Providing Interpreters in Criminal Cases for Foreign Nationals: Misconceptions and Legal Limitations in the Thai Legal System

28 June 2025, Bangkok – This article examines structural limitations in Thai law concerning the provision of interpreters in criminal cases for foreign defendants and suspects. It focuses on the interpretation of Sections 13 and 18 bis of the Thai Criminal Procedure Code, which, although amended to provide greater protection of communication rights in the justice process, still lack clarity on the qualifications of interpreters. Furthermore, there are widespread misconceptions that courts are always obligated to provide interpreters and that interpreters must be “court-registered,” even though Thai law contains no such requirement. This article recommends the establishment of legal qualification standards for interpreters and advocates for accurate public understanding within the context of Thailand’s obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

Introduction

With increasing cross-border migration in the globalized era, Thailand is facing a growing number of criminal cases involving foreign suspects and defendants. Many of these individuals are unable to communicate in Thai, resulting in barriers to exercising their basic rights in the criminal justice system (Sutthiphon, 2002).

Although Thai law has amended Sections 13 and 18 bis of the Criminal Procedure Code to require public officials to provide interpreters in certain cases, the absence of legally defined interpreter qualifications and the lack of an explicit mandate requiring courts to provide interpreters in all circumstances has led to legal and policy ambiguity, and operational misconceptions.

Interpretation of Sections 13 and 18 bis:

Legal Limitations in Thai Statutes

Section 13, paragraph one, of the Criminal Procedure Code stipulates that “if the defendant does not speak or understand Thai, a foreign language, or any language different from Thai, an interpreter shall be used.” The fourth paragraph (added in the 1997 amendment) further states:

“In cases where the injured party, suspect, defendant, or witness cannot speak or understand Thai and no interpreter is available, the inquiry official, public prosecutor, or court shall arrange for an interpreter without delay…” (Office of the Council of State, 1997)

However, the provision does not explicitly require courts to arrange for an interpreter in every case. If a party already has an interpreter, the court may rely on them without being required to appoint a new one. Moreover, the law does not prohibit the use of interpreters who are not registered with any particular agency (Office of the Judiciary, 1998).

Even though the law refers to the appointment of “registered interpreters,” it does not specify any minimum qualifications or professional standards for interpreters in investigative or trial proceedings. This omission raises concerns about the quality of interpretation and the fairness of proceedings (UNOHCHR, 1966).

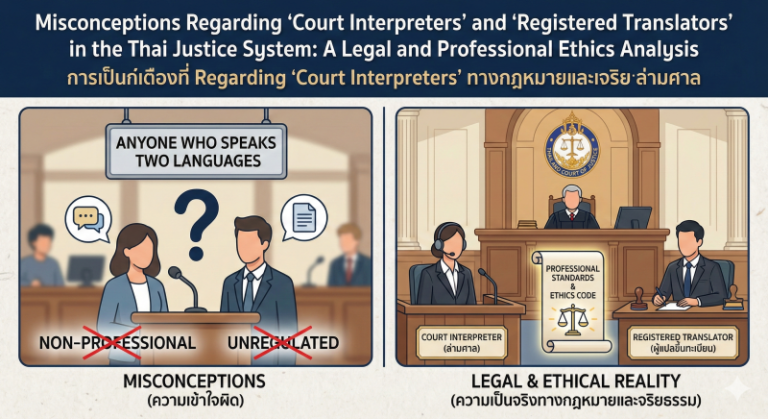

Misconception: “Court Interpreters Must Be Registered with the Court”

A widespread misconception persists that interpreters working in court must be officially certified or registered with the judiciary. This is not legally accurate. There is no officially established “court interpreter registration” system in Thailand. The law only requires that interpreters be sourced from agencies such as the Royal Thai Police or the Office of the Attorney General, with the approval of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. However, there is no regulatory framework equivalent to those in countries with formal interpreter certification laws (Sutthiphon, 2002).

Compliance with International Law

The amendments to Sections 13 and 18 bis were enacted to align with Thailand’s obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), 1966, to which Thailand is a State Party. The ICCPR guarantees criminal defendants the right to be informed of the charges and to defend themselves in a language they understand (United Nations, 1966).

However, this obligation applies only to criminal cases. It does not extend to civil or administrative proceedings. Misunderstandings among public officials and practitioners have led to the erroneous belief that Thai courts must provide interpreters in all cases involving foreign languages, which goes beyond the legal obligations set forth under international law.

Policy Recommendations

- Enact subordinate legislation defining minimum qualifications, ethical standards, and training requirements for interpreters in criminal proceedings.

