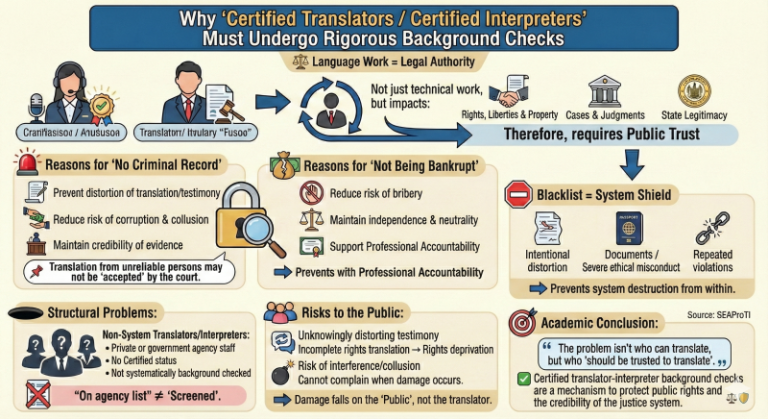

Institutional Credibility and Risks to the Public:

Legal and Ethical Grounds for Background Checks on Certified Translators and Certified Interpreters,

Additionally, there are structural problems associated with non-certified language practitioners.

25 January 2026, Bangkok – Certified translators, translation certification providers, and certified interpreters play a critical role in the justice system, the protection of human rights, and the functioning of the state. This article examines the legal, ethical, and public policy rationales requiring professionals in these fields not to be listed on professional blacklists, to have no criminal record, and not to be subject to bankruptcy proceedings. It further analyzes the structural problems arising from the use of translators and interpreters affiliated with private organizations or certain government agencies who are not subject to systematic background checks, thereby creating direct risks to the public and undermining the legitimacy of the justice system.

Keywords: Certified translators; Certified interpreters; Public trust; Professional ethics; Human rights

1. Introduction: Language Work as an Exercise of Legal Authority

Translation and interpreting in a certified context are not merely technical linguistic activities. Rather, they constitute acts with direct legal consequences, including the use of translated documents as evidence in legal proceedings, the rendering of suspects’ or defendants’ statements, and the communication of legal rights and obligations to individuals who do not speak the official language of the state.

In this context, translators and interpreters function as de facto conveyors of state authority through language. Even minor errors or intentional distortions may directly affect an individual’s personal liberty, property rights, and legal status.

2. The Principle of Public Trust

Public trust constitutes the foundation of professions connected to the administration of justice. Certified translators and interpreters are required to act as neutral and impartial intermediaries, exercising honesty and independence while remaining free from external interference. The requirement that such professionals undergo background checks is therefore not a form of discrimination but a mechanism designed to protect both the public and the justice system as a whole.

In many jurisdictions, this principle applies to high-trust professions such as judges, lawyers, and court-appointed experts and is equally applicable to certified translators and interpreters.

3. The Requirement of No Criminal Record

Criminal records—particularly those involving corruption, document forgery, fraud, money laundering, or transnational crime—signal structural risks to the credibility and neutrality of language professionals.

In practice, courts or government authorities may exclude translations or interpretations produced by individuals lacking credibility from evidentiary consideration. Such exclusion can compromise proceedings from their earliest stages and directly prejudice the rights of the parties involved.

4. The Requirement of Non-Bankruptcy

Although bankruptcy is not a moral failing, in the context of certified professional practice, it reflects limitations on economic independence and civil liability. Individuals subject to bankruptcy proceedings may be more vulnerable to pressure, coercion, or undue influence, which conflicts with the principles of professional accountability and professional neutrality.

5. Professional Blacklists as a Systemic Safeguard

Professional blacklists function as preventive mechanisms against systemic harm. They typically apply to serious breaches of professional ethics, such as deliberate mistranslation, document falsification, or repeated violations of professional standards. Permitting individuals listed on such blacklists to resume work in a certified capacity effectively opens the system to internal erosion.

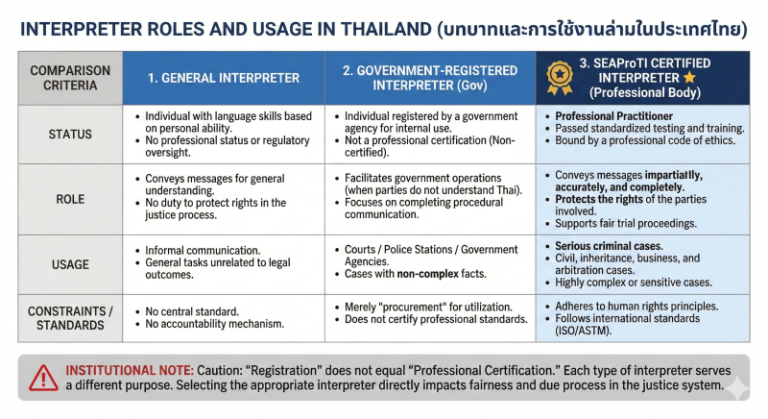

6. Structural Problems of Non-Certified Translators and Interpreters

In practice, a significant number of translators and interpreters operate under private organizations or certain government agencies without holding certified status under a professional regulatory framework. Systematic screening for criminal history, financial status, or ethical compliance does not apply to many of these individuals.

A common misconception is that affiliation with a government agency automatically confers credibility. In reality, inclusion on an agency’s contact list does not equate to having undergone legal and ethical vetting.

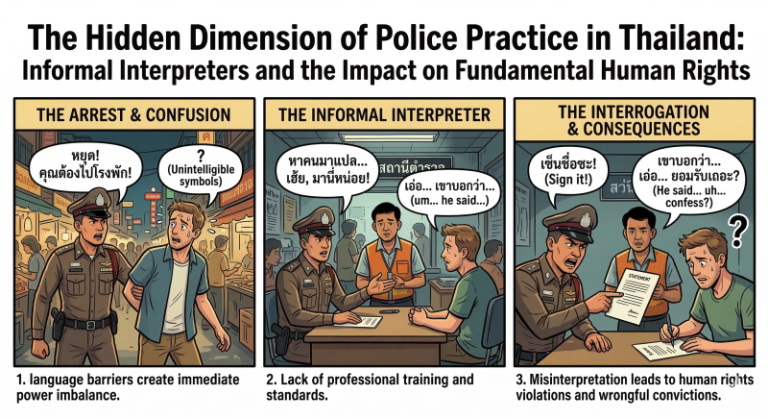

7. Risks to the Public

The use of non-certified language practitioners generates multiple risks, including:

- The use of non-certified language practitioners can lead to the distortion of statements that suspects or victims are unable to independently verify.

- The incomplete or inaccurate translation of legal rights and warnings can result in the inadvertent waiver of fundamental rights.

- Increased vulnerability to collusion, bribery, or external interference; and

- The absence of effective complaint mechanisms and professional accountability when harm occurs.

These consequences do not fall upon the translators or interpreters themselves but upon the public and the overall legitimacy of the justice system.

8. Policy Discussion

The central issue is not who is capable of translating, but who can legitimately be trusted to translate. Continued reliance on translators and interpreters lacking systematic background checks shifts institutional risk onto the public and gradually erodes confidence in the justice system.

9. Conclusion

Requiring certified translators, translation certification providers, and certified interpreters to have a clean criminal record, solvency, and a good professional standing is a reasonable restriction. Rather, it is a protective mechanism safeguarding public rights, institutional credibility, and the rule of law.

Linguistic accuracy is only the starting point; the credibility of the individual is the foundation of justice.

References

- International Organization for Standardization. (2017). ISO 18841: Interpreting services—General requirements and recommendations. ISO.

- International Organization for Standardization. (2015). ISO 17100 outlines the requirements for translation services. ISO.

- The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime published this in 2015. The handbook provides guidance on international cooperation in criminal matters. UNODC.

- United Nations. (2016). The document provides guidance on language services and the rights to a fair trial. United Nations.

- Hale, S. B. (2014). John Benjamins Publishing Company published the book “The discourse of court interpreting” in 2014. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

About Certified Translators, Translation Certifiers, and Certified Interpreters of SEAProTI

The Southeast Asian Association of Professional Translators and Interpreters (SEAProTI) has officially shared the qualifications and requirements for becoming Certified Translators, Translation Certification Providers, and Certified Interpreters in Sections 9 and 10 of the Royal Gazette, which was published by the Prime Minister’s Office in Thailand on July 25, 2024. Certified Translators, Translation Certification Providers, and Certified Interpreters

The Council of State has proposed the enactment of a Royal Decree, granting registered translators and recognised translation certifiers from professional associations or accredited language institutions the authority to provide legally valid translation certification (Letter to SEAProTI dated April 28, 2025)

SEAProTI is the first professional association in Thailand and Southeast Asia to implement a comprehensive certification system for translators, certifiers, and interpreters.

Head Office: Baan Ratchakru Building, No. 33, Room 402, Soi Phahonyothin 5, Phahonyothin Road, Phaya Thai District, Bangkok 10400, Thailand

Email: hello@seaproti.com | Tel.: (+66) 2-114-3128 (Office hours: Mon–Fri, 09:00–17:00)

ความน่าเชื่อถือเชิงสถาบันกับความเสี่ยงต่อประชาชนเหตุผลเชิงกฎหมายและ

จริยธรรมที่นักแปลรับรองและล่ามรับรองต้องผ่านการตรวจประวัติ และปัญหาเชิงโครงสร้างของนักแปล–ล่ามนอกระบบ

25 มกราคม 2569, กรุงเทพมหานคร – นักแปลรับรอง (Certified Translators) ผู้รับรองการแปล (Translation Certification Providers) และล่ามรับรอง (Certified Interpreters) มีบทบาทสำคัญในกระบวนการยุติธรรม การคุ้มครองสิทธิมนุษยชน และการดำเนินงานของรัฐ บทความนี้วิเคราะห์เหตุผลเชิงกฎหมาย จริยธรรม และนโยบายสาธารณะที่กำหนดให้บุคคลในวิชาชีพดังกล่าวต้องไม่อยู่ในบัญชีต้องห้าม (Blacklist) ไม่มีประวัติอาชญากรรม และไม่เป็นบุคคลล้มละลาย พร้อมทั้งอภิปรายปัญหาเชิงโครงสร้างจากการใช้นักแปลและล่ามที่สังกัดหน่วยงานเอกชนหรือหน่วยงานราชการบางแห่งซึ่งไม่มีระบบตรวจสอบประวัติอย่างเป็นระบบ อันก่อให้เกิดความเสี่ยงโดยตรงต่อประชาชนและความชอบธรรมของกระบวนการยุติธรรม

คำสำคัญ: นักแปลรับรอง, ล่ามรับรอง, ความไว้วางใจสาธารณะ, จริยธรรมวิชาชีพ, สิทธิมนุษยชน

1. บทนำ: งานภาษาในฐานะอำนาจทางกฎหมาย

การแปลและการล่ามในบริบทของการ “รับรอง” มิใช่งานทางภาษาเชิงเทคนิคทั่วไป หากแต่เป็นการกระทำที่ก่อให้เกิด ผลผูกพันทางกฎหมาย (legal consequences) โดยตรง เช่น การใช้เอกสารแปลในสำนวนคดี การถ่ายทอดคำให้การของผู้ต้องหา หรือการแปลสิทธิและหน้าที่ตามกฎหมายให้แก่บุคคลที่ไม่ใช้ภาษาไทยเป็นภาษาแม่

ในบริบทนี้ นักแปลและล่ามจึงทำหน้าที่เสมือน “ผู้ถ่ายทอดอำนาจทางภาษาแทนรัฐ” ซึ่งความผิดพลาดหรือการบิดเบือนเพียงเล็กน้อยอาจส่งผลกระทบต่อเสรีภาพในร่างกาย ทรัพย์สิน และสถานะทางกฎหมายของบุคคลโดยตรง

2. หลักความไว้วางใจสาธารณะ (Public Trust)

หลักความไว้วางใจสาธารณะเป็นรากฐานของวิชาชีพที่เกี่ยวข้องกับกระบวนการยุติธรรม นักแปลและล่ามรับรองต้องปฏิบัติหน้าที่ในฐานะบุคคลกลางที่เป็นกลาง ซื่อสัตย์ และไม่ถูกแทรกแซง การกำหนดให้ผู้ประกอบวิชาชีพต้องผ่านการตรวจสอบประวัติ จึงมิใช่การเลือกปฏิบัติ แต่เป็นกลไกคุ้มครองประชาชนและระบบยุติธรรมโดยรวม

ในหลายประเทศ หลักการดังกล่าวถูกใช้กับวิชาชีพที่มีความเสี่ยงสูง (high-trust professions) เช่น ผู้พิพากษา ทนายความ และผู้เชี่ยวชาญในกระบวนการยุติธรรม รวมถึงนักแปลและล่ามรับรองด้วย

3. เหตุผลที่ต้องไม่มีประวัติอาชญากรรม

ประวัติอาชญากรรม โดยเฉพาะคดีที่เกี่ยวข้องกับการทุจริต การปลอมแปลงเอกสาร การฉ้อโกง หรืออาชญากรรมข้ามชาติ สะท้อนถึงความเสี่ยงต่อความน่าเชื่อถือและความเป็นกลางของผู้ปฏิบัติงานด้านภาษา

ในทางปฏิบัติ คำแปลหรือคำล่ามที่มาจากบุคคลซึ่งขาดความน่าเชื่อถือ อาจถูกศาลหรือหน่วยงานรัฐ ไม่รับฟังเป็นพยานหลักฐาน ส่งผลให้กระบวนการยุติธรรมเสียหายตั้งแต่ต้นทาง และกระทบต่อสิทธิของคู่ความโดยตรง

4. เหตุผลที่ต้องไม่เป็นบุคคลล้มละลาย

แม้การล้มละลายจะไม่ใช่ความผิดทางศีลธรรม แต่ในเชิงวิชาชีพรับรอง สถานะดังกล่าวสะท้อนถึงข้อจำกัดด้านอิสระทางเศรษฐกิจและความสามารถในการรับผิดชอบทางแพ่ง บุคคลที่อยู่ในภาวะล้มละลายอาจมีความเสี่ยงต่อการถูกกดดันหรือแทรกแซง ซึ่งขัดกับหลัก professional accountability และความเป็นกลางของวิชาชีพ

5. บัญชีต้องห้าม (Blacklist) ในฐานะกลไกปกป้องระบบ

บัญชีต้องห้ามทางวิชาชีพถูกใช้เป็นกลไกป้องกันความเสียหายเชิงระบบ โดยมักครอบคลุมกรณีการกระทำผิดจรรยาบรรณร้ายแรง เช่น การบิดเบือนคำแปลโดยเจตนา การปลอมเอกสาร หรือการฝ่าฝืนมาตรฐานซ้ำซาก การอนุญาตให้บุคคลในบัญชีดังกล่าวกลับมาทำงานในสถานะ “รับรอง” เท่ากับเปิดช่องให้ระบบถูกบ่อนทำลายจากภายใน

6. ปัญหาเชิงโครงสร้างของนักแปลและล่ามนอกระบบ

ในทางปฏิบัติ ยังมีนักแปลและล่ามจำนวนมากที่สังกัดหน่วยงานเอกชนหรือหน่วยงานราชการบางแห่ง และถูกเรียกใช้งานโดยไม่มีสถานะรับรองตามระบบวิชาชีพ บุคคลเหล่านี้จำนวนมาก ไม่ผ่านการตรวจสอบประวัติอาชญากรรม สถานะทางการเงิน หรือจรรยาบรรณอย่างเป็นระบบ

ความเข้าใจผิดที่พบบ่อยคือ การที่บุคคลใดทำงานให้หน่วยงานรัฐย่อมมีความน่าเชื่อถือโดยอัตโนมัติ ทั้งที่ในความเป็นจริง การอยู่ในรายชื่อผู้ติดต่อของหน่วยงาน มิได้เท่ากับการผ่านการคัดกรองเชิงจริยธรรมและกฎหมาย

7. ความเสี่ยงต่อประชาชน

การใช้นักแปลและล่ามที่อยู่นอกระบบรับรองก่อให้เกิดความเสี่ยงหลายประการ ได้แก่ การบิดเบือนคำให้การโดยที่ผู้ต้องหาหรือผู้เสียหายไม่สามารถตรวจสอบได้ การแปลสิทธิและคำเตือนทางกฎหมายไม่ครบถ้วน ส่งผลให้สิทธิขั้นพื้นฐานถูกลิดรอน ความเสี่ยงต่อการสมรู้ร่วมคิด การติดสินบน หรือการแทรกแซงจากภายนอก การขาดกลไกร้องเรียนและความรับผิดเมื่อเกิดความเสียหาย ผลกระทบเหล่านี้มิได้ตกอยู่กับผู้แปล แต่ตกอยู่กับประชาชนและความชอบธรรมของกระบวนการยุติธรรมทั้งระบบ

8. อภิปรายเชิงนโยบาย

ประเด็นสำคัญมิใช่คำถามว่า “ใครแปลได้” แต่คือ “ใครควรถูกไว้วางใจให้แปล” หากรัฐยังคงพึ่งพานักแปลและล่ามที่ไม่มีระบบตรวจสอบประวัติ ความเสี่ยงจะถูกผลักไปยังประชาชน และบั่นทอนความเชื่อมั่นต่อระบบยุติธรรมในระยะยาว

9. บทสรุป

การกำหนดให้นักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรอง ต้องไม่มีประวัติอาชญากรรม ไม่เป็นบุคคลล้มละลาย และไม่อยู่ในบัญชีต้องห้าม มิใช่เงื่อนไขเกินจำเป็น หากแต่เป็น กลไกคุ้มครองสิทธิประชาชน ความน่าเชื่อถือของรัฐ และหลักนิติธรรม

❝ ความแม่นยำทางภาษาเป็นเพียงจุดเริ่มต้น

แต่ความน่าเชื่อถือของตัวบุคคล คือรากฐานของความยุติธรรม ❞

เอกสารอ้างอิง (References)

- International Organization for Standardization. (2017). ISO 18841: Interpreting services — General requirements and recommendations. ISO.

- International Organization for Standardization. (2015). ISO 17100: Translation services — Requirements for translation services. ISO.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2015). Handbook on international cooperation in criminal matters. UNODC.

- United Nations. (2016). Guidance on language services and fair trial rights. United Nations.

- Hale, S. B. (2014). The discourse of court interpreting. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

เกี่ยวกับนักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรองของสมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้

สมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ (SEAProTI) ได้ประกาศหลักเกณฑ์และคุณสมบัติของผู้ที่ขึ้นทะเบียนเป็น “นักแปลรับรอง (Certified Translators) และผู้รับรองการแปล (Translation Certification Providers) และล่ามรับรอง (Certified Interpreters)” ของสมาคม หมวดที่ 9 และหมวดที่ 10 ในราชกิจจานุเบกษา ของสำนักเลขาธิการคณะรัฐมนตรี ในสำนักนายกรัฐมนตรี แห่งราชอาณาจักรไทย ลงวันที่ 25 ก.ค. 2567 เล่มที่ 141 ตอนที่ 66 ง หน้า 100 อ่านฉบับเต็มได้ที่: นักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรอง

สำนักคณะกรรมการกฤษฎีกาเสนอให้ตราเป็นพระราชกฤษฎีกา โดยกำหนดให้นักแปลที่ขึ้นทะเบียน รวมถึงผู้รับรองการแปลจากสมาคมวิชาชีพหรือสถาบันสอนภาษาที่มีการอบรมและขึ้นทะเบียน สามารถรับรองคำแปลได้ (จดหมายถึงสมาคม SEAProTI ลงวันที่ 28 เม.ย. 2568)

สมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ เป็นสมาคมวิชาชีพแห่งแรกและแห่งเดียวในประเทศไทยและภูมิภาคเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ที่มีระบบรับรองนักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรอง

สำนักงานใหญ่: อาคารบ้านราชครู เลขที่ 33 ห้อง 402 ซอยพหลโยธิน 5 ถนนพหลโยธิน แขวงพญาไท เขตพญาไท กรุงเทพมหานคร 10400 ประเทศไทย

อีเมล: hello@seaproti.com โทรศัพท์: (+66) 2-114-3128 (เวลาทำการ: วันจันทร์–วันศุกร์ เวลา 09.00–17.00 น.