Structural Problems in the Use of Court Interpreters in the Thai Judicial System:

A Comparative Analysis of High-Risk Language Pairs and Judicial Responses to Interpretation Failure

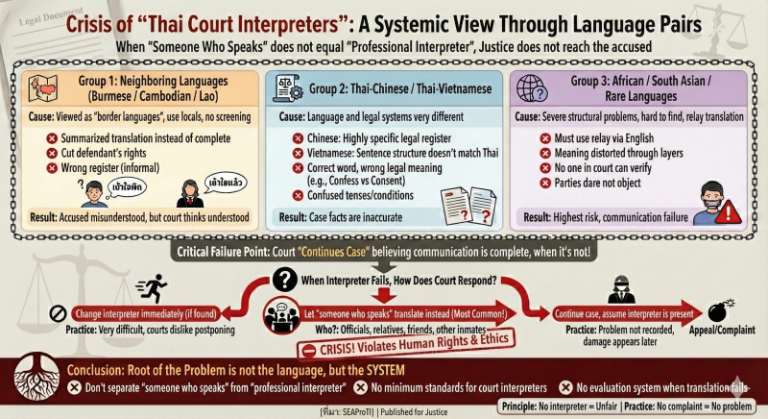

20 January 2026, Bangkok – Court interpreters play a critical role in safeguarding the right to a fair trial, particularly in cases involving parties who are unable to use the Thai language effectively. In practice, however, Thailand’s courts continue to face structural problems concerning the quality of court interpreting, especially in certain high-risk language pairs. This article aims to analyze (1) the language pairs that most frequently encounter problems in court interpreting, (2) the nature of the problems that arise in each language group, and (3) the measures adopted by Thai courts when interpretation fails. The study demonstrates that these problems do not stem from the inherent difficulty of the languages themselves, but rather from the absence of professional standards, systematic screening mechanisms, and effective oversight when interpretation fails. These deficiencies directly affect the rights of litigants and may result in violations of Thailand’s international obligations.

Keywords: court interpreting, right to a fair trial, legal translation, ICCPR, Thai courts

Interpreting as a Core Element of Justice

The provision of interpreting in judicial proceedings is not merely a form of linguistic assistance; it is a fundamental mechanism for ensuring equal access to justice. In comparative legal systems, court interpreters are regarded as an integral part of the adjudicative process rather than as external actors who merely neutrally transmit speech. In the Thai judicial system, however, interpreting is still largely perceived as an operational or logistical matter rather than as a human rights safeguard. As a result, the quality and reliability of interpretation are rarely subject to systematic scrutiny.

Language Pairs Most Prone to Interpreting Problems in Court

Thai–Burmese, Thai–Cambodian, and Thai–Lao

These language pairs present the most frequent problems in practice, not because of linguistic complexity, but due to a structural perception that treats them as “border languages.” Consequently, courts often rely on individuals who can communicate in everyday contexts rather than professional interpreters trained in legal interpreting. Common problems include summarized interpretation, omission of statements relating to defendants’ rights, and the use of inappropriate registers for legal contexts. Such practices may cause significant misunderstandings of substantive legal issues.

Thai–Chinese and Thai–Vietnamese

For these language pairs, the primary difficulty lies in systemic differences between languages and legal concepts. Interpreters lacking specialized legal knowledge may translate terminology accurately at the lexical level while failing at the level of legal meaning. Typical errors involve the inability to distinguish between concepts such as “acknowledgment of rights” and “voluntary consent,” which are crucial in criminal proceedings.

Rare Languages and Relay Interpreting

In cases involving certain African or South Asian languages, Thai courts often face severe shortages of qualified interpreters. This frequently leads to the use of relay interpretation in an intermediary language, most commonly English. Such arrangements multiply the risk of semantic distortion at each stage and leave courts with virtually no tools to verify the accuracy of interpretation during hearings.

Judicial Responses to Interpretation Failure

Ad Hoc Replacement of Interpreters

In principle, courts may replace an interpreter when it becomes apparent that the interpreter cannot perform adequately. In practice, however, particularly for rare language pairs, this option is often unfeasible.

Reliance on Individuals Who “Can Speak the Language”

The most common response is to assign court staff, relatives, or other individuals who can communicate in the relevant language to interpret temporarily. This practice clearly contravenes professional interpreting ethics and violates the principle of impartiality.

Proceeding with the Case on the Assumption That Interpretation Has Been Provided

In some instances, courts proceed with the case on the basis that the mere presence of someone performing an interpretation is sufficient, without formally recording that the interpretation was ineffective. The resulting harm often becomes visible only at the appellate stage or through subsequent complaints.

Implications for International Human Rights Obligations

Thailand is a State Party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights under the framework of the United Nations. The Covenant guarantees accused persons the right to free interpretation if they don’t understand the court’s language. The use of unqualified interpreters, or the treatment of failed interpretation as a purely technical issue, may therefore constitute a breach of Thailand’s international obligations.

Conclusion

This article shows that issues with court interpreting in Thailand are not specific to any one language pair. Instead, they show a fundamental issue caused by the lack of basic standards, professional certification, and proper ways to fix mistakes in interpretation. As long as courts continue to view interpreters merely as “language assistants” instead of as guarantors of the right to a fair trial, the risk of rights violations—particularly for foreign nationals and migrant workers—will remain unavoidable.

References

Hale, S. B. (2004). The discourse of court interpreting. John Benjamins.

Mikkelson, H. (2016). Introduction to court interpreting (2nd ed.). Routledge.

United Nations. (1966). International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. United Nations Treaty Series, 999, 171.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2018). Handbook on language access in criminal justice systems. UNODC.

About Certified Translators, Translation Certifiers, and Certified Interpreters of SEAProTI

The Southeast Asian Association of Professional Translators and Interpreters (SEAProTI) has officially shared the qualifications and requirements for becoming Certified Translators, Translation Certification Providers, and Certified Interpreters in Sections 9 and 10 of the Royal Gazette, which was published by the Prime Minister’s Office in Thailand on July 25, 2024. Certified Translators, Translation Certification Providers, and Certified Interpreters

The Council of State has proposed the enactment of a Royal Decree, granting registered translators and recognised translation certifiers from professional associations or accredited language institutions the authority to provide legally valid translation certification (Letter to SEAProTI dated April 28, 2025)

SEAProTI is the first professional association in Thailand and Southeast Asia to implement a comprehensive certification system for translators, certifiers, and interpreters.

Head Office: Baan Ratchakru Building, No. 33, Room 402, Soi Phahonyothin 5, Phahonyothin Road, Phaya Thai District, Bangkok 10400, Thailand

Email: hello@seaproti.com | Tel.: (+66) 2-114-3128 (Office hours: Mon–Fri, 09:00–17:00)

ปัญหาเชิงโครงสร้างของการใช้ล่ามในศาลไทย:

การเปรียบเทียบคู่ภาษาที่มีความเสี่ยงสูง และมาตรการของศาลเมื่อการแปลล้มเหลว

20 มกราคม 2569, กรุงเทพมหานคร – ล่ามศาลมีบทบาทสำคัญอย่างยิ่งต่อการคุ้มครองสิทธิในการได้รับการพิจารณาคดีอย่างเป็นธรรม โดยเฉพาะอย่างยิ่งในคดีที่คู่ความเป็นบุคคลซึ่งไม่สามารถใช้ภาษาไทยได้อย่างมีประสิทธิภาพ อย่างไรก็ตาม ในทางปฏิบัติของศาลไทย ยังคงปรากฏปัญหาเชิงโครงสร้างเกี่ยวกับคุณภาพล่ามศาล โดยเฉพาะในบางคู่ภาษาที่มีความเสี่ยงสูง บทความนี้มีวัตถุประสงค์เพื่อวิเคราะห์ (1) คู่ภาษาที่ประสบปัญหาการทำหน้าที่ล่ามในศาลมากที่สุด (2) ลักษณะของปัญหาที่เกิดขึ้นในแต่ละกลุ่มภาษา และ (3) มาตรการที่ศาลไทยใช้เมื่อปรากฏว่าล่ามไม่สามารถปฏิบัติหน้าที่ได้อย่างเหมาะสม การศึกษานี้ชี้ให้เห็นว่าปัญหาดังกล่าวไม่ได้เกิดจากความยากง่ายของภาษา หากแต่เป็นผลจากการขาดมาตรฐานวิชาชีพ ระบบคัดกรอง และกลไกตรวจสอบเมื่อการแปลล้มเหลว ซึ่งส่งผลกระทบโดยตรงต่อสิทธิของคู่ความ และอาจก่อให้เกิดการละเมิดพันธกรณีระหว่างประเทศของรัฐไทย

คำสำคัญ: ล่ามศาล, สิทธิในการพิจารณาคดีอย่างเป็นธรรม, การแปลทางกฎหมาย, ICCPR, ศาลไทย