- Establish a national registry of legal interpreters linked with agencies such as the Courts of Justice, the Royal Thai Police, and the Ministry of Justice.

- Publicly disseminate accurate legal guidelines to correct misconceptions regarding the need for interpreter registration and the court’s obligation to provide interpreters in every case.

- Qualified external professionals should also be allowed to serve as interpreters and should not be arbitrarily excluded

Conclusion

While Thai law has progressed in recognizing the rights of foreign defendants who do not understand Thai in criminal proceedings, the absence of legal qualifications for interpreters and the lack of a universal obligation for courts to provide interpreters remain structural weaknesses. Addressing these gaps is crucial to ensuring that Thailand’s legal system aligns with international human rights standards in both principle and practice.

References

- Office of the Council of State. (1997). Criminal Procedure Code: Amended Version B.E. 2540 (1997). Bangkok: Kurusapha Publishing House.

- Office of the Judiciary. (1998). Regulation on Compensation for Interpreters and Sign Language Interpreters in Criminal Cases B.E. 2541 (1998). Bangkok: Office of the Judiciary.

- Sutthiphon, T. (2002). Assistance for Foreign Defendants in Thai Law: Interpreter Provision in Court Proceedings. Law Journal, 29(2), 45–62.United Nations. (1966). International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). Retrieved from https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-civil-and-political-rights

SEAProTI’s certified translators, translation certification providers, and certified interpreters:

The Southeast Asian Association of Professional Translators and Interpreters (SEAProTI) has officially announced the criteria and qualifications for individuals to register as “Certified Translators,” “Translation Certification Providers,” and “Certified Interpreters” under the association’s regulations. These guidelines are detailed in Sections 9 and 10 of the Royal Thai Government Gazette, issued by the Secretariat of the Cabinet under the Office of the Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Thailand, dated July 25, 2024, Volume 141, Part 66 Ng, Page 100.

To read the full publication, visit the Royal Thai Government Gazette

การจัดหาล่ามในคดีอาญาสำหรับชาวต่างประเทศ: ความเข้าใจผิดและข้อจำกัดเชิงกฎหมายในระบบกฎหมายไทย

28 มิถุนายน 2568, กรุงเทพมหานคร – บทความนี้วิเคราะห์ข้อจำกัดเชิงโครงสร้างในกฎหมายไทยที่เกี่ยวข้องกับการจัดหาล่ามในคดีอาญาสำหรับผู้ต้องหาและจำเลยชาวต่างประเทศ โดยมุ่งเน้นการวิพากษ์บทบัญญัติมาตรา 13 และมาตรา 18 ทวิ แห่งประมวลกฎหมายวิธีพิจารณาความอาญา ซึ่งถึงแม้จะแก้ไขเพิ่มเติมให้มีความคุ้มครองด้านสิทธิในการสื่อสารในกระบวนการยุติธรรม แต่ยังไม่มีการกำหนดคุณสมบัติของล่ามไว้อย่างชัดเจน นอกจากนี้ยังมีความเข้าใจผิดอย่างแพร่หลายว่าศาลมีหน้าที่ต้องจัดหาล่ามให้ทุกกรณี และว่าล่ามต้องเป็น “ล่ามขึ้นทะเบียนศาล” ทั้งที่ข้อเท็จจริงในทางกฎหมายไม่ได้ระบุไว้เช่นนั้น บทความนี้เสนอให้มีการจัดทำมาตรฐานคุณสมบัติล่ามทางกฎหมายและส่งเสริมการเข้าใจที่ถูกต้องในบริบทของพันธกรณีตามกติการะหว่างประเทศ ICCPR

บทนำ

ในยุคโลกาภิวัตน์ที่มีการเคลื่อนย้ายคนข้ามชาติอย่างแพร่หลาย ประเทศไทยต้องเผชิญกับคดีอาญาที่มีผู้ต้องหาและจำเลยเป็นชาวต่างประเทศเพิ่มขึ้นอย่างต่อเนื่อง ซึ่งบุคคลเหล่านี้จำนวนมากไม่สามารถสื่อสารด้วยภาษาไทยได้ ส่งผลให้เกิดอุปสรรคในการเข้าถึงสิทธิขั้นพื้นฐานในกระบวนการยุติธรรม (สุทธิพล, 2545)

แม้กฎหมายไทยจะมีการแก้ไขเพิ่มเติมมาตรา 13 และมาตรา 18 ทวิ แห่งประมวลกฎหมายวิธีพิจารณาความอาญา เพื่อกำหนดให้เจ้าหน้าที่ของรัฐมีหน้าที่จัดหาล่ามในบางกรณี แต่ข้อจำกัดของกฎหมายในด้านการไม่กำหนดคุณสมบัติของล่าม ตลอดจนการไม่บัญญัติให้ “ศาลต้องจัดหาล่ามให้ทุกกรณี” ได้สร้างช่องว่างเชิงนโยบายและนำไปสู่ความเข้าใจผิดในทางปฏิบัติ

การตีความมาตรา 13 และมาตรา 18 ทวิ:

ข้อจำกัดของบทบัญญัติกฎหมายไทย

มาตรา 13 วรรคหนึ่ง ของประมวลกฎหมายวิธีพิจารณาความอาญา ระบุว่า “ถ้าจำเลยมิได้พูดหรือเข้าใจภาษาไทยเป็นภาษาที่ต่างประเทศ หรือภาษาอื่นที่แตกต่างจากไทย ก็ให้ใช้ล่ามแปล” และวรรคสี่ (ที่เพิ่มขึ้นภายหลังในปี 2540) ระบุว่า “ในกรณีที่ผู้เสียหาย ผู้ต้องหา จำเลย หรือพยาน ไม่สามารถพูดหรือเข้าใจภาษาไทยได้ และไม่มีล่าม ให้พนักงานสอบสวน พนักงานอัยการ หรือศาล จัดหาล่ามให้โดยมิชักช้า…” (สำนักงานคณะกรรมการกฤษฎีกา, 2540)

อย่างไรก็ดี บทบัญญัติดังกล่าวไม่ได้กำหนดเป็นการบังคับว่า “ศาลต้องจัดหาล่ามในทุกกรณี” หากมีล่ามของฝ่ายใดฝ่ายหนึ่งอยู่แล้ว ศาลอาจใช้ล่ามดังกล่าวโดยไม่ต้องจัดหาล่ามใหม่ และไม่มีข้อห้ามทางกฎหมายในการใช้ล่ามที่มิได้ขึ้นทะเบียนกับหน่วยงานใดโดยเฉพาะ (สำนักงานศาลยุติธรรม, 2541)

ยิ่งไปกว่านั้น แม้กฎหมายจะระบุว่าให้จัดหาล่ามที่ “ขึ้นทะเบียน” แต่ไม่มีข้อบัญญัติชัดเจนเกี่ยวกับ “คุณสมบัติขั้นต่ำ” หรือ “มาตรฐานวิชาชีพ” ของล่ามที่ใช้ในกระบวนการสอบสวนหรือพิจารณาคดีอาญา ซึ่งส่งผลต่อคุณภาพการแปลและความเป็นธรรมของกระบวนการ (UNOHCHR, 1966)

ความเข้าใจผิดเรื่อง “ล่ามศาลต้องขึ้นทะเบียนศาล”

มีความเข้าใจผิดอย่างแพร่หลายว่า การทำหน้าที่แปลในชั้นศาลจะต้องได้รับการรับรองจาก “ทะเบียนล่ามศาล” หรือหน่วยงานกลางของรัฐ ซึ่งไม่เป็นความจริงในเชิงกฎหมาย ปัจจุบันยังไม่มีระบบ “ขึ้นทะเบียนล่ามศาล” อย่างเป็นทางการในประเทศไทย กฎหมายกำหนดเพียงว่าเจ้าหน้าที่สามารถจัดหาล่ามจากแหล่งที่ได้รับความเห็นชอบ เช่น สำนักงานตำรวจแห่งชาติ หรือสำนักงานอัยการสูงสุด แต่ไม่ได้กำหนดโครงสร้างการรับรองวิชาชีพที่เหมือนกับประเทศที่มีกฎหมายควบคุมวิชาชีพผู้แปลและล่ามโดยตรง (สุทธิพล, 2545)

ความสอดคล้องกับกฎหมายระหว่างประเทศ

การแก้ไขมาตรา 13 และมาตรา 18 ทวิ เกิดขึ้นเพื่อให้สอดคล้องกับพันธกรณีที่ประเทศไทยในฐานะรัฐภาคีของ กติการะหว่างประเทศว่าด้วยสิทธิพลเมืองและสิทธิทางการเมือง ค.ศ. 1966 (ICCPR) ซึ่งรับรองสิทธิของผู้ต้องหาในคดีอาญาในการรับฟังข้อกล่าวหาและต่อสู้คดีด้วยภาษาที่ตนเข้าใจ (United Nations, 1966)

อย่างไรก็ตาม ข้อกำหนดของ ICCPR ดังกล่าวครอบคลุมเฉพาะ “คดีอาญา” เท่านั้น มิได้ขยายความไปถึงคดีแพ่งหรือคดีปกครองแต่อย่างใด ทำให้หลายหน่วยงาน รวมถึงผู้ใช้งานภาครัฐและเอกชนเข้าใจผิดว่า ศาลไทยต้องจัดหาล่ามให้ใน “ทุกกรณีที่มีภาษาต่างประเทศ” ซึ่งไม่เป็นความจริงและเกินขอบเขตของพันธกรณีทางกฎหมาย

ข้อเสนอเชิงนโยบาย

- ออกกฎหมายลำดับรอง เพื่อกำหนดคุณสมบัติขั้นต่ำของล่ามในคดีอาญา รวมถึงหลักจริยธรรมและการฝึกอบรมวิชาชีพ

- สร้างระบบทะเบียนกลางสำหรับล่ามในคดีอาญา ที่เชื่อมโยงกับหน่วยงานด้านความยุติธรรม เช่น ศาลยุติธรรม สำนักงานตำรวจแห่งชาติ และกระทรวงยุติธรรม

- เผยแพร่แนวปฏิบัติทางกฎหมายสู่สาธารณะ เพื่อป้องกันความเข้าใจผิดเรื่องการบังคับใช้ล่ามขึ้นทะเบียนหรือหน้าที่ของศาลในการจัดหาล่ามในทุกกรณี

- ไม่ควรกีดกันให้ผู้เชี่ยวชาญภายนอกให้ปฏิบัติหน้าที่ล่ามได้ด้วย

บทสรุป

แม้ว่ากฎหมายไทยได้มีพัฒนาการด้านสิทธิในกระบวนการยุติธรรม โดยเฉพาะการรับรองสิทธิของชาวต่างประเทศที่ไม่เข้าใจภาษาไทยในคดีอาญา แต่การที่กฎหมายมิได้กำหนดคุณสมบัติของล่ามไว้อย่างชัดเจน และไม่ได้บังคับให้ศาลต้องจัดหาล่ามในทุกกรณี ยังคงเป็นปัญหาเชิงโครงสร้างที่ต้องการการปรับปรุง ทั้งนี้เพื่อให้ระบบกฎหมายไทยเป็นไปตามมาตรฐานสิทธิมนุษยชนสากลโดยแท้จริง

เอกสารอ้างอิง

- สำนักงานคณะกรรมการกฤษฎีกา. (2540). ประมวลกฎหมายวิธีพิจารณาความอาญา ฉบับแก้ไขเพิ่มเติม พ.ศ. 2540. กรุงเทพฯ: สำนักพิมพ์คุรุสภา.

- สำนักงานศาลยุติธรรม. (2541). ระเบียบว่าด้วยการจ่ายค่าตอบแทนการแปลล่ามและล่ามภาษามือในคดีอาญา พ.ศ. 2541. กรุงเทพฯ: สำนักงานศาลยุติธรรม.

- สุทธิพล ทวีชัยการ. (2545). การช่วยเหลือผู้ต้องหาและจำเลยชาวต่างประเทศตามกฎหมายไทย: การจัดหาล่ามในชั้นศาล. วารสารกฎหมาย, 29(2), 45–62.

- United Nations. (1966). International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-civil-and-political-rights

อ่านเพิ่มเติม: การช่วยเหลือผู้ต้องหาและจำเลยชาวต่างประเทศตามกฎหมายไทย : การจัดหาล่ามในชั้นศาล ดร. สุทธิพล ทวีชัยการ* จากวารสาร ดุลพาห (ดาวโหลดไฟล์แนบ)

เกี่ยวกับนักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรองของสมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้

สมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ (SEAProTI) ได้ประกาศหลักเกณฑ์และคุณสมบัติผู้ที่ขึ้นทะเบียนเป็น “นักแปลรับรอง (Certified Translators) และผู้รับรองการแปล (Translation Certification Providers) และล่ามรับรอง (Certified Interpreters)” ของสมาคม หมวดที่ 9 และหมวดที่ 10 ในราชกิจจานุเบกษา ของสำนักเลขาธิการคณะรัฐมนตรี ในสำนักนายกรัฐมนตรี แห่งราชอาณาจักรไทย ลงวันที่ 25 ก.ค. 2567 เล่มที่ 141 ตอนที่ 66 ง หน้า 100 อ่านฉบับเต็มได้ที่: นักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรอง