LGBTQ and Barriers to Entering the Profession of Court Interpreters:

A Legal and Human Rights Analysis with Comparative Case Studies of Malaysia and the Netherlands

Author: Wanitcha Sumanat, president of the Southeast Asian Association of Professional Translators and Interpreters

9 September 2025, Bangkok – Court interpreting is an essential element in safeguarding fundamental rights, particularly the right to equal and fair access to justice. For individuals who cannot understand the language of the court, interpreters act as a crucial “bridge” that makes legal rights practically enforceable. A pressing question arises: Do LGBTQ individuals have equal opportunities to pursue careers as court interpreters?

Although no clear evidence has been found that any jurisdiction has explicitly prohibited “LGBTQ interpreters” from working in courts, many countries continue to enforce laws and policies that criminalize sexual and gender diversity. Examples include cross-dressing laws or provisions penalizing same-sex relations. These laws not only affect everyday life but also indirectly restrict access to professions within the justice system, including court interpreting.

This article examines how laws and societal norms affect LGBTQ individuals’ opportunities to serve as court interpreters, using a comparative case study of Malaysia, which enforces restrictive laws against LGBTQ people, and the Netherlands, often considered a model in advancing human rights and gender equality.

Conceptual Framework: Rights, Impartiality, and Discrimination

International human rights frameworks such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR, 1948) and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR, 1966) clearly state that all individuals have the right to work and the right to a fair trial without discrimination.

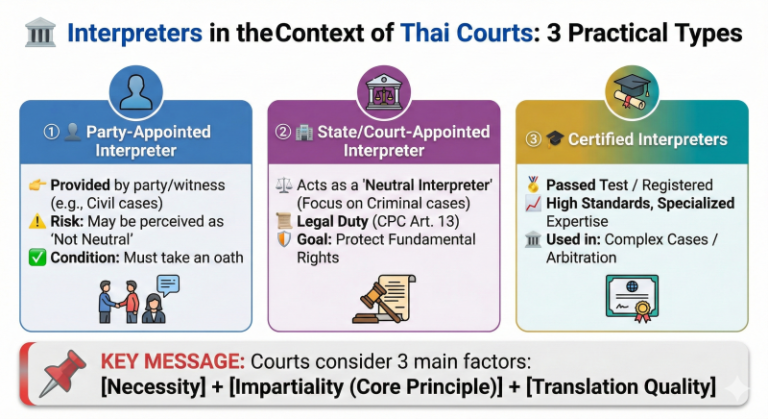

At the same time, the role of court interpreters is firmly rooted in the principles of impartiality and accuracy, as recognized in international practice. For instance, the United States Court Interpreters Act (28 U.S.C. § 1827) requires interpreters to work “without bias.”2 Thus, qualifications for interpreters should be based solely on competence, not sexual orientation or gender identity.

Laws Affecting LGBTQ and Access to Court Interpreting Careers

Cross-Dressing Laws

Several countries maintain laws prohibiting gender expression inconsistent with assigned sex at birth. For example, Malaysia, which applies both civil and Syariah (Islamic) laws, imposes penalties on transgender individuals for “dressing contrary to their sex.”3 Such laws not only restrict personal freedom but also create barriers for professional entry into justice-related roles.

Criminalization of Same-Sex Relations

Countries such as Nigeria, Gambia, and Saudi Arabia continue to impose severe penalties for same-sex relations.4 In such contexts, LGBTQ individuals are not merely excluded from employment but may also face criminal prosecution, making it virtually impossible for them to enter professions within the judiciary.

Structural Discrimination

Even in the absence of explicit court bans, the criminalization of LGBTQ identities functions as structural discrimination. Laws that delegitimize or criminalize LGBTQ existence prevent individuals from passing recruitment processes in government or judicial service, effectively closing off opportunities for court interpreting careers.

Comparative Case Studies

Malaysia: A System of Restriction

Malaysia operates under a dual legal system—civil law and Syariah law. Under Syariah law, transgender individuals can be arrested and prosecuted simply for “cross-dressing.”5 Human Rights Watch (2019) documented widespread use of these laws to arrest transgender persons, often accompanied by harassment aimed at discouraging LGBTQ participation in public life, including civil service roles.

