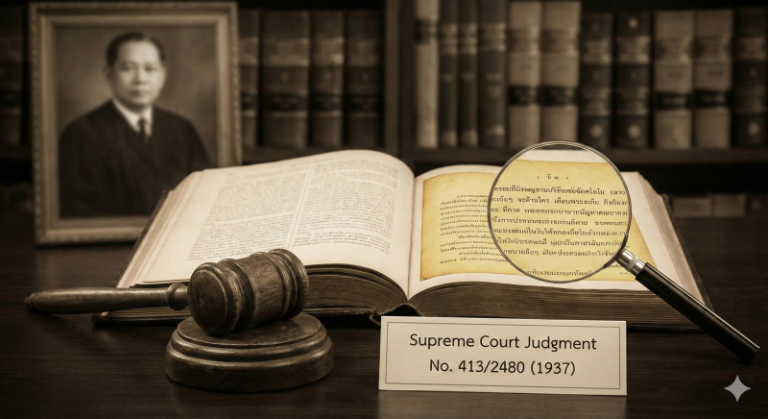

A Forensic Linguistic Analysis of Supreme Court Judgment No. 413/2480

Author: Wanitcha Sumanas, President, Southeast Asian Association of Professional Translators and Interpreters (SEAProTI)

Forensic Linguist

18 February 2026, Bangkok—Supreme Court Judgment No. 413/2480 constitutes an important case study illustrating the relationship between “language” and the “elements of criminal liability,” particularly in relation to defamation of a public official under Section 339 of the Thai Penal Code and allegations concerning the defamation of the appointing authority.

The central issue in the case concerns whether the defendant’s words made a specific reference to an identifiable individual and whether the communicative intent extended to the minister who appointed the district education officer.

This analysis applies a forensic linguistics framework to examine:

(1) referential identification,

(2) communicative intent, and

(3) the pragmatic scope of the disputed utterance.

Facts of the Case (Brief Overview)

The prosecution alleged that the defendant made insulting remarks about a “district education officer” and disparaged “the person who appointed him,” using vulgar language that allegedly caused public contempt toward the appointing authority, who at the time served as Minister of Education.

The Court of First Instance held that the defendant was guilty of defaming both the public official and the appointing authority.

However, the Supreme Court ruled that:

The defendant did not know the identity of the appointing authority, and the prosecution failed to prove that the defendant intended to defame that particular individual. It would therefore be improper to interpret a broad expression as imputing defamation against a specific person.

Accordingly, the Court upheld liability only under Section 339(2) for defaming the district education officer.

3. Forensic Linguistic Analysis

3.1 Referential Ambiguity

In forensic linguistics, a key requirement in defamation cases is identifiability—that the allegedly defamatory statement must clearly identify, or be reasonably understood to identify, a specific individual.

The disputed statement was:

“The one who appointed him didn’t care or supervise properly—appointing such a worthless person as district education officer.”

This expression constitutes a functional reference, rather than a direct naming of an individual. There was no evidence that the defendant knew who the appointing authority was.

Linguistically, the statement demonstrates:

- A non-specific referent

- A lack of a definite identifier

The Supreme Court therefore concluded that extending the phrase “the one who appointed him” to a specific minister, without evidentiary support, exceeded the semantic and evidentiary boundaries of the utterance.

3.2 Communicative Intent

A fundamental element in defamation is mens rea (criminal intent).

The Supreme Court emphasized that:

- The defendant did not know the identity of the appointing authority.

- The prosecution failed to prove that the defendant specifically intended to defame that individual.

From a forensic linguistic perspective, this distinction separates:

- Emotional expression, and

- Targeted defamation intent.

The defendant’s language appears to reflect:

- Emotional outburst,

- Direct insult toward the officeholder (district education officer),

- No demonstrable intent directed at the appointing authority.

- The Court thus limited criminal liability to the directly referenced individual.

3.3 Pragmatic Scope

In pragmatics, meaning is not derived solely from words themselves, but from context.

However, legal interpretation is governed by the principle of legal certainty, particularly in criminal law.

The Supreme Court rejected an expansive interpretation linking the phrase “the one who appointed him” automatically to the minister because:

- No name was mentioned.

- No evidence showed that listeners understood the phrase to refer to that specific individual.

- No evidence proved that the defendant knew the appointing authority’s identity.

This reasoning reflects a core principle of criminal law:

Criminal provisions must be interpreted strictly, and liability cannot be expanded beyond proven elements.