การจัดให้มีล่ามในกระบวนการยุติธรรมไม่ใช่เพียงบริการสนับสนุนทางภาษา หากแต่เป็นกลไกพื้นฐานในการคุ้มครองสิทธิของบุคคลในการเข้าถึงกระบวนการยุติธรรมอย่างเท่าเทียม ในระบบกฎหมายเปรียบเทียบ ล่ามศาลถือเป็นส่วนหนึ่งของ “กระบวนการพิจารณาคดี” มิใช่บุคคลภายนอกที่ทำหน้าที่ถ่ายทอดคำพูดอย่างเป็นกลางเท่านั้น อย่างไรก็ตาม ในการพิจารณาคดีของศาลยุติธรรมไทย การใช้ล่ามยังคงถูกมองในเชิงปฏิบัติการ มากกว่าในฐานะองค์ประกอบด้านสิทธิมนุษยชน ส่งผลให้คุณภาพและความน่าเชื่อถือของการแปลไม่ถูกตรวจสอบอย่างเป็นระบบ

คู่ภาษาที่ประสบปัญหามากที่สุดในการปฏิบัติหน้าที่ล่ามศาล

คู่ภาษาไทย–พม่า ไทย–กัมพูชา และไทย–ลาว

คู่ภาษากลุ่มนี้เป็นกลุ่มที่พบปัญหามากที่สุดในทางปฏิบัติ มิใช่เนื่องจากความซับซ้อนทางภาษา หากแต่เนื่องจากการรับรู้เชิงโครงสร้างที่มองว่าภาษาดังกล่าวเป็น “ภาษาชายแดน” ส่งผลให้ศาลมักใช้บุคคลที่สามารถสื่อสารได้ในชีวิตประจำวัน แทนที่จะเป็นล่ามวิชาชีพที่ผ่านการฝึกอบรมด้านการล่ามกฎหมาย ปัญหาที่พบเป็นประจำ ได้แก่ การแปลแบบสรุปความ การละเว้นถ้อยคำที่เกี่ยวข้องกับสิทธิของจำเลย และการใช้ระดับภาษาที่ไม่เหมาะสมกับบริบททางกฎหมาย ซึ่งอาจทำให้คู่ความเข้าใจสาระสำคัญคลาดเคลื่อนอย่างมีนัยสำคัญ

คู่ภาษาไทย–จีน และไทย–เวียดนาม

ปัญหาของคู่ภาษากลุ่มนี้อยู่ที่ความแตกต่างเชิงระบบระหว่างภาษาและแนวคิดทางกฎหมาย ล่ามที่ขาดความรู้เฉพาะด้านกฎหมายมักแปลได้ถูกต้องในระดับคำศัพท์ แต่ผิดพลาดในระดับนัยทางกฎหมาย เช่น การแยกแยะระหว่าง “การรับทราบสิทธิ” กับ “การยินยอมโดยสมัครใจ” ซึ่งเป็นประเด็นสำคัญในกระบวนการพิจารณาคดีอาญา

ภาษาหายากและการแปลผ่านภาษากลาง

ในกรณีของภาษาแอฟริกันหรือภาษาเอเชียใต้บางภาษา ศาลไทยมักประสบปัญหาขาดแคลนล่ามอย่างรุนแรง ส่งผลให้ต้องใช้การแปลผ่านภาษากลาง เช่น ภาษาอังกฤษ (relay interpreting) ซึ่งเพิ่มความเสี่ยงของการบิดเบือนความหมายหลายชั้น และแทบไม่มีเครื่องมือใดในการตรวจสอบความถูกต้องของการแปลในห้องพิจารณาคดี

มาตรการของศาลไทยเมื่อการแปลล้มเหลว

การเปลี่ยนล่ามเฉพาะหน้า

ในทางหลักการ ศาลสามารถเปลี่ยนล่ามได้เมื่อปรากฏว่าล่ามไม่สามารถปฏิบัติหน้าที่ได้ อย่างไรก็ตาม ในทางปฏิบัติ โดยเฉพาะในคู่ภาษาหายาก ทางเลือกนี้แทบไม่สามารถดำเนินการได้จริง

การใช้บุคคลที่ “พูดได้” แทนล่าม

มาตรการที่พบมากที่สุด คือ การให้เจ้าหน้าที่ ญาติ หรือบุคคลอื่นที่สามารถสื่อสารได้ ทำหน้าที่แปลแทนชั่วคราว ซึ่งขัดต่อหลักจริยธรรมวิชาชีพล่าม และละเมิดหลักความเป็นกลางอย่างชัดเจน

การดำเนินคดีต่อโดยถือว่ามีล่ามแล้ว

ในบางกรณี ศาลเลือกที่จะดำเนินคดีต่อ โดยถือว่าการมีบุคคลทำหน้าที่แปลเพียงพอแล้ว โดยไม่มีการบันทึกอย่างเป็นทางการว่าการแปลไม่สามารถดำเนินการได้อย่างมีประสิทธิภาพ ความเสียหายจึงมักปรากฏในชั้นอุทธรณ์หรือในกระบวนการร้องเรียนภายหลัง

การเชื่อมโยงกับพันธกรณีด้านสิทธิมนุษยชนระหว่างประเทศ

ประเทศไทยเป็นภาคีของกติการะหว่างประเทศว่าด้วยสิทธิพลเมืองและสิทธิทางการเมือง ซึ่งอยู่ภายใต้กรอบของUnited Nations โดยบทบัญญัติดังกล่าวรับรองสิทธิของจำเลยในการได้รับความช่วยเหลือจากล่ามโดยไม่เสียค่าใช้จ่าย หากไม่สามารถเข้าใจหรือใช้ภาษาที่ใช้ในศาลได้อย่างเพียงพอ การใช้ล่ามที่ไม่มีคุณสมบัติ หรือการถือว่าการแปลที่ล้มเหลวเป็นเพียงปัญหาทางเทคนิค จึงอาจเข้าข่ายการละเมิดพันธกรณีระหว่างประเทศของรัฐไทย

บทสรุป

บทความนี้ชี้ให้เห็นว่าปัญหาล่ามศาลในประเทศไทยมิได้จำกัดอยู่ที่คู่ภาษาใดคู่ภาษาหนึ่ง หากแต่เป็นปัญหาเชิงโครงสร้างที่เกิดจากการขาดมาตรฐานขั้นต่ำ ระบบรับรองวิชาชีพ และกลไกตรวจสอบเมื่อการแปลล้มเหลว หากศาลยังคงมองล่ามเป็นเพียง “ผู้ช่วยด้านภาษา” มากกว่าเป็นหลักประกันของสิทธิในการพิจารณาคดีอย่างเป็นธรรม ความเสี่ยงต่อการละเมิดสิทธิของคู่ความ โดยเฉพาะชาวต่างชาติและแรงงานข้ามชาติ จะยังคงดำรงอยู่ต่อไปอย่างหลีกเลี่ยงไม่ได้

เอกสารอ้างอิง

- Hale, S. B. (2004). The discourse of court interpreting. John Benjamins.

- Mikkelson, H. (2016). Introduction to court interpreting (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- United Nations. (1966). International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. United Nations Treaty Series, 999, 171.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2018). Handbook on language access in criminal justice systems. UNODC.

เกี่ยวกับนักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรองของสมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้

สมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ (SEAProTI) ได้ประกาศหลักเกณฑ์และคุณสมบัติของผู้ที่ขึ้นทะเบียนเป็น “นักแปลรับรอง (Certified Translators) และผู้รับรองการแปล (Translation Certification Providers) และล่ามรับรอง (Certified Interpreters)” ของสมาคม หมวดที่ 9 และหมวดที่ 10 ในราชกิจจานุเบกษา ของสำนักเลขาธิการคณะรัฐมนตรี ในสำนักนายกรัฐมนตรี แห่งราชอาณาจักรไทย ลงวันที่ 25 ก.ค. 2567 เล่มที่ 141 ตอนที่ 66 ง หน้า 100 อ่านฉบับเต็มได้ที่: นักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรอง

สำนักคณะกรรมการกฤษฎีกาเสนอให้ตราเป็นพระราชกฤษฎีกา โดยกำหนดให้นักแปลที่ขึ้นทะเบียน รวมถึงผู้รับรองการแปลจากสมาคมวิชาชีพหรือสถาบันสอนภาษาที่มีการอบรมและขึ้นทะเบียน สามารถรับรองคำแปลได้ (จดหมายถึงสมาคม SEAProTI ลงวันที่ 28 เม.ย. 2568)

สมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ เป็นสมาคมวิชาชีพแห่งแรกและแห่งเดียวในประเทศไทยและภูมิภาคเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ที่มีระบบรับรองนักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรอง

สำนักงานใหญ่: อาคารบ้านราชครู เลขที่ 33 ห้อง 402 ซอยพหลโยธิน 5 ถนนพหลโยธิน แขวงพญาไท เขตพญาไท กรุงเทพมหานคร 10400 ประเทศไทย

อีเมล: hello@seaproti.com โทรศัพท์: (+66) 2-114-3128 (เวลาทำการ: วันจันทร์–วันศุกร์ เวลา 09.00–17.00 น.