Legal and Professional Grounds for the Acceptance of Certified Translations in Singapore Probate Proceedings: The Role of SEAProTI-Licensed Translators

In probate proceedings before the State Court of Singapore, documents originating in Thailand such as death certificates, birth certificates, household registration documents, or other civil registry records must be translated into English before they can be submitted as evidence. This procedural requirement has led to recurring disputes over the admissibility and credibility of translated documents. Notably, Singapore courts often reject translations produced by commercial translation companies in Thailand, even when such translations have been “legalised” by the Department of Consular Affairs of Thailand. Conversely, the courts accept translations that are prepared and certified by professional translators holding a licence or professional accreditation issued by recognised bodies such as the Southeast Asia Professional Translators and Interpreters Association (SEAProTI).

This article provides a systematic analysis of the legal, evidentiary, and professional reasons underlying this judicial practice, with reference to the standards of the Singapore legal system, the evidentiary principles of the common law, and the concept of translation as expert evidence.

1. The Status of Translated Documents in Probate Cases: Translations as Expert Evidence

Under Singapore’s common law–based legal system, probate cases rely heavily on documentary evidence concerning family status, kinship, dates of birth and death, and other personal information essential for determining entitlements under a Grant of Probate or Letters of Administration. When original documents are written in a foreign language, the English translation becomes an indispensable evidentiary component.

Crucially, such translations are treated not as mere administrative aids but as expert evidence, because they involve the application of specialised linguistic knowledge to the interpretation of official documents. The translator therefore occupies a role analogous to that of an expert witness whose work bears directly on the outcome of the proceedings.

From this evidentiary perspective, the court must assess the credibility, qualifications, and accountability of the translator as an individual professional. Translations that originate from commercial agencies without identifiable, individually accountable translators do not meet the standards required for expert evidence in probate matters.

2. Consular Legalisation: Authentication of Signatures, Not Certification of Translation Accuracy

A common misconception in Thailand is that the legalisation process conducted by the Department of Consular Affairs certifies the accuracy of the translation. In fact, the department does not assess or endorse the linguistic quality or substantive accuracy of the translation. Its legal mandate is limited to verifying that the signature on the translated document matches the signature of the person who submitted it.

As a result, a legalised translation:

-

does not confirm that the translation is correct;

-

does not attest to the translator’s competency or qualifications;

-

does not serve as expert certification.

Because of this, Singapore courts cannot rely on consular legalisation as evidence of the translator’s expertise or the reliability of the translation. Therefore, legalisation alone is insufficient to meet evidentiary standards in probate proceedings.

3. Professional Accountability Requirements in a Common Law System

Common law courts place strong emphasis on accountability, particularly when evaluating expert evidence. For a translation to be admissible and credible, the translator must be a person who can demonstrate:

-

recognised professional qualifications;

-

specialised experience in legal and official document translation;

-

submission to professional oversight and disciplinary procedures;

-

adherence to a professional code of ethics;

-

willingness and ability to be examined or cross-examined as an expert if required.

Professional associations such as SEAProTI fulfil these criteria through their systems of peer certification, licensing, continuing professional development, and publicly accessible registries of licensed practitioners. These mechanisms provide the level of professional accountability expected by courts applying common law evidentiary standards.

By contrast, commercial translation companies generally cannot identify a specific professionally accountable individual who takes responsibility for the translation, lack regulatory oversight, and cannot demonstrate compliance with recognised ethical or professional standards.

4. The Legal Consequences of Translation Errors in Probate Matters

Errors in translating key documents—such as inaccuracies in names, dates, kinship relationships, or marital status—can directly affect the legal rights and financial entitlements of beneficiaries. Such errors may result in:

-

wrongful exclusion of rightful heirs;

-

incorrect distribution of estate assets;

-

issuance of a Grant of Probate based on incorrect facts;

-

subsequent legal disputes or cross-border litigation.

Given these serious consequences, the courts require the utmost reliability in translated evidence and will admit only translations produced by properly qualified, licensed professionals who are individually accountable for their work.

5. The Requirement for Translators Accredited in the Country of Origin

Singapore does not maintain its own register or licensing system for Thai-language translators. Therefore, the courts rely on accreditation from the translator’s home jurisdiction or from a recognised professional body within that jurisdiction. This aligns with established common law practices requiring foreign-language experts to demonstrate:

-

qualification in their own country;

-

recognition by a professional body with regulatory authority;

-

verifiable professional standing.

Because Thailand does not have a statutory licensing system for translators or a Notary Public system, SEAProTI serves as the competent professional body capable of issuing licenses and maintaining standards for Thai translators. Consequently, Singapore courts treat SEAProTI-licensed translators as credible expert practitioners capable of producing admissible translations.

Conclusion

The Singapore courts’ rejection of translations produced by commercial agencies in Thailand, despite consular legalisation, reflects not an administrative preference but a principled reliance on professional, evidentiary, and legal standards inherent in the common law system. For translations to be admissible in probate proceedings, they must originate from translators who:

-

hold verifiable professional qualifications;

-

are licensed or certified by a recognised professional body;

-

are individually accountable for the accuracy of their work;

-

are subject to ethical and disciplinary oversight.

Accordingly, translators licensed by the Southeast Asia Professional Translators and Interpreters Association (SEAProTI) meet the level of professional accountability, competence, and traceability required for expert evidence in Singapore probate proceedings. Their translations are therefore accepted by the courts, whereas translations lacking such professional grounding are not.

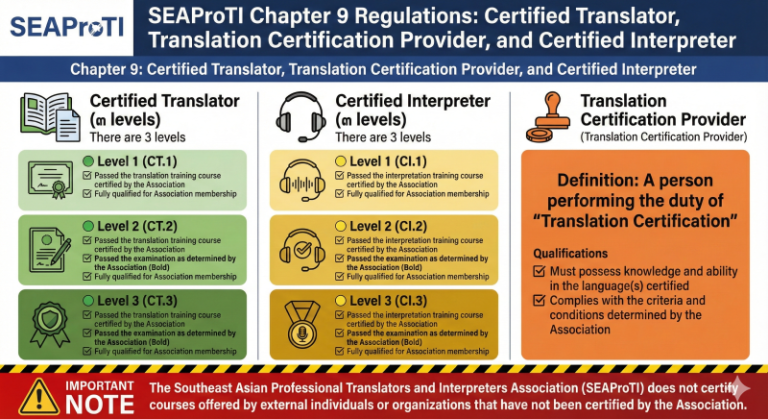

About Certified Translators, Translation Certifiers, and Certified Interpreters of SEAProTI

The Southeast Asian Association of Professional Translators and Interpreters (SEAProTI) has formally announced the qualifications and requirements for registration of Certified Translators, Translation Certification Providers, and Certified Interpreters in Sections 9 and 10 of the Royal Gazette, published by the Secretariat of the Cabinet, Office of the Prime Minister of Thailand, on 25 July 2024 (Vol. 141, Part 66 Ng, p. 100). Certified Translators, Translation Certification Providers, and Certified Interpreters

The Council of State has proposed the enactment of a Royal Decree, granting registered translators and recognized translation certifiers from professional associations or accredited language institutions the authority to provide legally valid translation certification (Letter to SEAProTI dated April 28, 2025)

SEAProTI is the first professional association in Thailand and Southeast Asia to implement a comprehensive certification system for translators, certifiers, and interpreters.

Head Office: Baan Ratchakru Building, No. 33, Room 402, Soi Phahonyothin 5, Phahonyothin Road, Phaya Thai District, Bangkok 10400, Thailand

Email: hello@seaproti.com | Tel.: (+66) 2-114-3128 (Office hours: Mon–Fri, 09:00–17:00)

เหตุผลทางกฎหมายและมาตรฐานวิชาชีพว่าด้วยการยอมรับคำแปลในคดีแบ่งทรัพย์มรดกของศาลสิงคโปร์: การพิจารณาสถานะของผู้แปลจาก SEAProTI

29 พฤศจิกายน 2568, กรุงเทพมหานคร – ในคดีแบ่งทรัพย์มรดก (Probate Proceedings) ของสิงคโปร์ เอกสารสำคัญที่ออกในประเทศไทย เช่น ใบมรณะบัตร สูติบัตร ทะเบียนบ้าน หรือเอกสารทะเบียนราษฎรอื่น ๆ มักต้องผ่านการแปลจากภาษาไทยเป็นภาษาอังกฤษก่อนยื่นต่อศาล กระบวนการนี้ก่อให้เกิดข้อถกเถียงด้านมาตรฐานการรับรองคำแปล เนื่องจากศาลสิงคโปร์มักปฏิเสธคำแปลที่จัดทำโดยบริษัทแปลในประเทศไทย แม้จะผ่านการ “รับรองเอกสาร” (Legalization) โดยกองนิติกรณ์และสัญชาติ ซึ่งเป็นหน่วยงานของรัฐไทย เหตุการณ์ดังกล่าวทำให้เกิดประเด็นสำคัญว่าทำไมศาลสิงคโปร์จึงยอมรับเฉพาะคำแปลที่จัดทำและรับรองโดยนักแปลผู้ถือใบอนุญาตวิชาชีพจากองค์กรวิชาชีพ เช่น สมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ (SEAProTI)

บทความนี้วิเคราะห์เหตุผลเชิงกฎหมาย แนวคิดด้านความน่าเชื่อถือของพยานผู้เชี่ยวชาญ และหลักปฏิบัติตามระบบกฎหมายแบบ Common Law ของสิงคโปร์ เพื่ออธิบายแนวโน้มดังกล่าวอย่างเป็นระบบ

1. ฐานะของคำแปลในคดี Probate: พยานหลักฐานระดับผู้เชี่ยวชาญ

ภายใต้ระบบกฎหมายสิงคโปร์ซึ่งมีรากฐานมาจากระบบ Common Law การพิจารณาคดีมรดกอาศัยเอกสารราชการที่เป็นภาษาอื่นในฐานะหลักฐานสำคัญของสิทธิการสืบสันดาน สถานภาพครอบครัว วันที่ตาย ความสัมพันธ์ทางกฎหมาย และองค์ประกอบอื่นที่ส่งผลต่อการจัดทำ Grant of Probate หรือ Letters of Administration

เมื่อเอกสารเป็นภาษาต่างประเทศ การแปลจึงถือเป็น “พยานหลักฐานประกอบ” ในความหมายของ expert evidence คือเป็นการตีความข้อมูลที่ต้องใช้ความรู้เฉพาะทาง ผู้แปลจึงอยู่ในฐานะผู้เชี่ยวชาญซึ่งคำแปลสามารถส่งผลโดยตรงต่อคำพิพากษา ดังนั้นศาลจำเป็นต้องประเมิน “ความน่าเชื่อถือของผู้แปล” ไม่ใช่เพียงความน่าเชื่อถือของเนื้อหาในเอกสารเท่านั้น

ในมุมนี้ ผู้แปลต้องมีสถานะทางวิชาชีพที่พิสูจน์ได้ และสามารถถูกเรียกตรวจสอบในฐานะผู้เชี่ยวชาญได้ หากคำแปลมีข้อผิดพลาดหรือส่งผลต่อผลของคดี การแปลจากบริษัททั่วไปที่ไม่สามารถระบุผู้รับผิดชอบในระดับบุคคลจึงขาดความน่าเชื่อถือสำหรับศาล

2. การรับรองโดยกองนิติกรณ์และสัญชาติ: การรับรองลายเซ็น ไม่ใช่การรับรองคำแปล

มีความเข้าใจผิดที่พบได้ทั่วไปในประเทศไทยว่า การนำคำแปลไปรับรองที่กรมการกงสุลเป็นการ “รับรองความถูกต้องของคำแปล” ทั้งที่ในความเป็นจริง หน่วยงานดังกล่าวไม่ได้มีหน้าที่รับรองว่าคำแปลถูกต้องหรือเหมาะสมทางวิชาชีพ แต่เพียงรับรองว่า “ลายมือชื่อของผู้แปลเป็นของบุคคลนั้นจริง” ตามหลักการของกฎหมายว่าด้วยเอกสารและลายมือชื่อ

ดังนั้น แม้คำแปลจะผ่านการ Legalization ก็ยังไม่ถือว่าได้รับการรับรองความถูกต้องในเชิงเนื้อหา (substantive accuracy) และไม่ได้เชื่อมโยงกับระบบคุณวุฒิหรือความสามารถของผู้แปลใด ๆ ทำให้ศาลสิงคโปร์ไม่สามารถอ้างอิงการรับรองดังกล่าวเป็นหลักฐานด้านความชำนาญของผู้แปลได้

3. ความจำเป็นของ “ความรับผิดชอบทางวิชาชีพ” ตามมาตรฐาน Common Law

ศาลในประเทศที่ใช้กฎหมายแบบ Common Law ให้ความสำคัญกับ accountability หรือความรับผิดของผู้ให้พยานหลักฐาน ผู้แปลจึงต้องเป็นบุคคลที่สามารถแสดงถึง:

-

คุณวุฒิวิชาชีพ

-

ประสบการณ์เฉพาะด้านการแปลเอกสารกฎหมาย

-

การอยู่ภายใต้สถาบันวิชาชีพที่มีระบบกำกับดูแล

-

ความเป็นกลางและจริยธรรมตามหลักวิชาชีพ

-

ความสามารถที่จะถูกสอบถามหรือไต่สวนในฐานะผู้เชี่ยวชาญหากจำเป็น

องค์กรวิชาชีพ เช่น SEAProTI มีระบบ Peer Certification, การออกใบอนุญาตวิชาชีพ, การกำกับวินัย และทะเบียนผู้ประกอบวิชาชีพที่ตรวจสอบได้ จึงตอบสนองความต้องการของศาลในการประเมินความน่าเชื่อถือของผู้แปล

ตรงกันข้าม บริษัทแปลทั่วไปไม่สามารถแสดงระบบกำกับดูแลในระดับวิชาชีพ หรือระบุผู้รับผิดชอบคำแปลในฐานะปัจเจกบุคคลได้อย่างเป็นทางการ ทำให้คำแปลของบริษัทมักถูกปฏิเสธในคดีที่ต้องการความน่าเชื่อถือสูง เช่น Probate

4. ผลกระทบของคำแปลต่อสิทธิในทรัพย์มรดก

ข้อผิดพลาดในคำแปลเอกสารสำคัญ เช่น วันที่ตาย ชื่อบุคคล ความสัมพันธ์ทางครอบครัว หรือสถานะทางกฎหมาย สามารถสร้างผลทางกฎหมายอย่างกว้างขวาง เช่น

-

การถูกตัดสิทธิจากการเป็นผู้สืบสันดาน

-

การจัดสรรทรัพย์สินผิดพลาด

-

การออก Grant of Probate ผิดเงื่อนไข

-

การเกิดข้อพิพาทหรือคดีฟ้องร้องเพิ่มเติม

ความเสี่ยงดังกล่าวทำให้ศาลยอมรับเฉพาะคำแปลที่มีความรับผิดทางวิชาชีพสูงสุด และสามารถตรวจสอบย้อนกลับได้ถึงตัวผู้แปล เช่น ผู้แปลที่มีใบอนุญาตวิชาชีพจาก SEAProTI

5. เหตุผลที่ศาลต้องการ “ผู้แปลที่ได้รับการรับรองจากประเทศต้นทาง”

ประเทศสิงคโปร์ไม่มีระบบขึ้นทะเบียนนักแปลไทยหรือผู้เชี่ยวชาญภาษาไทยโดยตรง ดังนั้นจึงต้องอาศัยองค์กรวิชาชีพหรือสถาบันรับรองในประเทศต้นทางของเอกสาร เพื่อประเมินความสามารถของผู้แปล โดยหลักปฏิบัติของศาลในเขตอำนาจศาล Common Law มักกำหนดให้:

-

ผู้แปลต้องมีใบอนุญาตหรือการรับรองจากองค์กรวิชาชีพในประเทศที่ออกเอกสาร

-

ผู้แปลต้องสามารถแสดงคุณสมบัติและความรับผิดชอบต่อคำแปล

-

ศาลต้องมีช่องทางตรวจสอบสถานะวิชาชีพได้

เมื่อประเทศไทยไม่มี Notary Public และไม่มีระบบ Licensing ของรัฐในสาขาการแปล สมาคมวิชาชีพอย่าง SEAProTI จึงทำหน้าที่เป็นองค์กรที่ศาลยอมรับในฐานะผู้กำกับมาตรฐานวิชาชีพของนักแปลจากประเทศไทย

บทสรุป

การที่ศาลสิงคโปร์ปฏิเสธคำแปลจากบริษัทแปลในประเทศไทย แม้ผ่านการรับรองลายเซ็นของกองนิติกรณ์และสัญชาติ มิใช่เรื่องของรูปแบบ แต่เป็นประเด็นด้านกฎหมายคุณวุฒิ การประเมินความน่าเชื่อถือของผู้เชี่ยวชาญ และมาตรฐานวิชาชีพที่ศาลยึดถือในกระบวนการพิจารณาคดีมรดก คำแปลที่ได้รับการยอมรับต้องมาจากผู้แปลที่มีความรับผิดทางวิชาชีพสูงสุด มีใบอนุญาตหรือการรับรองจากองค์กรวิชาชีพที่ตรวจสอบได้ และสามารถรับผิดชอบคำแปลของตนในชั้นศาลได้

ดังนั้น นักแปลผู้ได้รับใบอนุญาตประกอบวิชาชีพจาก SEAProTI ซึ่งผ่านระบบประเมินความสามารถ การรับรองคุณวุฒิ และอยู่ภายใต้หลักจรรยาบรรณวิชาชีพ จึงเป็นผู้ที่ศาลสิงคโปร์ให้การยอมรับในฐานะผู้เชี่ยวชาญด้านการแปลจากประเทศไทยในคดี Probate และคดีลักษณะเดียวกัน

เกี่ยวกับนักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรองของสมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้

สมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ (SEAProTI) ได้ประกาศหลักเกณฑ์และคุณสมบัติผู้ที่ขึ้นทะเบียนเป็น “นักแปลรับรอง (Certified Translators) และผู้รับรองการแปล (Translation Certification Providers) และล่ามรับรอง (Certified Interpreters)” ของสมาคม หมวดที่ 9 และหมวดที่ 10 ในราชกิจจานุเบกษา ของสำนักเลขาธิการคณะรัฐมนตรี ในสำนักนายกรัฐมนตรี แห่งราชอาณาจักรไทย ลงวันที่ 25 ก.ค. 2567 เล่มที่ 141 ตอนที่ 66 ง หน้า 100 อ่านฉบับเต็มได้ที่: นักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรอง

สำนักคณะกรรมการกฤษฎีกาเสนอให้ตราเป็นพระราชกฤษฎีกา โดยกำหนดให้นักแปลที่ขึ้นทะเบียน รวมถึงผู้รับรองการแปลจากสมาคมวิชาชีพหรือสถาบันสอนภาษาที่มีการอบรมและขึ้นทะเบียน สามารถรับรองคำแปหฟลได้ (จดหมายถึงสมาคม SEAProTI ลงวันที่ 28 เม.ย. 2568)

สมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ เป็นสมาคมวิชาชีพแห่งแรกในประเทศไทยและภูมิภาคเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ที่มีระบบรับรองนักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรอง

สำนักงานใหญ่: อาคารบ้านราชครู เลขที่ 33 ห้อง 402 ซอยพหลโยธิน 5 ถนนพหลโยธิน แขวงพญาไท เขตพญาไท กรุงเทพมหานคร 10400 ประเทศไทย

อีเมล: hello@seaproti.com โทรศัพท์: (+66) 2-114-3128 (เวลาทำการ: วันจันทร์–วันศุกร์ เวลา 09.00–17.00 น.