4. Burden of Proof

The judgment reinforces the burden of proof in criminal proceedings. The prosecution must establish that:

- The defendant knew the identity of the alleged victim.

- The statement was sufficient to identify that person.

- The defendant intended to defame that individual.

Where such proof is lacking, the benefit of the doubt must be given to the defendant.

5. Theoretical and Academic Significance

This judgment is significant in at least three respects:

- It affirms the identifiability principle in defamation law.

- It restricts the expansion of general expressions to specific individuals without evidence.

- It reflects an implicit application of linguistic reasoning, even before forensic linguistics was formally recognized as a discipline.

The reasoning aligns with Shuy’s (1993) view that legal evaluation of speech must distinguish between the actual linguistic evidence and speculative interpretation advanced by the accuser.

6. Conclusion

Supreme Court Judgment No. 413/2480 demonstrates that criminal defamation requires:

- Clear identification of the alleged victim, and

- Provable intent directed toward that person.

- Broad or generalized language cannot automatically be extended to impose liability on a specific individual.

The decision underscores the principle of legal certainty in criminal law and aligns closely with foundational principles in forensic linguistic analysis.

References

- Coulthard, M., Johnson, A., & Wright, D. (2017). An introduction to forensic linguistics: Language in evidence (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Shuy, R. W. (1993). Language crimes: The use and abuse of language evidence in the courtroom. Blackwell.

- Tiersma, P. M. (1999). Legal language. University of Chicago Press.

- Thai Penal Code. (n.d.).

- Supreme Court Judgment No. 413/2480. Assistant Judges Division of the Supreme Court of Thailand.

This section provides information about certified translators, translation certifiers, and certified interpreters associated with SEAProTI.

The Southeast Asian Association of Professional Translators and Interpreters (SEAProTI) has officially shared the qualifications and requirements for becoming Certified Translators, Translation Certification Providers, and Certified Interpreters in Sections 9 and 10 of the Royal Gazette, which was published by the Prime Minister’s Office in Thailand on July 25, 2024. Certified Translators, Translation Certification Providers, and Certified Interpreters

The Council of State has proposed the enactment of a Royal Decree, granting registered translators and recognised translation certifiers from professional associations or accredited language institutions the authority to provide legally valid translation certification (Letter to SEAProTI dated April 28, 2025)

SEAProTI is the first professional association in Thailand and Southeast Asia to implement a comprehensive certification system for translators, certifiers, and interpreters.

Head Office: Baan Ratchakru Building, No. 33, Room 402, Soi Phahonyothin 5, Phahonyothin Road, Phaya Thai District, Bangkok 10400, Thailand

Email: hello@seaproti.com | Tel.: (+66) 2-114-3128 (Office hours: Mon–Fri, 09:00–17:00)

การวิเคราะห์คำพิพากษาศาลฎีกาที่ 413/2480 ด้วยกรอบนิติภาษาศาสตร์ (Forensic Linguistics)

ผู้เขียน วณิชชา สุมานัส นายกสมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ และนักนิติภาษาศาสตร์

18 กุมภาพันธ์ 2569, กรุงเทพมหานคร – คำพิพากษาศาลฎีกาที่ 413/2480 เป็นกรณีศึกษาสำคัญที่สะท้อนความสัมพันธ์ระหว่าง “ถ้อยคำ” กับ “องค์ประกอบความผิดทางอาญา” โดยเฉพาะความผิดฐานหมิ่นประมาทเจ้าพนักงานตามประมวลกฎหมายอาญา มาตรา 339 และข้อกล่าวหาเกี่ยวกับการหมิ่นประมาทผู้แต่งตั้งเจ้าพนักงาน

ประเด็นสำคัญของคดีอยู่ที่การตีความว่า ถ้อยคำที่จำเลยกล่าวมีลักษณะ “พาดพิงเฉพาะเจาะจง” (specific reference) ต่อบุคคลใดบุคคลหนึ่งหรือไม่ และเจตนาทางภาษาของผู้พูดครอบคลุมถึงบุคคลระดับรัฐมนตรีผู้แต่งตั้งหรือไม่

การวิเคราะห์นี้ใช้กรอบนิติภาษาศาสตร์ (forensic linguistics) เพื่อพิจารณา (1) การระบุตัวบุคคลในถ้อยคำ (referential identification) (2) เจตนาทางสื่อสาร (communicative intent) และ (3) ขอบเขตของความหมายเชิงปฏิบัติการ (pragmatic scope) ของข้อความที่เป็นข้อพิพาท

ข้อเท็จจริงโดยสังเขป

โจทก์ฟ้องว่า จำเลยกล่าวถ้อยคำดูหมิ่น “ธรรมการอำเภอ” และกล่าวพาดพิงถึง “ผู้ตั้ง” โดยมีลักษณะหยาบคาย และทำให้ประชาชนดูหมิ่นผู้แต่งตั้ง ซึ่งขณะนั้นดำรงตำแหน่งเสนาบดีกระทรวงธรรมการ

ศาลชั้นต้นเห็นว่าจำเลยมีความผิดทั้งฐานหมิ่นประมาทเจ้าพนักงาน และหมิ่นประมาทผู้แต่งตั้ง

อย่างไรก็ตาม ศาลฎีกาวินิจฉัยว่า:

- จำเลยไม่รู้ตัวผู้ตั้ง และโจทก์ไม่นำสืบว่าจำเลยมีเจตนาหมิ่นประมาทบุคคลนั้นโดยเฉพาะ การตีความถ้อยคำกว้าง ๆ ไปผูกกับบุคคลเฉพาะรายจึงไม่ชอบ

- จึงลงโทษเฉพาะฐานหมิ่นประมาทธรรมการอำเภอตามมาตรา 339(2)

3. การวิเคราะห์เชิงนิติภาษาศาสตร์

3.1 ปัญหาการอ้างอิงบุคคล (Referential Ambiguity)

ในนิติภาษาศาสตร์ การจะถือว่าถ้อยคำเป็นการหมิ่นประมาท ต้องปรากฏองค์ประกอบสำคัญคือ “การระบุตัวบุคคลที่ถูกกล่าวถึงอย่างชัดเจนหรือสามารถระบุได้” (identifiability principle)

ถ้อยคำว่า:

“ผู้ตั้งมาก็ไม่ดูไม่แล ตั้งคนหมา ๆ มาเป็นธรรมการอำเภอ”

มีลักษณะเป็นการอ้างอิงเชิงหน้าที่ (functional reference) ไม่ใช่การระบุชื่อบุคคลโดยตรง และไม่มีพยานหลักฐานว่าจำเลยรู้ว่าใครเป็นผู้แต่งตั้ง

ในเชิงภาษาศาสตร์ ถ้อยคำดังกล่าวเป็น:

- การอ้างอิงแบบไม่เฉพาะเจาะจง (non-specific referent)

- ขาดตัวบ่งชี้ชัดเจน (lack of definite identifier)

ศาลฎีกาจึงตีความว่า การขยายความหมายจากคำว่า “ผู้ตั้ง” ไปยังบุคคลเฉพาะรายโดยไม่มีพยานหลักฐานสนับสนุน เป็นการขยายความเกินกว่าขอบเขตของถ้อยคำ

3.2 เจตนาเชิงสื่อสาร (Communicative Intent)

หลักสำคัญในคดีหมิ่นประมาทคือ “เจตนา” (mens rea)

จากคำพิพากษา ศาลฎีกาให้ความสำคัญกับ:

- จำเลยไม่รู้จักตัวผู้ตั้ง

- โจทก์ไม่นำสืบว่า จำเลยมุ่งหมายถึงบุคคลใดโดยเฉพาะ

- ในกรอบนิติภาษาศาสตร์ นี่คือการแยก “เจตนาเชิงอารมณ์” (emotional expression) ออกจาก “เจตนาเชิงมุ่งหมายเฉพาะบุคคล” (targeted defamation intent)

ถ้อยคำของจำเลยมีลักษณะเป็น:

- การระบายอารมณ์

- การดูหมิ่นตำแหน่งโดยตรง (ธรรมการอำเภอ)

- ไม่ปรากฏเจตนาเฉพาะต่อผู้แต่งตั้ง

- ศาลจึงจำกัดความรับผิดเฉพาะผู้ที่ถูกกล่าวถึงโดยตรง

3.3 ขอบเขตของความหมายเชิงปฏิบัติการ (Pragmatic Scope)ในภาษาศาสตร์เชิงปฏิบัติ (pragmatics) ความหมายของถ้อยคำไม่ได้อยู่ที่ตัวคำเพียงอย่างเดียว แต่ขึ้นอยู่กับบริบท

อย่างไรก็ตาม การตีความทางกฎหมายต้องยึดหลัก “ความแน่นอน” (legal certainty)

ศาลฎีกาปฏิเสธการตีความแบบขยาย (expansive interpretation) ที่โยงคำว่า “ผู้ตั้ง” ไปยังเสนาบดีโดยอัตโนมัติ เพราะ:

- ไม่มีการระบุชื่อ

- ไม่มีพยานหลักฐานว่าผู้ฟังเข้าใจว่าเป็นบุคคลนั้นโดยเฉพาะ

- ไม่มีหลักฐานว่าจำเลยรับรู้ตัวตนผู้แต่งตั้ง

ต้องตีความโดยเคร่งครัด และห้ามขยายความรับผิดเกินองค์ประกอบที่พิสูจน์ได้

4. ภาระการพิสูจน์ (Burden of Proof)

คำพิพากษานี้ยังสะท้อนหลักภาระการพิสูจน์ในคดีอาญา กล่าวคือ โจทก์ต้องนำสืบให้ได้ว่า:

- จำเลยรู้จักบุคคลผู้ถูกกล่าวถึง

- ถ้อยคำสามารถระบุตัวบุคคลได้

- จำเลยมีเจตนาใส่ความบุคคลนั้น

- เมื่อโจทก์ไม่สามารถพิสูจน์ได้ ศาลจึงยกประโยชน์แห่งความสงสัยให้จำเลย

คำพิพากษานี้มีคุณค่าใน 3 มิติสำคัญ:

- ยืนยันหลัก identifiability ในความผิดฐานหมิ่นประมาท

- จำกัดการตีความถ้อยคำทั่วไปไม่ให้ขยายไปถึงบุคคลเฉพาะโดยไม่มีหลักฐาน

- สะท้อนการประยุกต์หลักภาษาศาสตร์โดยนัย แม้ในยุคก่อนที่คำว่า “forensic linguistics” จะได้รับการบัญญัติอย่างเป็นทางการ

6. สรุป

คำพิพากษาศาลฎีกาที่ 413/2480 แสดงให้เห็นว่า ความผิดฐานหมิ่นประมาทต้องตั้งอยู่บนการระบุตัวบุคคลที่ชัดเจนและเจตนาที่พิสูจน์ได้

ถ้อยคำกว้าง ๆ ที่ไม่สามารถระบุบุคคลเฉพาะรายได้ ไม่อาจขยายความรับผิดไปถึงบุคคลนั้นโดยอัตโนมัติ

แนววินิจฉัยดังกล่าวสะท้อนหลักความแน่นอนในกฎหมายอาญา และสอดคล้องกับหลักการวิเคราะห์ภาษาศาสตร์เชิงนิติวิทยาอย่างมีนัยสำคัญ

เอกสารอ้างอิง (References)

- Coulthard, M., Johnson, A., & Wright, D. (2017). An introduction to forensic linguistics: Language in evidence (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Shuy, R. W. (1993). Language crimes: The use and abuse of language evidence in the courtroom. Blackwell.

- Tiersma, P. M. (1999). Legal language. University of Chicago Press.

- ประมวลกฎหมายอาญา. (ม.ป.ป.).

- คำพิพากษาศาลฎีกาที่ 413/2480. กองผู้ช่วยผู้พิพากษาศาลฎีกา.

สำนักคณะกรรมการกฤษฎีกาเสนอให้ตราเป็นพระราชกฤษฎีกา โดยกำหนดให้นักแปลที่ขึ้นทะเบียน รวมถึงผู้รับรองการแปลจากสมาคมวิชาชีพหรือสถาบันสอนภาษาที่มีการอบรมและขึ้นทะเบียน สามารถรับรองคำแปลได้ (จดหมายถึงสมาคม SEAProTI ลงวันที่ 28 เม.ย. 2568)

สมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้เป็นสมาคมวิชาชีพแห่งแรกและแห่งเดียวในประเทศไทยและภูมิภาคเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ที่มีระบบรับรองนักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรอง

สำนักงานใหญ่: อาคารบ้านราชครู เลขที่ 33 ห้อง 402 ซอยพหลโยธิน 5 ถนนพหลโยธิน แขวงพญาไท เขตพญาไท กรุงเทพมหานคร 10400 ประเทศไทย

อีเมล: hello@seaproti.com โทรศัพท์: (+66) 2-114-3128 (เวลาทำการ: วันจันทร์–วันศุกร์ เวลา 09.00–17.00 น.