Translation Software as a Copyrighted Work:

An Analysis of Supreme Court Judgment No. 5231/2563 and the Scope of Software Use in Business Organizations

13 February 2026, Bangkok—This article examines Supreme Court Judgment No. 5231/2563, with particular emphasis on translation software as a copyrighted computer program under the Copyright Act B.E. 2537 (1994). The case offers important insight into how Thai courts interpret copyright exceptions under Section 32, define the scope of software use within business organizations, and distinguish between general copyright infringement and infringement “for commercial purposes.”

The judgment demonstrates that although translation software functions as a practical internal tool, unauthorized use may still interfere with the copyright owner’s normal exploitation of the work. Consequently, such use cannot be justified as personal use under statutory exceptions. The ruling also carries broader implications for professional translators and for corporate governance in the use of language technologies.

1. Introduction

In the digital economy, translation software and electronic dictionaries are indispensable tools for businesses. They are used for international communication, technical documentation, product descriptions, and cross-border transactions. However, these tools are not merely linguistic aids; legally, they are computer programs protected under copyright law.

The Supreme Court Judgment No. 5231/2563 had to decide if using dictionary and translation software without permission in a business was allowed by copyright law, and if it wasn’t, what kind of legal consequences would follow. This article looks at the Court’s reasoning from both a legal and a policy point of view.

2. Translation Software as a “Computer Program” Under Copyright Law

The Copyright Act B.E. 2537 (1994) protects “computer programs” as copyrighted works (Sections 4 and 6). Any reproduction, adaptation, or communication to the public without authorization constitutes infringement under Section 30(1).

In this case, one of the allegedly infringed works was a dictionary/translation software. The Supreme Court treated this software in the same manner as operating systems and engineering design programs, affirming that language-related software enjoys full copyright protection.

The decision reinforces an important legal principle: software does not receive diminished protection simply because its content involves language data or vocabulary. Regardless of its function, the program itself—its code and structure—remains a protected work.

3. Copyright Exceptions and Corporate Use of Translation Software

The defendants contended that their actions qualified for the exception under Section 32, paragraph two (2), asserting that they utilized the software for their personal gain. The Supreme Court, on the other hand, said that this exception should be read in light of paragraph one of the same section.

Under Section 32, paragraph one, an act constitutes infringement if it conflicts with the normal exploitation of the work or unreasonably prejudices the legitimate rights of the copyright owner.

The Court found that the defendants used the translation software to support their business operations. The software helped the company make money, even though they didn’t sell it or directly offer translation services for money. These actions constituted economic exploitation.

Therefore, the use conflicted with the copyright owner’s normal commercial interests and could not qualify as personal use under the statutory exception.

The ruling clarifies that corporate use differs from private use, even when the software isn’t distributed publicly.

4. Business Use Versus “For Commercial Purposes.”

Although the Supreme Court confirmed that copyright infringement occurred, it disagreed with the lower courts on the classification of the offense as being “for commercial purposes” under Section 69, paragraph two.

The Court distinguished between using software as a business tool and exploiting the software itself as the object of trade. The defendants had used the translation program to facilitate internal production processes, not to generate profit directly from the software itself.

As a result, the Court held that the conduct constituted an offense under Section 69, paragraph one, rather than paragraph two (which applies to infringement for commercial purposes). This distinction affected both the applicable penalties and the statute of limitations.

From a doctrinal perspective, the ruling clarifies that using software within a profit-oriented enterprise does not automatically amount to infringement “for commercial purposes.” The decisive factor is whether profit is derived directly from the copyrighted work itself.

5. Implications for Professional Translators and Language Technology Governance

This judgment has several troubling consequences for the translation profession and for organizations that rely on language technologies.

First, translation software is an economically valuable intellectual property asset. Unauthorized use hurts both the rights of copyright holders and fair competition in the language technology market.

Second, translation work performed within an organization is treated as a commercial activity rather than a private one. Companies that use translation tools without the right licenses are breaking the law.

Third, the case highlights structural limitations in the enforcement of criminal copyright law, particularly regarding the statute of limitations. Because the applicable offense carried only a monetary penalty, the limitation period was short. If infringement is discovered late, enforcement may be barred despite clear evidence of unlawful use.

6. The Role of Certified Translators, Translation Certification Providers, and Certified Interpreters

Although this case centered on copyright infringement involving computer programs, language professionals played a procedural role in the litigation.

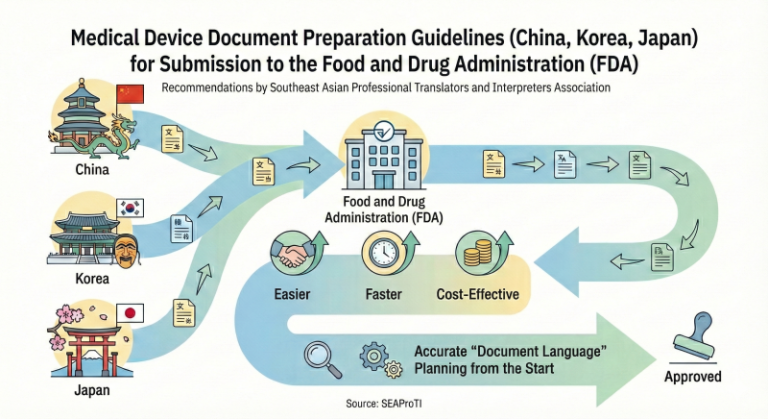

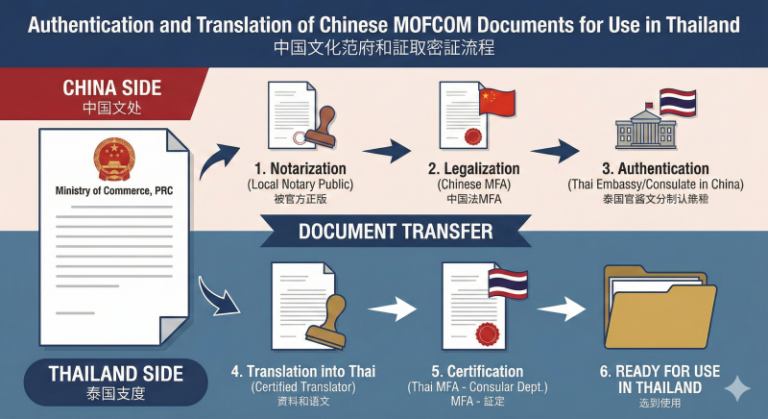

Certified translators were relevant where foreign documents such as powers of attorney, corporate registration documents, or copyright ownership records required translation. Inaccurate translations could affect issues such as standing to sue and evidentiary credibility.

Translation Certification Providers were responsible for certifying the accuracy of translated documents, particularly those involving notarization or consular legalization. Such certification ensured admissibility and reliability in court.

Certified interpreters may have been necessary during hearings if parties or witnesses were foreign nationals. Accurate interpretation was critical, especially where factual details regarding software use influenced the legal classification of the offense as “for commercial purposes” or otherwise.

Thus, even in a technology-focused copyright dispute, professional language services formed part of the procedural framework, ensuring fairness and legal certainty.

7. Conclusion

Supreme Court Judgment No. 5231/2563 reaffirms that translation software is fully protected under copyright law as a computer program. Unauthorized corporate use cannot be justified as personal use under statutory exceptions.

Although the Court distinguished between business use and infringement “for commercial purposes,” thereby reducing the severity of the offense, it nonetheless confirmed that unlicensed use constitutes infringement.

In the digital economy, language technology is not a public resource. It is intellectual property that must be respected and lawfully managed. This judgment stands as a significant reminder that even internal corporate use of translation software must comply with copyright law.

References

- Criminal Code, Sections 83, 95(5).

- Copyright Act B.E. 2537 (1994), Sections 4, 6, 30, 32, 66, 69, 74.

- Supreme Court (Intellectual Property and International Trade Division). (2020). Judgment No. 5231/2563.

The Southeast Asian Association of Professional Translators and Interpreters (SEAProTI) has officially shared the qualifications and requirements for becoming Certified Translators, Translation Certification Providers, and Certified Interpreters in Sections 9 and 10 of the Royal Gazette, which was published by the Prime Minister’s Office in Thailand on July 25, 2024. Certified Translators, Translation Certification Providers, and Certified Interpreters

The Council of State has proposed the enactment of a Royal Decree, granting registered translators and recognised translation certifiers from professional associations or accredited language institutions the authority to provide legally valid translation certification (Letter to SEAProTI dated April 28, 2025)

SEAProTI is the first professional association in Thailand and Southeast Asia to implement a comprehensive certification system for translators, certifiers, and interpreters.

Head Office: Baan Ratchakru Building, No. 33, Room 402, Soi Phahonyothin 5, Phahonyothin Road, Phaya Thai District, Bangkok 10400, Thailand

Email: hello@seaproti.com | Tel.: (+66) 2-114-3128 (Office hours: Mon–Fri, 09:00–17:00)

โปรแกรมแปลภาษาในฐานะงานอันมีลิขสิทธิ์: วิเคราะห์คำพิพากษาศาลฎีกาที่ 5231/2563 กับขอบเขตการใช้ซอฟต์แวร์ในองค์กรธุรกิจ

13 กุมภาพันธ์ 2569, กรุงเทพมหานคร—บทความนี้มุ่งวิเคราะห์คำพิพากษาศาลฎีกาที่ 5231/2563 โดยเน้นประเด็นเกี่ยวกับ “โปรแกรมแปลภาษา” ในฐานะโปรแกรมคอมพิวเตอร์ที่ได้รับความคุ้มครองตามพระราชบัญญัติลิขสิทธิ์ พ.ศ. 2537 กรณีศึกษาดังกล่าวสะท้อนให้เห็นการตีความข้อยกเว้นการละเมิดลิขสิทธิ์ตามมาตรา 32 ขอบเขตของการใช้ซอฟต์แวร์ในองค์กรธุรกิจ และการจำแนกความผิดฐานละเมิดลิขสิทธิ์ “เพื่อการค้า” กับความผิดทั่วไป บทความเสนอว่า โปรแกรมแปลภาษาแม้มีลักษณะเป็นเครื่องมือสนับสนุนงานภายในองค์กร แต่การใช้โดยไม่ได้รับอนุญาตย่อมกระทบต่อการแสวงหาประโยชน์ตามปกติของเจ้าของลิขสิทธิ์ และไม่อาจอ้างข้อยกเว้นเพื่อประโยชน์ส่วนตัวได้ ทั้งยังมีนัยสำคัญต่อวิชาชีพนักแปลและการกำกับดูแลการใช้เทคโนโลยีภาษาในภาคธุรกิจ

1. บทนำ

ในยุคเศรษฐกิจดิจิทัล โปรแกรมแปลภาษาและพจนานุกรมอิเล็กทรอนิกส์เป็นเครื่องมือสำคัญขององค์กรธุรกิจ ไม่ว่าจะใช้ในการสื่อสารกับคู่ค้าต่างประเทศ การจัดทำเอกสารทางเทคนิค หรือการแปลข้อมูลผลิตภัณฑ์ อย่างไรก็ดี โปรแกรมดังกล่าวมิได้เป็นเพียง “เครื่องมือทางภาษา” หากแต่เป็น “โปรแกรมคอมพิวเตอร์” ที่ได้รับความคุ้มครองตามกฎหมายลิขสิทธิ์

คำพิพากษาศาลฎีกาที่ 5231/2563 เป็นกรณีสำคัญที่ศาลต้องพิจารณาว่า การใช้โปรแกรมพจนานุกรม/แปลภาษาในองค์กรธุรกิจโดยไม่ได้รับอนุญาต เข้าข่ายข้อยกเว้นการละเมิดลิขสิทธิ์หรือไม่ และเป็นความผิดระดับใด บทความนี้จึงมุ่งวิเคราะห์ประเด็นดังกล่าวในเชิงกฎหมายและเชิงนโยบาย

2. โปรแกรมแปลภาษาในฐานะ “โปรแกรมคอมพิวเตอร์” ตามกฎหมายลิขสิทธิ์

พระราชบัญญัติลิขสิทธิ์ พ.ศ. 2537 ให้ความคุ้มครอง “โปรแกรมคอมพิวเตอร์” ในฐานะงานอันมีลิขสิทธิ์ (มาตรา 4 และมาตรา 6) การทำซ้ำ ดัดแปลง หรือเผยแพร่ต่อสาธารณชนโดยไม่ได้รับอนุญาตจากเจ้าของลิขสิทธิ์ ย่อมเป็นการละเมิดตามมาตรา 30 (1)

ในคดีที่ศึกษา หนึ่งในโปรแกรมที่ถูกกล่าวหาว่าละเมิดคือโปรแกรมพจนานุกรม/แปลภาษา ซึ่งศาลถือว่าเป็นโปรแกรมคอมพิวเตอร์ที่ได้รับความคุ้มครองเช่นเดียวกับโปรแกรมระบบปฏิบัติการหรือโปรแกรมออกแบบวิศวกรรม การวินิจฉัยดังกล่าวยืนยันหลักการสำคัญว่า ซอฟต์แวร์ด้านภาษาไม่ได้รับสถานะพิเศษหรือลดทอนความคุ้มครองทางกฎหมาย

นัยสำคัญคือ แม้เนื้อหาภายในโปรแกรมจะเกี่ยวข้องกับคำศัพท์หรือข้อมูลทางภาษา แต่ตัวโปรแกรมในฐานะชุดคำสั่งคอมพิวเตอร์ยังคงได้รับความคุ้มครองเต็มรูปแบบ

3. ยกเว้นการละเมิดลิขสิทธิ์กับการใช้โปรแกรมแปลภาษาในองค์กร

จำเลยในคดีอ้างข้อยกเว้นตามมาตรา 32 วรรคสอง (2) ว่าเป็นการใช้เพื่อประโยชน์ของตนเอง อย่างไรก็ตาม ศาลฎีกาวินิจฉัยว่าข้อยกเว้นดังกล่าวต้องอยู่ภายใต้เงื่อนไขในวรรคหนึ่ง กล่าวคือ การกระทำต้องไม่ขัดต่อการแสวงหาประโยชน์จากงานอันมีลิขสิทธิ์ตามปกติ และต้องไม่กระทบกระเทือนสิทธิของเจ้าของเกินสมควร

เมื่อข้อเท็จจริงรับฟังได้ว่าจำเลยใช้โปรแกรมแปลภาษาเพื่อสนับสนุนการดำเนินธุรกิจ ศาลเห็นว่าเป็นการแสวงหาประโยชน์ทางเศรษฐกิจ แม้จะไม่ได้จำหน่ายตัวโปรแกรมหรือให้บริการแปลเชิงพาณิชย์โดยตรง การใช้งานดังกล่าวจึงกระทบต่อรูปแบบการใช้ประโยชน์ตามปกติของเจ้าของลิขสิทธิ์ และไม่เข้าเงื่อนไขข้อยกเว้น

การตีความนี้มีนัยสำคัญ เพราะชี้ให้เห็นว่า “การใช้ในองค์กร” ไม่อาจถือเป็นการใช้ส่วนตัว แม้จะไม่มีการเผยแพร่สู่สาธารณะก็ตาม

4. การจำแนกความผิด: ใช้ในธุรกิจ ≠ เพื่อการค้าโดยตรง

แม้ศาลจะเห็นว่าการใช้โปรแกรมแปลภาษาเป็นการละเมิดลิขสิทธิ์ แต่ศาลฎีกาได้วินิจฉัยแตกต่างจากศาลล่างในประเด็น “เพื่อการค้า” โดยเห็นว่า การใช้โปรแกรมเพื่อสนับสนุนกระบวนการผลิต โดยเห็นว่าการใช้โปรแกรมเพื่อสนับสนุนกระบวนการผลิตมิใช่การแสวงหากำไรจากตัวโปรแกรมโดยตรง

ดังนั้น การกระทำจึงเป็นความผิดตามมาตรา 69 วรรคหนึ่ง มิใช่วรรคสอง (เพื่อการค้า) ความแตกต่างดังกล่าวส่งผลต่อระวางโทษและอายุความ ในเชิงหลักการ แนววินิจฉัยนี้สะท้อนการแยกแยะระหว่าง การใช้โปรแกรมเป็น “เครื่องมือประกอบธุรกิจ” กับการใช้โปรแกรมเป็น “วัตถุแห่งการค้า”

แม้การแยกดังกล่าวช่วยลดความร้ายแรงของความผิด แต่ก็ยังยืนยันว่าการใช้โดยไม่มีใบอนุญาตเป็นการละเมิด

5. นัยต่อวิชาชีพนักแปลและการกำกับดูแลเทคโนโลยีภาษา

คำพิพากษานี้มีนัยสำคัญต่อวิชาชีพนักแปลและองค์กรที่พึ่งพาเทคโนโลยีภาษา ดังนี้

ประการแรก โปรแกรมแปลภาษาเป็นทรัพย์สินทางปัญญาที่มีมูลค่าทางเศรษฐกิจ การละเมิดไม่เพียงกระทบเจ้าของลิขสิทธิ์ แต่ยังบิดเบือนการแข่งขันในตลาดซอฟต์แวร์ภาษา

ประการที่สอง งานแปลในองค์กรถูกมองเป็นกิจกรรมทางธุรกิจ มิใช่กิจกรรมส่วนบุคคล การใช้เครื่องมือแปลภาษาโดยไม่มีสิทธิ์จึงมีความเสี่ยงทางกฎหมาย

ประการที่สาม คดีนี้สะท้อนข้อจำกัดด้านอายุความในคดีอาญาลิขสิทธิ์ ซึ่งอาจทำให้การบังคับใช้กฎหมายไม่มีประสิทธิภาพ หากตรวจพบการละเมิดล่าช้า

6. บทบาทของนักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรองในคดีนี้

แม้คดีนี้เป็นคดีละเมิดลิขสิทธิ์โปรแกรมคอมพิวเตอร์ โดยเฉพาะโปรแกรมแปลภาษา แต่บทบาทของวิชาชีพด้านภาษาในกระบวนพิจารณามีความสำคัญในเชิงกระบวนการ ดังนี้

นักแปลรับรอง (Certified Translators)

มีบทบาทในกรณีที่ต้องแปลเอกสารต่างประเทศ เช่น หนังสือมอบอำนาจจากบริษัทต่างประเทศ เอกสารสิทธิในลิขสิทธิ์ หรือเอกสารทะเบียนบริษัท หากคำแปลคลาดเคลื่อน อาจกระทบต่อประเด็น “อำนาจฟ้อง” และความน่าเชื่อถือของพยานเอกสาร

ผู้รับรองการแปล (Translation Certification Providers)

ทำหน้าที่รับรองความถูกต้องของคำแปล เพื่อให้ศาลเชื่อถือได้ในทางพยานหลักฐาน โดยเฉพาะเอกสารที่ผ่านการรับรองจากต่างประเทศ (เช่น notarization หรือ consular legalization) ซึ่งมีผลต่อการพิสูจน์สถานะนิติบุคคลและสิทธิในลิขสิทธิ์

ล่ามรับรอง (Certified Interpreters)

มีบทบาทในชั้นไต่สวนหรือสืบพยาน หากคู่ความหรือพยานเป็นชาวต่างชาติ ล่ามต้องถ่ายทอดถ้อยคำอย่างถูกต้อง เนื่องจากข้อเท็จจริงเกี่ยวกับการใช้ซอฟต์แวร์ อาจมีผลต่อการจำแนกองค์ประกอบความผิด “เพื่อการค้า” หรือไม่

6. บทสรุป

คำพิพากษาศาลฎีกาที่ 5231/2563 ตอกย้ำว่า โปรแกรมแปลภาษาอยู่ภายใต้ความคุ้มครองของกฎหมายลิขสิทธิ์ในฐานะโปรแกรมคอมพิวเตอร์ การใช้ในองค์กรโดยไม่ได้รับอนุญาตไม่อาจอ้างข้อยกเว้นการใช้เพื่อประโยชน์ส่วนตัวได้ แม้ศาลจะแยกแยะว่าไม่ใช่การละเมิด “เพื่อการค้า” โดยตรงก็ตาม

ในบริบทของเศรษฐกิจดิจิทัล คำพิพากษานี้เป็นหมุดหมายสำคัญที่ย้ำเตือนว่า เทคโนโลยีภาษาไม่ใช่ทรัพยากรสาธารณะ หากแต่เป็นทรัพย์สินทางปัญญาที่ต้องได้รับการเคารพและบริหารจัดการอย่างถูกต้องตามกฎหมาย

เอกสารอ้างอิง

- ประมวลกฎหมายอาญา, มาตรา 83, 95 (5).

- พระราชบัญญัติลิขสิทธิ์ พ.ศ. 2537, มาตรา 4, 6, 30, 32, 66, 69, 74.

- ศาลฎีกาแผนกคดีทรัพย์สินทางปัญญาและการค้าระหว่างประเทศ. (2563). คำพิพากษาศาลฎีกาที่ 5231/2563.

สมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ (SEAProTI) ได้ประกาศหลักเกณฑ์และคุณสมบัติของผู้ที่ขึ้นทะเบียนเป็น “นักแปลรับรอง (Certified Translators) และผู้รับรองการแปล (Translation Certification Providers) และล่ามรับรอง (Certified Interpreters)” ของสมาคม หมวดที่ 9 และหมวดที่ 10 ในราชกิจจานุเบกษา ของสำนักเลขาธิการคณะรัฐมนตรี ในสำนักนายกรัฐมนตรี แห่งราชอาณาจักรไทย ลงวันที่ 25 ก.ค. 2567 เล่มที่ 141 ตอนที่ 66 ง หน้า 100 อ่านฉบับเต็มได้ที่: นักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรอง

สำนักคณะกรรมการกฤษฎีกาเสนอให้ตราเป็นพระราชกฤษฎีกา โดยกำหนดให้นักแปลที่ขึ้นทะเบียน รวมถึงผู้รับรองการแปลจากสมาคมวิชาชีพหรือสถาบันสอนภาษาที่มีการอบรมและขึ้นทะเบียน สามารถรับรองคำแปลได้ (จดหมายถึงสมาคม SEAProTI ลงวันที่ 28 เม.ย. 2568)

สมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้เป็นสมาคมวิชาชีพแห่งแรกและแห่งเดียวในประเทศไทยและภูมิภาคเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ที่มีระบบรับรองนักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรอง

สำนักงานใหญ่: อาคารบ้านราชครู เลขที่ 33 ห้อง 402 ซอยพหลโยธิน 5 ถนนพหลโยธิน แขวงพญาไท เขตพญาไท กรุงเทพมหานคร 10400 ประเทศไทย

อีเมล: hello@seaproti.com โทรศัพท์: (+66) 2-114-3128 (เวลาทำการ: วันจันทร์–วันศุกร์ เวลา 09.00–17.00 น.