qualified and appropriate based on their competence, neutrality, and the actual effect on the defendant’s rights.

While the use of registered court interpreters represents good practice and supports professional standards, it is not an absolute condition for legal validity. When the court adequately safeguards the defendant’s right to understanding and defense, the proceedings remain legal and equitable.

References

- Criminal Procedure Code (Thailand), Section 13.

- United Nations. (1966). International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. https://www.ohchr.org

- Supreme Court of Thailand. (1986). The Supreme Court of Thailand rendered judgments regarding the interpretation of Section 13 of the Criminal Procedure Code.

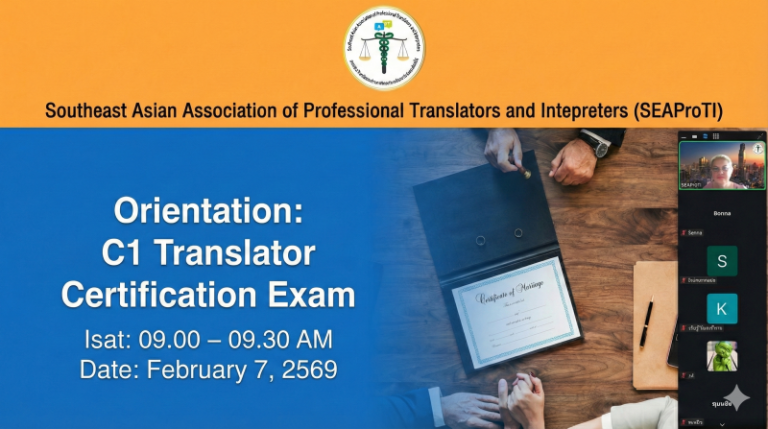

This section provides information about Certified Translators, Translation Certifiers, and Certified Interpreters associated with SEAProTI.

The Southeast Asian Association of Professional Translators and Interpreters (SEAProTI) has officially shared the qualifications and requirements for becoming Certified Translators, Translation Certification Providers, and Certified Interpreters in Sections 9 and 10 of the Royal Gazette, which was published by the Prime Minister’s Office in Thailand on July 25, 2024. Certified Translators, Translation Certification Providers, and Certified Interpreters

The Council of State has proposed the enactment of a Royal Decree, granting registered translators and recognised translation certifiers from professional associations or accredited language institutions the authority to provide legally valid translation certification (Letter to SEAProTI dated April 28, 2025)

SEAProTI is the first professional association in Thailand and Southeast Asia to implement a comprehensive certification system for translators, certifiers, and interpreters.

Head Office: Baan Ratchakru Building, No. 33, Room 402, Soi Phahonyothin 5, Phahonyothin Road, Phaya Thai District, Bangkok 10400, Thailand

Email: hello@seaproti.com | Tel.: (+66) 2-114-3128 (Office hours: Mon–Fri, 09:00–17:00)

การตีความมาตรา 13 แห่งประมวลกฎหมายวิธีพิจารณาความอาญา: สถานะ “ล่ามขึ้นทะเบียนศาล” กับหลักประกันสิทธิในการต่อสู้คดีของจำเลย

15 กุมภาพันธ์ 2569, กรุงเทพมหานคร—บทความนี้วิเคราะห์การตีความมาตรา 13 แห่งประมวลกฎหมายวิธีพิจารณาความอาญาเกี่ยวกับการจัดหาล่ามให้จำเลยที่ไม่เข้าใจภาษาไทย โดยมุ่งพิจารณาว่ากฎหมายกำหนดให้ต้องใช้ล่ามที่ขึ้นทะเบียนกับศาลยุติธรรมหรือไม่ จากแนววินิจฉัยของศาลฎีกา พบว่า บทบัญญัติดังกล่าวมุ่งคุ้มครอง “สิทธิในการเข้าใจและต่อสู้คดี” มากกว่าการกำหนดรูปแบบเชิงทะเบียนของล่ามเป็นการตายตัว ศาลจึงมีดุลพินิจพิจารณาคุณสมบัติและความเหมาะสมของล่ามเป็นรายกรณี อย่างไรก็ดี หากการแปลบกพร่องจนกระทบสิทธิของจำเลยอย่างมีนัยสำคัญ ย่อมเป็นเหตุให้กระบวนพิจารณาเสียไปได้

