Trial in Absentia Where the Defendant Has Never Appeared in Court: A Comparative Legal Analysis

Author: Wanitcha Sumanat, the president of the Southeast Asian Association of Professional Translators and Interpreters

10 August 2025, Bangkok – Trial in absentia refers to judicial proceedings conducted without the defendant’s presence. This article examines the specific scenario where the defendant has never appeared in court even once. The analysis reviews the legal framework in Thailand, compares it with other jurisdictions, and provides real-world case examples. The findings indicate that Thai law imposes strict limitations on such proceedings, whereas some foreign jurisdictions and international judicial bodies accept them under conditions ensuring that the accused has been informed of the charges and granted a fair opportunity to defend themselves.

Introduction

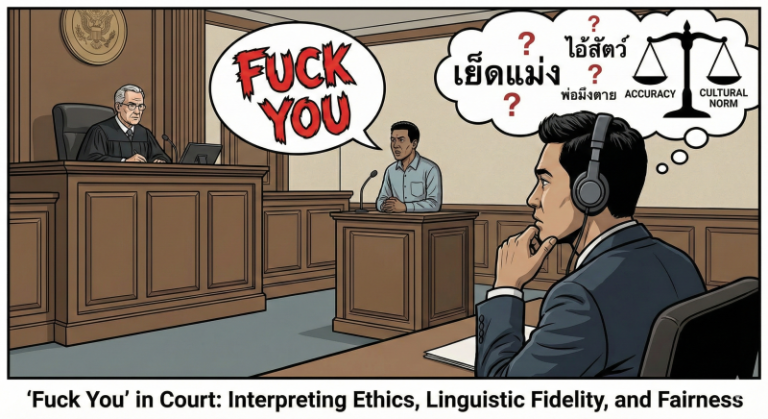

The concept of “trial in absentia” directly concerns the fundamental rights of an accused person in the justice process, as protected under the principle of a fair trial stipulated in Article 14 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) (United Nations, 1966). The specific situation where the defendant has never appeared before the court from the very beginning of the process raises critical questions about compliance with the rights to be informed of charges, to mount a defense, and to have legal counsel.

Thai Law

Under Thai criminal procedure, the Criminal Procedure Code generally requires that the defendant be present during trial proceedings (Sections 172 and 176), except in cases punishable only by a fine or where the court permits representation by counsel (Office of the Council of State, 2023).

Amendments in 2018 introduced Sections 172/2 and 181/1, allowing for trial in absentia if the defendant has “fled” after the commencement of proceedings. However, where the defendant has never appeared even once, such trials are not common practice unless there is clear proof that summonses or indictments were duly served and the defendant deliberately absconded.

General Principle under the Thai Criminal Procedure Code (CPC)

As a general rule, criminal cases must be tried in the presence of the defendant pursuant to Section 172, paragraph 1 of the CPC, reflecting the defendant’s right to be informed of the charges and to confront witnesses (rights to confrontation).

Exceptions — The court may conduct a trial in absentia in special circumstances:

- If the defendant fails to appear without reasonable cause (e.g., absconding) after the court has issued an arrest warrant, and the defendant cannot be apprehended within three months, and the court deems it “appropriate for the interest of justice,” and the defendant has legal counsel, the court has the authority to proceed with the trial and hear witnesses in the defendant’s absence.

- If the defendant has a genuine necessity, such as illness or an unavoidable impediment, and the defendant has legal counsel and the court grants permission to be absent, the court may proceed in absentia under Section 172 bis (4).

- If the defendant obstructs the proceedings (e.g., the court orders the defendant to leave the courtroom, or the defendant departs without permission), the court may continue the trial in absentia under Section 172 bis (5).

Conclusion

- If the defendant fails to appear without reasonable cause (e.g., absence without justification), the court may conduct the trial in absentia only when an arrest warrant has been issued, the defendant cannot be apprehended within three months, the defendant has legal counsel, and the court considers it in the interest of justice.

- If the defendant has a valid reason but has legal counsel and court permission (e.g., illness), the court may proceed in absentia in accordance with the law.

In civil proceedings, however, default judgments are routine when a defendant fails to submit a defense or appear as scheduled (Civil Procedure Code, Section 198).

Foreign Law

Several European countries, such as France, Italy, and Switzerland, permit trial in absentia even where the defendant has never appeared, provided it is proven that they were duly informed of the charges and trial dates (Council of Europe, 2019).

In the United States, the general rule is that a defendant must be present in criminal cases involving serious charges (Fed. R. Crim. P. 43), unless they waive this right or abscond during the proceedings. The International Criminal Court (ICC) and the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) accept trial in absentia, but only if the defendant’s right to request a retrial upon appearance is guaranteed (International Criminal Court, 2021; Colozza v. Italy, 1985).

Case Examples

- Political cases in some jurisdictions have involved sentencing former leaders in exile who never attended any proceedings, often criticized as politically motivated uses of the justice system to eliminate opponents.

- International civil cases involving debt recovery or damages against foreign defendants often proceed to judgment without the defendant’s participation, as permitted under relevant civil codes.

Conclusion

A trial in absentia, where the defendant has never appeared in court, is a sensitive human rights issue. In Thailand, such criminal proceedings are rare and generally require proof that the defendant was duly informed but deliberately failed to appear. In contrast, some foreign jurisdictions allow such trials under conditions safeguarding fundamental rights. Mechanisms ensuring retrial rights and procedural fairness are crucial to preventing abuses of justice.

References

- Colozza v. Italy, App. No. 9024/80, 7 EHRR 516 (Eur. Ct. H.R. 1985).

- Council of Europe. (2019). Guide on Article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights – Right to a fair trial (criminal limb). Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

- International Criminal Court. (2021). Rules of Procedure and Evidence. The Hague: ICC.

- Office of the Council of State. (2023). Criminal Procedure Code [in Thai]. Retrieved from https://www.krisdika.go.th

- United Nations. (1966). International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Treaty Series, 999, 171.

- Natthapong, S. (n.d.). Reo Absente: For the case of the accused is under the judicial power but evaded from the authorities and the trial procedure related to the corruption and malfeasance cases. Central Criminal Court for Corruption and Misconduct Cases.

About SEAProTI Certified Translators, Certification Providers, and Interpreters

The Southeast Asian Association of Professional Translators and Interpreters (SEAProTI) has published official guidelines and eligibility criteria for individuals seeking registration as Certified Translators, Translation Certification Providers, and Certified Interpreters under Chapter 9 and Chapter 10 of the Royal Thai Government Gazette, issued by the Secretariat of the Cabinet, Office of the Prime Minister, on 25 July 2024 (Vol. 141, Part 66 Ng, p. 100). Full text available at: The Royal Thai Government Gazette

การพิจารณาคดีลับหลังโดยที่จำเลยไม่เคยมาศาลเลย: การวิเคราะห์เชิงกฎหมายเปรียบเทียบ

ผู้เขียน วณิชชา สุมานัส นายกสมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ (SEAProTI)

10 สิงหาคม 2568, กรุงเทพมหานคร – การพิจารณาคดีลับหลัง (trial in absentia) เป็นกระบวนการที่ศาลดำเนินการพิจารณาและพิพากษาโดยไม่มีการปรากฏตัวของจำเลย บทความนี้วิเคราะห์กรณีเฉพาะที่จำเลยไม่เคยปรากฏตัวต่อศาลเลยแม้แต่ครั้งเดียว โดยพิจารณากรอบกฎหมายของประเทศไทย เปรียบเทียบกับต่างประเทศ และยกตัวอย่างจากคดีจริง บทวิเคราะห์ชี้ให้เห็นว่ากฎหมายไทยมีข้อจำกัดอย่างมากต่อการพิจารณาในลักษณะนี้ ขณะที่บางประเทศและองค์กรตุลาการระหว่างประเทศยอมรับได้หากมีการแจ้งข้อหาและโอกาสในการต่อสู้คดีอย่างเพียงพอ

บทนำ

แนวคิดเรื่อง “การพิจารณาคดีลับหลัง” เป็นประเด็นที่เกี่ยวข้องโดยตรงกับสิทธิขั้นพื้นฐานของผู้ถูกกล่าวหาในกระบวนการยุติธรรม ตามหลักการพิจารณาอย่างเป็นธรรม (fair trial) ที่รับรองไว้ในกติการะหว่างประเทศว่าด้วยสิทธิพลเมืองและสิทธิทางการเมือง (ICCPR) มาตรา 14 (United Nations, 1966) กรณีที่จำเลยไม่เคยปรากฏตัวต่อศาลเลยตั้งแต่เริ่มกระบวนการ เป็นสถานการณ์ที่ต้องพิจารณาว่าสอดคล้องกับสิทธิในการได้รับแจ้งข้อหา สิทธิในการต่อสู้คดี และสิทธิในการมีทนายความหรือไม่

กฎหมายไทย

ในกระบวนการพิจารณาคดีอาญาของไทย ประมวลกฎหมายวิธีพิจารณาความอาญา กำหนดหลักทั่วไปว่าจำเลยต้องมาศาลระหว่างการพิจารณา (มาตรา 172 และ 176) เว้นแต่เป็นความผิดที่มีโทษเพียงปรับ หรือศาลอนุญาตให้มอบอำนาจทนายความแทน (สำนักงานคณะกรรมการกฤษฎีกา, 2566)

การพิจารณาลับหลังถูกเพิ่มข้อยกเว้นในมาตรา 172 ทวิ และ 181/1 หลังการแก้ไขปี พ.ศ. 2561 ซึ่งเปิดโอกาสให้ศาลสามารถดำเนินการได้หากจำเลย “หลบหนี” หลังเข้าสู่กระบวนการแล้ว อย่างไรก็ตาม ในกรณีที่จำเลย ไม่เคยปรากฏตัวเลยแม้แต่ครั้งเดียว กระบวนการพิจารณาจนถึงการพิพากษายังไม่เป็นแนวปฏิบัติทั่วไป เว้นแต่มีการพิสูจน์ว่ามีการส่งหมายเรียกหรือแจ้งข้อหาโดยชอบแล้วจำเลยจงใจหลบหนี

หลักทั่วไปตามประมวลกฎหมายวิธีพิจารณาความอาญา (ป.วิ.อ.)

โดยหลัก คดีอาญาต้องพิจารณาต่อหน้าจำเลย ตามมาตรา 172 วรรคหนึ่ง ป.วิ.อ. — แสดงให้เห็นถึงสิทธิของจำเลยในการรับทราบข้อกล่าวหาและเผชิญหน้า (rights to confrontation)

ยกเว้น มีกรณีพิเศษที่ศาลอาจพิจารณาลับหลังจำเลยได้:

- จำเลยไม่มาศาลโดยไม่มีเหตุสมควร เช่น หลบหนี หลังจากศาลได้ออกหมายจับแล้ว หากยังจับตัวไม่ได้ภายใน 3 เดือน ศาลเห็นว่า “เป็นการสมควรเพื่อประโยชน์แห่งความยุติธรรม” และจำเลยมีทนายความ ศาลมีอำนาจดำเนินการพิจารณาและสืบพยานลับหลังได้

- จำเลยมีเหตุจำเป็นจริง เช่น เจ็บป่วยหรือมีเหตุอันมิอาจก้าวล่วงได้ ซึ่งจำเลยมีทนายแล้วและศาลอนุญาตไม่มา ก็พิจารณาลับหลังได้ตามมาตรา 172 ทวิ (4)

- กรณีจำเลยขัดขวางการพิจารณา เช่น ศาลสั่งให้จำเลยออกจากห้องเองหรือจำเลยก้าวออกโดยไม่อนุญาต ศาลก็อาจพิจารณาต่อไปโดยลับหลังได้ (มาตรา 172 ทวิ (5))

ข้อสรุป

- หาก จำเลยไม่มาศาลโดยไม่มีเหตุสมควร (เช่น ไม่มาอย่างไม่มีเหตุ) ศาล อาจพิจารณาคดีลับหลังได้ เฉพาะเมื่อ ได้ออกหมายจับ และยังไม่สามารถจับตัวจำเลยมาได้ภายใน 3 เดือน และจำเลยมีทนายความแล้ว ศาลเห็นว่าเป็นประโยชน์ต่อความยุติธรรมในการพิจารณา

- หาก จำเลยไม่มีเหตุสมควรจริงๆ แต่มีทนายและศาลอนุญาต เช่น กรณีเจ็บป่วย ศาลก็สามารถพิจารณาลับหลังได้ตามกฎหมาย

ในคดีแพ่ง กลับพบว่ามีการพิพากษาโดยขาดนัด (default judgment) เป็นเรื่องปกติ หากจำเลยไม่ยื่นคำให้การหรือไม่มาศาลตามกำหนด (ประมวลกฎหมายวิธีพิจารณาความแพ่ง มาตรา 198)