Although there is no explicit regulation prohibiting LGBTQ individuals from becoming court interpreters, recruitment processes in the judiciary often invoke the concept of “public morality,” which is interpreted as excluding LGBTQ candidates. As a result, applicants are frequently denied opportunities, either by being rejected at early stages or being informally disqualified.

The Netherlands: A Model of Inclusion

By contrast, the Netherlands has long been a pioneer in LGBTQ rights, becoming the first country in the world to legalize same-sex marriage in 2001. Dutch law strictly prohibits sexual orientation and gender identity discrimination.

Within the Dutch court system, interpreters must register with the Dutch Register of Court Interpreters and Translators. Selection is based solely on linguistic and professional qualifications, without consideration of sexual orientation or gender identity. This policy illustrates how emphasizing merit over personal identity can uphold genuine standards of justice.

Comparative Analysis

The juxtaposition reveals how state law and values are decisive. Malaysia’s criminalization of LGBTQ identities effectively excludes such individuals from court professions, even without an explicit ban. The Netherlands, by contrast, demonstrates how protective legal frameworks ensure equal opportunity by focusing on professional qualifications rather than personal attributes.

Human Rights Dimensions and Comparative Law

Excluding LGBTQ individuals from court interpreting represents a violation of both the right to work and the right to a fair trial, guaranteed under Article 14 of the ICCPR.7

Human rights organizations such as ILGA World and Human Rights Watch emphasize that criminalizing LGBTQ existence not only breaches fundamental rights but also undermines the credibility of justice systems in the eyes of the international community.8 When LGBTQ individuals are prevented from serving as interpreters, it reflects a deeper conflict between domestic law and international human rights norms.

Discussion

The comparative analysis highlights that the problem does not lie in courts explicitly banning LGBTQ interpreters, but rather in the broader legal and social structures that delegitimize LGBTQ identities. When states define LGBTQ existence as “immoral” or “illegal,” judicial recruitment processes inevitably reflect those biases, leading to exclusion by default.

The reliance on vaguely defined notions of “public morality” in recruitment further exacerbates the issue, granting officials broad discretion to discriminate. This undermines both the neutrality of interpreting and the principle of equality in the justice system.

Conclusion and Recommendations

- No jurisdiction explicitly bans LGBTQ interpreters; however, in many countries, particularly in Asia and Africa, the criminalization of LGBTQ identities indirectly prevents access to such roles.

- Malaysia’s case demonstrates how Syariah-based laws stigmatize LGBTQ individuals, creating systemic barriers to entering court professions.

- The Netherlands’ case illustrates how abolishing discriminatory laws and emphasizing professional merit ensures equality in court interpreting careers.

- Policy recommendations: States should repeal laws that criminalize LGBTQ individuals, and courts should ensure interpreter recruitment is based exclusively on linguistic and professional competence, not gender identity or sexual orientation.

References

- Human Rights Watch. (2019). “I’m scared to be a woman”: Human rights abuses against transgender people in Malaysia. Human Rights Watch.

- Human Rights Watch. (2020). World report 2020: Events of 2019. Human Rights Watch.

- ILGA World. (2020). State-sponsored homophobia report. International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association.

- ILGA Europe. (2022). Annual review of the human rights situation of LGBTI people in Europe. ILGA.

- United Nations. (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. United Nations.

- United Nations. (1966). International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 999 UNTS 171.

- Waaldijk, K. (2001). Small change: How the road to same-sex marriage got paved in the Netherlands. Netherlands Journal of Social Sciences, 37(1), 20–35.

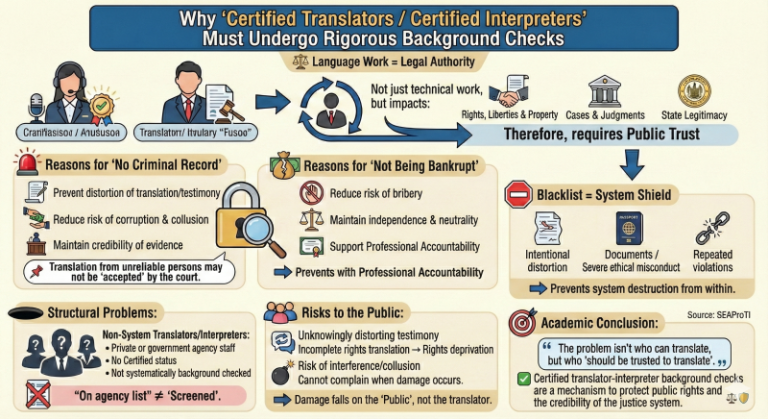

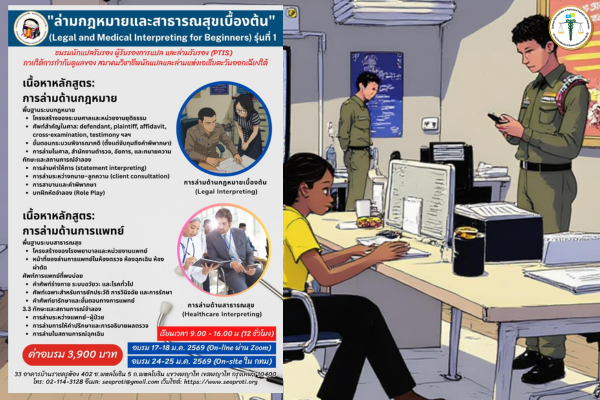

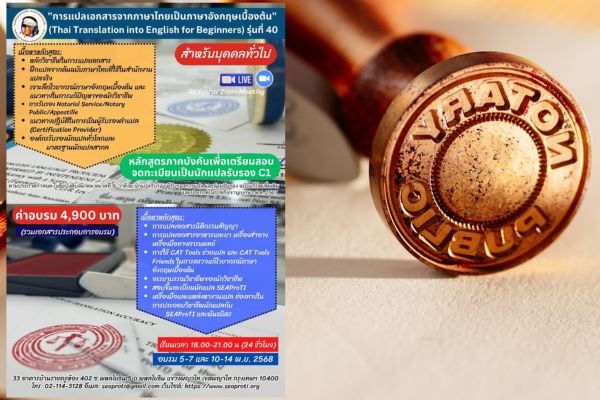

About Certified Translators, Translation Certification Providers, and Certified Interpreters of SEAProTI

The Southeast Asian Association of Professional Translators and Interpreters (SEAProTI) has officially announced the criteria and qualifications for registration of Certified Translators, Translation Certification Providers, and Certified Interpreters under Sections 9 and 10 in the Royal Gazette, Office of the Cabinet Secretariat, Office of the Prime Minister, Kingdom of Thailand, dated 25 July 2024, Vol. 141, Part 66 Ng, p. 100. Certified Translators, Translation Certification Providers, and Certified Interpreters

The Office of the Council of State has proposed a Royal Decree allowing registered translators—including those certified by professional associations or language institutes with training and registration systems—to certify translations (Letter to SEAProTI dated April 28, 2025)

SEAProTI is the first professional association in Thailand and Southeast Asia to establish a comprehensive certification system for translators, translation certification providers, and interpreters.

Headquarters: Baan Ratchakru Building, Room 402, No. 33 Soi Phaholyothin 5, Phaholyothin Road, Phayathai District, Bangkok 10400, Thailand.

Email: hello@seaproti.com Tel: (+66) 2-114-3128 (Office hours: Monday–Friday, 09:00–17:00)

LGBTQ กับข้อจำกัดในการเข้าถึงอาชีพล่ามศาล: การวิเคราะห์เชิงกฎหมายและสิทธิมนุษยชนในเปรียบเทียบมาเลเซียและเนเธอร์แลนด์

ผู้แต่ง วณิชชา สุมานัส นายกสมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้

9 กันยายน 2568, กรุงเทพมหานคร – การล่ามศาล (court interpreting) ถือเป็นองค์ประกอบสำคัญในการคุ้มครองสิทธิขั้นพื้นฐานของผู้เข้ารับการพิจารณาคดี โดยเฉพาะสิทธิในการเข้าถึงกระบวนการยุติธรรมอย่างเสมอภาคและเป็นธรรม หากบุคคลไม่สามารถเข้าใจภาษาของศาลได้ ล่ามจึงทำหน้าที่เป็น “สะพานเชื่อม” ที่ทำให้สิทธิทางกฎหมายเกิดขึ้นจริง แต่คำถามที่ท้าทายคือ บุคคล LGBTQ มีโอกาสเท่าเทียมในการเข้าสู่อาชีพล่ามศาลหรือไม่

แม้ยังไม่พบหลักฐานว่ามีประเทศใดออกข้อห้ามอย่างเป็นทางการว่า “ศาลไม่รับล่ามที่เป็น LGBTQ” แต่หลายประเทศยังคงมีกฎหมายและนโยบายที่ criminalize (ทำให้ผิดกฎหมาย) ความหลากหลายทางเพศ เช่น กฎหมายห้ามแต่งกายข้ามเพศ หรือกฎหมายที่ลงโทษความสัมพันธ์เพศเดียวกัน สิ่งเหล่านี้ไม่เพียงส่งผลต่อสิทธิการดำรงชีวิตประจำวัน แต่ยังปิดกั้นโอกาสในการประกอบอาชีพในระบบยุติธรรม รวมถึงตำแหน่งล่ามศาลด้วย

บทความนี้มุ่งวิเคราะห์ผลกระทบของกฎหมายและค่านิยมต่อการเข้าถึงอาชีพล่ามศาลของ LGBTQ โดยใช้กรณีศึกษาเปรียบเทียบระหว่าง มาเลเซีย ซึ่งยังคงมีกฎหมายที่กดทับ LGBTQ อย่างเข้มงวด และ เนเธอร์แลนด์ ซึ่งถือเป็นประเทศต้นแบบด้านสิทธิมนุษยชนและความเสมอภาคทางเพศ

กรอบแนวคิด: สิทธิ ความเป็นกลาง และการเลือกปฏิบัติ

หลักการสิทธิมนุษยชนสากล เช่น ปฏิญญาสากลว่าด้วยสิทธิมนุษยชน (UDHR, 1948) และ กติการะหว่างประเทศว่าด้วยสิทธิพลเมืองและสิทธิทางการเมือง (ICCPR, 1966) กำหนดไว้อย่างชัดเจนว่า บุคคลทุกคนมีสิทธิในการทำงานและมีสิทธิได้รับการพิจารณาคดีอย่างเป็นธรรม โดยไม่เลือกปฏิบัติ1

ในขณะเดียวกัน บทบาทของล่ามศาลก็มีรากฐานอยู่บนหลักการ ความเป็นกลาง (impartiality) และ ความถูกต้อง (accuracy) ตามมาตรฐานสากล เช่น กฎหมายสหรัฐอเมริกา Court Interpreters Act 28 U.S.C. § 1827 ที่ระบุว่าล่ามต้องทำงาน “โดยไม่ลำเอียง”2 ดังนั้น การพิจารณาคุณสมบัติของล่ามควรตั้งอยู่บนความสามารถ มิใช่เพศสภาพหรือรสนิยมทางเพศ

กฎหมายที่ส่งผลกระทบต่อ LGBTQ และโอกาสในการทำงานล่ามศาล

กฎหมายห้ามการแสดงออกข้ามเพศ

หลายประเทศยังมีกฎหมายที่ห้ามการแต่งกายหรือการแสดงออกทางเพศที่ไม่ตรงกับเพศกำเนิด ตัวอย่างเช่น มาเลเซีย ซึ่งใช้กฎหมายอิสลาม (Syariah laws) ควบคู่กับกฎหมายแพ่ง ได้กำหนดโทษแก่บุคคลข้ามเพศที่ “แต่งกายไม่สอดคล้องกับเพศ”3 กฎหมายลักษณะนี้ไม่เพียงจำกัดเสรีภาพส่วนบุคคล แต่ยังสร้างอุปสรรคในการสมัครงานที่เกี่ยวข้องกับกระบวนการยุติธรรม

กฎหมาย criminalize ความสัมพันธ์เพศเดียวกัน

ประเทศอย่างไนจีเรีย กัมเบีย และซาอุดีอาระเบีย ยังคงมีบทบัญญัติที่กำหนดโทษร้ายแรงต่อความสัมพันธ์เพศเดียวกัน4 ผลลัพธ์คือ LGBTQ ไม่เพียงถูกกีดกันจากการทำงาน แต่ยังอาจถูกดำเนินคดีอาญา ทำให้แทบไม่มีทางเข้าสู่อาชีพในศาลได้

ผลกระทบเชิงโครงสร้าง

แม้ศาลจะไม่ได้ออกข้อห้ามโดยตรง แต่เมื่อกฎหมายของรัฐ criminalize LGBTQ ผู้ที่มีอัตลักษณ์ทางเพศนอกกรอบย่อมไม่ผ่านการคัดเลือกเข้าทำงานในระบบราชการหรือศาล นี่คือตัวอย่างของ การเลือกปฏิบัติทางโครงสร้าง (structural discrimination) ที่ไม่ปรากฏเป็นข้อห้ามชัดเจน แต่ส่งผลเชิงปฏิบัติอย่างรุนแรง

กรณีศึกษาเปรียบเทียบ

มาเลเซีย: ระบบที่กดทับ LGBTQ

มาเลเซียมีระบบกฎหมายคู่ขนานคือ กฎหมายแพ่งและกฎหมายชารีอะห์ (Syariah) ภายใต้กฎหมายชารีอะห์ รัฐสามารถจับกุมและดำเนินคดีกับบุคคลข้ามเพศได้เพียงเพราะ “แต่งกายไม่ตรงเพศ”5 รายงานของ Human Rights Watch (2019) ระบุว่ามีการใช้กฎหมายนี้จับกุมบุคคลข้ามเพศเป็นจำนวนมาก และบางครั้งถูกใช้เพื่อข่มขู่ไม่ให้ LGBTQ มีส่วนร่วมในกิจกรรมสาธารณะ รวมถึงงานราชการ

สำหรับตำแหน่งล่ามศาล แม้จะไม่มีข้อห้ามชัดเจน แต่ระบบการคัดเลือกบุคลากรในศาลมักอ้างอิง “ศีลธรรมอันดี” ซึ่งถูกตีความว่าไม่รวม LGBTQ สิ่งนี้ทำให้ผู้สมัครที่เป็น LGBTQ มักถูกกีดกันโดยอ้อม ไม่ว่าจะเป็นการไม่เรียกสัมภาษณ์หรือการปฏิเสธอย่างไม่เป็นทางการ

เนเธอร์แลนด์: ต้นแบบการคุ้มครองสิทธิ

ในทางตรงกันข้าม เนเธอร์แลนด์ ถือเป็นประเทศแรก ๆ ของโลกที่ให้การรับรองการแต่งงานเพศเดียวกัน (ตั้งแต่ปี 2001) และมีระบบกฎหมายที่ห้ามการเลือกปฏิบัติทางเพศโดยเด็ดขาด6

ในระบบศาลเนเธอร์แลนด์ ล่ามศาลต้องผ่านการขึ้นทะเบียนกับ Dutch Register of Court Interpreters and Translators ซึ่งพิจารณาคุณสมบัติด้านภาษาและวิชาชีพเท่านั้น ไม่มีการสอบถามหรือพิจารณาเพศสภาพหรือรสนิยมทางเพศของผู้สมัคร การเปิดโอกาสนี้สะท้อนให้เห็นว่าระบบกฎหมายที่ให้ความสำคัญกับความสามารถเหนืออัตลักษณ์ส่วนบุคคลสามารถสร้างมาตรฐานความยุติธรรมที่แท้จริงได้

การวิเคราะห์เปรียบเทียบ

เมื่อเปรียบเทียบสองประเทศจะเห็นว่า กฎหมายและค่านิยมของรัฐมีบทบาทชี้ขาด มาเลเซียใช้กฎหมายที่ criminalize LGBTQ ส่งผลให้บุคคลเหล่านี้ไม่อาจเข้าสู่ระบบศาลได้ แม้ในทางทฤษฎีจะไม่มีข้อห้าม ส่วนเนเธอร์แลนด์เลือกใช้ระบบกฎหมายที่คุ้มครองสิทธิและเน้นคุณสมบัติทางวิชาชีพ ทำให้ LGBTQ สามารถมีส่วนร่วมในอาชีพล่ามศาลได้อย่างเท่าเทียม

มิติสิทธิมนุษยชนและกฎหมายเปรียบเทียบ

การกีดกัน LGBTQ จากอาชีพล่ามศาลถือเป็นการละเมิดสิทธิการทำงาน (right to work) และสิทธิในการพิจารณาคดีอย่างเป็นธรรม (fair trial) ซึ่งได้รับการรับรองใน ICCPR มาตรา 147

องค์กรสิทธิมนุษยชน เช่น ILGA World และ Human Rights Watch ชี้ว่าการ criminalize LGBTQ ไม่เพียงเป็นการละเมิดสิทธิมนุษยชน แต่ยังลดทอนความน่าเชื่อถือของระบบยุติธรรมในสายตาสากล8 การที่บุคคล LGBTQ ไม่สามารถเข้าสู่ตำแหน่งล่ามศาลสะท้อนถึงความไม่สมดุลระหว่างกฎหมายภายในประเทศกับมาตรฐานสิทธิมนุษยชนระหว่างประเทศ

อภิปรายผล

การศึกษาเปรียบเทียบชี้ให้เห็นว่า ปัญหาไม่ได้อยู่ที่ศาลออกข้อห้ามโดยตรง แต่เป็นผลจากกฎหมายและค่านิยมของรัฐที่ปฏิเสธความหลากหลายทางเพศ หากรัฐมองว่า LGBTQ เป็น “ผิดศีลธรรม” หรือ “ผิดกฎหมาย” ย่อมทำให้กระบวนการคัดเลือกบุคลากรในศาลมีแนวโน้มกีดกัน LGBTQ โดยปริยาย

นอกจากนี้ การตีความ “ศีลธรรมอันดี” (public morality) ในการรับเข้าทำงานเป็นปัญหาที่เปิดช่องให้เจ้าหน้าที่ใช้ดุลยพินิจเลือกปฏิบัติ ขัดต่อหลักความเป็นกลางและความเท่าเทียมในกระบวนการยุติธรรม

สรุปและข้อเสนอแนะ

- ยังไม่มีประเทศใดประกาศอย่างเป็นทางการว่าไม่รับ LGBTQ เป็นล่ามศาล แต่หลายประเทศโดยเฉพาะในเอเชียและแอฟริกามีกฎหมายที่ criminalize LGBTQ ซึ่งส่งผลให้โอกาสถูกปิดกั้นโดยอ้อม

- กรณีมาเลเซีย แสดงให้เห็นถึงผลกระทบจากกฎหมาย Syariah ที่ตีตรา LGBTQ จนไม่สามารถเข้าสู่ตำแหน่งในศาลได้

- กรณีเนเธอร์แลนด์ แสดงให้เห็นว่าการยกเลิกกฎหมายกีดกันและเน้นการคัดเลือกตามความสามารถสามารถสร้างความเท่าเทียมในอาชีพล่ามศาลได้

- ข้อเสนอเชิงนโยบาย: รัฐควรยกเลิกกฎหมายที่ criminalize LGBTQ และศาลควรกำหนดหลักเกณฑ์การคัดเลือกที่อ้างอิงเพียงความสามารถทางภาษาและความเป็นกลางทางวิชาชีพ ไม่ใช่เพศสภาพ

อ้างอิง:

- Human Rights Watch. (2019). “I’m scared to be a woman”: Human rights abuses against transgender people in Malaysia. Human Rights Watch.

- Human Rights Watch. (2020). World report 2020: Events of 2019. Human Rights Watch.

- ILGA World. (2020). State-sponsored homophobia report. International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association.

- ILGA Europe. (2022). Annual review of the human rights situation of LGBTI people in Europe. ILGA.

- United Nations. (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. United Nations.

- United Nations. (1966). International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 999 UNTS 171.

- Waaldijk, K. (2001). Small change: How the road to same-sex marriage got paved in the Netherlands. Netherlands Journal of Social Sciences, 37(1), 20–35.

About Certified Translators, Translation Certification Providers, and Certified Interpreters of SEAProTI

The Southeast Asian Association of Professional Translators and Interpreters (SEAProTI) has officially announced the criteria and qualifications for registration of Certified Translators, Translation Certification Providers, and Certified Interpreters under Sections 9 and 10 in the Royal Gazette, Office of the Cabinet Secretariat, Office of the Prime Minister, Kingdom of Thailand, dated 25 July 2024, Vol. 141, Part 66 Ng, p. 100. Certified Translators, Translation Certification Providers, and Certified Interpreters

The Office of the Council of State has proposed a Royal Decree allowing registered translators—including those certified by professional associations or language institutes with training and registration systems—to certify translations (Letter to SEAProTI dated April 28, 2025)

SEAProTI is the first professional association in Thailand and Southeast Asia to establish a comprehensive certification system for translators, translation certification providers, and interpreters.

Headquarters: Baan Ratchakru Building, Room 402, No. 33 Soi Phaholyothin 5, Phaholyothin Road, Phayathai District, Bangkok 10400, Thailand.

Email: hello@seaproti.com Tel: (+66) 2-114-3128 (Office hours: Monday–Friday, 09:00–17:00)