คำสำคัญ: ล่ามศาล, มาตรา 13 ป.วิ.อ., สิทธิจำเลย, ความเป็นธรรมในกระบวนพิจารณา, ดุลพินิจศาล

สิทธิในการได้รับการพิจารณาคดีอย่างเป็นธรรม (fair trial) เป็นหลักการพื้นฐานของกระบวนการยุติธรรมทางอาญา หนึ่งในองค์ประกอบสำคัญของสิทธิดังกล่าวคือ สิทธิของจำเลยที่จะเข้าใจข้อกล่าวหาและกระบวนการพิจารณาคดีอย่างแท้จริง ในบริบทของประเทศไทย มาตรา 13 แห่งประมวลกฎหมายวิธีพิจารณาความอาญา (ป.วิ.อ.) บัญญัติให้ศาลต้องจัดให้มีล่ามเมื่อจำเลยไม่เข้าใจภาษาไทย

อย่างไรก็ตาม ประเด็นที่เกิดขึ้นในทางปฏิบัติคือ ล่ามดังกล่าวจำเป็นต้องเป็น “ล่ามที่ขึ้นทะเบียนกับศาลยุติธรรม” เท่านั้นหรือไม่ บทความนี้มุ่งวิเคราะห์แนววินิจฉัยของศาลฎีกาและหลักการเชิงกระบวนวิธี เพื่อทำความเข้าใจเจตนารมณ์ของบทบัญญัติและขอบเขตของดุลพินิจศาล

กรอบกฎหมายตามมาตรา 13 ป.วิ.อ.

มาตรา 13 ป.วิ.อ. บัญญัติว่า หากจำเลยไม่สามารถเข้าใจภาษาไทย ศาลต้องจัดให้มีล่ามแปลให้เข้าใจได้ตลอดกระบวนพิจารณา บทบัญญัตินี้มีลักษณะเป็นหลักประกันสิทธิขั้นพื้นฐาน มิใช่เพียงข้อกำหนดทางเทคนิคของกระบวนการ

เมื่อพิจารณาถ้อยคำของกฎหมาย จะพบว่า มิได้มีข้อความใดกำหนดโดยชัดแจ้งว่า “ล่ามต้องเป็นผู้ขึ้นทะเบียนกับศาลยุติธรรมเท่านั้น” การตีความตามตัวบทจึงสะท้อนว่า สาระสำคัญอยู่ที่ “ความสามารถในการทำหน้าที่อย่างถูกต้องและเป็นกลาง” มากกว่าสถานะเชิงทะเบียน

แนววินิจฉัยของศาลฎีกาและหลักดุลพินิจ

แนวคำพิพากษาศาลฎีกาได้วางหลักว่า บทบัญญัติมาตรา 13 มิได้เป็นบทบังคับเด็ดขาดในเชิงรูปแบบ หากข้อเท็จจริงปรากฏว่าจำเลยเข้าใจข้อกล่าวหาและสามารถใช้สิทธิในการต่อสู้คดีได้อย่างครบถ้วน แม้มิได้ใช้ล่ามที่ขึ้นทะเบียน ก็ไม่ทำให้กระบวนพิจารณาเป็นโมฆะโดยอัตโนมัติ

ศาลจึงมีดุลพินิจในการพิจารณาคุณสมบัติของล่ามเป็นรายกรณี โดยพิจารณาจาก

- ความสามารถทางภาษา

- ความเป็นกลางและความน่าเชื่อถือ

- ความครบถ้วนและถูกต้องของการถ่ายทอดสาระสำคัญ

แนวคิดดังกล่าวสอดคล้องกับหลัก “สาระสำคัญเหนือรูปแบบ” (substance over form) ในกระบวนพิจารณาคดีอาญา

ระบบบัญชีรายชื่อล่ามศาล: บทบาทเชิงมาตรฐาน มิใช่เงื่อนไขความชอบด้วยกฎหมาย

ในทางปฏิบัติ ศาลยุติธรรมมีระบบบัญชีรายชื่อล่าม (registered court interpreters) เพื่ออำนวยความสะดวกและสร้างมาตรฐานวิชาชีพ ระบบดังกล่าวมีคุณค่าเชิงบริหารจัดการและส่งเสริมคุณภาพ แต่ไม่ใช่เงื่อนไขความชอบด้วยกฎหมายโดยเด็ดขาด

กล่าวอีกนัยหนึ่ง การไม่ใช้ล่ามในบัญชีรายชื่อ มิได้ทำให้กระบวนพิจารณาเป็นโมฆะ หากปรากฏว่าจำเลยเข้าใจสาระสำคัญและสิทธิของตนอย่างแท้จริง

อย่างไรก็ตาม หากปรากฏว่าล่ามขาดความสามารถ หรือการแปลคลาดเคลื่อนอย่างมีนัยสำคัญจนกระทบสิทธิในการต่อสู้คดี ย่อมอาจเป็นเหตุให้กระบวนพิจารณาเสียไป เนื่องจากกระทบต่อหลักความเป็นธรรม

การคุ้มครองสิทธิจำเลยในมิติเปรียบเทียบ

หลักการคุ้มครองสิทธิในการได้รับความช่วยเหลือด้านภาษา มิได้จำกัดเฉพาะกฎหมายไทย แต่เป็นมาตรฐานสากลที่รับรองในกติการะหว่างประเทศ เช่น กติการะหว่างประเทศว่าด้วยสิทธิพลเมืองและสิทธิทางการเมือง (ICCPR) ซึ่งกำหนดให้บุคคลมีสิทธิได้รับความช่วยเหลือจากล่ามโดยไม่เสียค่าใช้จ่าย หากไม่เข้าใจภาษาที่ใช้ในศาล (United Nations, 1966)

ดังนั้น การตีความมาตรา 13 จึงควรตั้งอยู่บนฐานของหลักประกันสิทธิขั้นพื้นฐาน มิใช่เน้นเพียงรูปแบบทางทะเบียน

บทสรุป

มาตรา 13 แห่งประมวลกฎหมายวิธีพิจารณาความอาญามุ่งคุ้มครอง “สิทธิในการเข้าใจและต่อสู้คดี” ของจำเลยเป็นสำคัญ มิได้กำหนดรูปแบบตายตัวเกี่ยวกับสถานะทางทะเบียนของล่าม ศาลมีดุลพินิจพิจารณาคุณสมบัติและความเหมาะสมของล่ามเป็นรายกรณี โดยพิจารณาจากความสามารถ ความเป็นกลาง และผลกระทบต่อสิทธิของจำเลย

การใช้ล่ามที่ขึ้นทะเบียนกับศาลยุติธรรมเป็นแนวปฏิบัติที่ดีและส่งเสริมมาตรฐานวิชาชีพ แต่ไม่ใช่เงื่อนไขบังคับเด็ดขาดของความชอบด้วยกฎหมาย หากสาระสำคัญของสิทธิในการรับรู้และต่อสู้คดีได้รับการคุ้มครองอย่างแท้จริง กระบวนพิจารณาย่อมยังคงความชอบด้วยกฎหมายและความเป็นธรรม

เอกสารอ้างอิง

- ประมวลกฎหมายวิธีพิจารณาความอาญา มาตรา 13.

- United Nations. (1966). International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. https://www.ohchr.org

- ศาลฎีกา. (2529). คำพิพากษาศาลฎีกาที่เกี่ยวข้องกับการตีความมาตรา 13 แห่งประมวลกฎหมายวิธีพิจารณาความอา.

สำนักคณะกรรมการกฤษฎีกาเสนอให้ตราเป็นพระราชกฤษฎีกา โดยกำหนดให้นักแปลที่ขึ้นทะเบียน รวมถึงผู้รับรองการแปลจากสมาคมวิชาชีพหรือสถาบันสอนภาษาที่มีการอบรมและขึ้นทะเบียน สามารถรับรองคำแปลได้ (จดหมายถึงสมาคม SEAProTI ลงวันที่ 28 เม.ย. 2568)

สมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้เป็นสมาคมวิชาชีพแห่งแรกและแห่งเดียวในประเทศไทยและภูมิภาคเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ที่มีระบบรับรองนักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรอง

สำนักงานใหญ่: อาคารบ้านราชครู เลขที่ 33 ห้อง 402 ซอยพหลโยธิน 5 ถนนพหลโยธิน แขวงพญาไท เขตพญาไท กรุงเทพมหานคร 10400 ประเทศไทย

อีเมล: hello@seaproti.com โทรศัพท์: (+66) 2-114-3128 (เวลาทำการ: วันจันทร์–วันศุกร์ เวลา 09.00–17.00 น.