กฎหมายต่างประเทศ

หลายประเทศในยุโรป เช่น ฝรั่งเศส อิตาลี และสวิตเซอร์แลนด์ อนุญาตให้พิจารณาลับหลังได้ แม้จำเลยไม่เคยมาศาล หากพิสูจน์ได้ว่าได้รับแจ้งข้อหาและนัดพิจารณาแล้ว (Council of Europe, 2019)

ในสหรัฐอเมริกา หลักทั่วไปกำหนดว่าจำเลยต้องปรากฏตัวในคดีอาญาที่มีโทษร้ายแรง (Fed. R. Crim. P. 43) เว้นแต่จะสละสิทธิหรือหลบหนีระหว่างพิจารณา ส่วนศาลอาญาระหว่างประเทศ (ICC) และศาลสิทธิมนุษยชนยุโรป (ECHR) ยอมรับการพิจารณาลับหลังได้ แต่ต้องคุ้มครองสิทธิในการขอพิจารณาใหม่เมื่อจำเลยปรากฏตัวในภายหลัง (International Criminal Court, 2021; Colozza v. Italy, 1985)

ตัวอย่างกรณีศึกษา

- คดีการเมือง ในบางประเทศ เช่น การพิพากษาจำคุกอดีตผู้นำที่ลี้ภัยต่างประเทศ โดยไม่เคยมาศาลในกระบวนการใด ๆ ซึ่งถูกวิจารณ์ว่าเป็นการใช้กระบวนการยุติธรรมเพื่อขจัดคู่แข่งทางการเมือง

- คดีแพ่งระหว่างประเทศ เช่น การฟ้องร้องเรียกหนี้หรือค่าเสียหายจากจำเลยในต่างประเทศที่ไม่เข้าร่วมพิจารณา ศาลสามารถตัดสินโดยขาดนัดได้ตามกฎหมายแพ่งและพาณิชย์ของประเทศนั้น ๆ

สรุป

การพิจารณาคดีลับหลังโดยที่จำเลยไม่เคยมาศาลเลยเป็นประเด็นที่มีความอ่อนไหวด้านสิทธิมนุษยชน ในประเทศไทย คดีอาญาลักษณะนี้เกิดขึ้นได้ยาก เว้นแต่จะพิสูจน์ได้ว่าจำเลยทราบข้อหาและนัดพิจารณาแต่จงใจไม่มา ขณะที่ต่างประเทศบางแห่งยอมรับได้ภายใต้เงื่อนไขคุ้มครองสิทธิขั้นพื้นฐาน การกำหนดกลไกถ่วงดุลและสิทธิในการขอพิจารณาใหม่จึงเป็นหัวใจสำคัญในการป้องกันการละเมิดสิทธิ

เอกสารอ้างอิง

- Colozza v. Italy, App. No. 9024/80, 7 EHRR 516 (Eur. Ct. H.R. 1985).

- Council of Europe. (2019). Guide on Article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights – Right to a fair trial (criminal limb). Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

- International Criminal Court. (2021). Rules of Procedure and Evidence. The Hague: ICC.

- สำนักงานคณะกรรมการกฤษฎีกา. (2566). ประมวลกฎหมายวิธีพิจารณาความอาญา. สืบค้นจาก https://www.krisdika.go.th

- United Nations. (1966). International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Treaty Series, 999, 171.

- ณัฐพงษ์ สมศักดิ์. (ม.ป.ป.). การพิจารณาคดีลับหลัง กรณีจำเลยอยู่ในอำนาจศาลแล้วแต่ได้หลบหนีไป และกระบวนพิจารณาที่เกี่ยวข้องในคดีทุจริตและประพฤติมิชอบ. ศาลอาญาคดีทุจริตและประพฤติมิชอบกลาง.

เกี่ยวกับนักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรองของสมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้

สมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ (SEAProTI) ได้ประกาศหลักเกณฑ์และคุณสมบัติผู้ที่ขึ้นทะเบียนเป็น “นักแปลรับรอง (Certified Translators) และผู้รับรองการแปล (Translation Certification Providers) และล่ามรับรอง (Certified Interpreters)” ของสมาคม หมวดที่ 9 และหมวดที่ 10 ในราชกิจจานุเบกษา ของสำนักเลขาธิการคณะรัฐมนตรี ในสำนักนายกรัฐมนตรี แห่งราชอาณาจักรไทย ลงวันที่ 25 ก.ค. 2567 เล่มที่ 141 ตอนที่ 66 ง หน้า 100 อ่านฉบับเต็มได้ที่: นักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรอง