Structural Problems in the Use of Government-Affiliated Interpreters in the Thai Justice System

Implications for the Right to a Fair Trial under International Standards

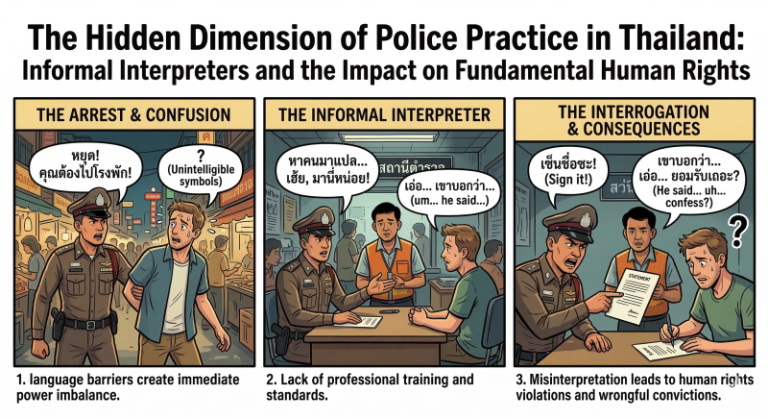

25 January 2026, Bangkok – Interpreters play a crucial role in safeguarding the rights of suspects, defendants, and witnesses in judicial proceedings, particularly in criminal cases involving individuals who are unable to use the Thai language effectively. International fair trial standards clearly establish that every individual has the right to receive assistance from a competent and independent interpreter. However, in the Thai context, the continued reliance on interpreters affiliated with government agencies presents several structural problems that directly affect the accuracy of judicial proceedings and the protection of fundamental human rights.

This article analyzes these issues through three primary dimensions:

(1) inadequate language proficiency that falls short of international standards;

(2) a compensation structure that is grossly disproportionate to professional responsibility; and

(3) interpretive practices that distort the substantive meaning of testimony or legal documents.

1. Language Proficiency and Structural Deficiencies in State Interpreter Registration

Although many government-affiliated interpreters in Thailand are formally “registered” through official administrative procedures, such registration is not accompanied by transparent or verifiable assessments based on internationally recognized language proficiency standards, such as the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR), IELTS, TOEFL, or specialized legal interpreting examinations. The absence of a rigorous qualitative evaluation mechanism has resulted in a significant number of interpreters whose linguistic competence is insufficient for handling complex criminal cases.

This structural deficiency directly contradicts the principles enshrined in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to which Thailand is a State Party under the framework of the United Nations. The ICCPR specifically guarantees that an accused person has the right to receive interpretation and translation that are “adequate and effective,” not just symbolic or procedural. The mere physical presence of an interpreter does not, in itself, satisfy this international obligation.

2. Inadequate Compensation and Negative Incentive Structures

The compensation structure for government-affiliated interpreters in Thailand is markedly low when measured against the level of responsibility, professional risk, and ethical burden associated with legal interpreting. In many border regions, interpreters receive only approximately 300–500 Thai baht per day, while remuneration in more serious cases may increase modestly but rarely exceeds 4,200 Thai baht per day.

By contrast, legal interpreters in the private sector typically receive a minimum of 6,000 Thai baht per day, with rates ranging from 10,000 to 25,000 Thai baht per day in arbitration proceedings or cross-border litigation. This disparity creates significant negative incentives. Field experience and professional complaints show that some interpreters have asked foreign witnesses or suspects for extra money when there is no judicial oversight. Such practices undermine neutrality, erode public trust, and directly compromise the integrity of the justice system.

3. Summarized Interpretation and Distortion of Meaning in Judicial Proceedings

One of the most serious issues concerns the practice of “summarized interpretation,” whereby interpreters with limited competence condense or selectively convey information rather than accurately reproducing the full content of testimony or legal documents. This problem is particularly acute during witness examination, defendant statements, and sight translation of documentary evidence. Summarization or selective omission often results in substantive distortion of meaning.

More troubling still are instances in which interpreters knowingly provide inaccurate interpretations without correction, assuming both the opposing counsel and the court will accept the rendition. In such cases, defendants may end up “hearing what they want to hear” rather than what is actually recorded in the case file. This conduct constitutes a serious breach of professional ethics and exposes interpreters to potential legal liability.

4. Policy and Professional Recommendations

The foregoing analysis shows that relying on government-affiliated interpreters without robust quality-control mechanisms cannot adequately safeguard the right to a fair trial. Suspects and legal counsel should be entitled to select interpreters who meet the following criteria:

(1) demonstrable language proficiency verified through internationally recognized testing;

(2) certification or licensure from a professional interpreting association or regulatory body; and

(3) accountability under a clear code of professional ethics and disciplinary framework.

Attendance certificates or short-term training issued by government agencies should not be misconstrued as equivalent to professional certification or proof of interpreting competence.

Conclusion

Errors in criminal interpretation are not merely linguistic mistakes; they constitute violations of human rights with systemic implications for the administration of justice. Elevating the standards of legal interpreting in Thailand is therefore not solely a professional concern but a state obligation arising from international legal commitments. Restoring long-term public confidence in the justice system requires structural reform and professional accountability.

References

- United Nations. (1966). International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. United Nations Treaty Series, 999, 171.

- Hale, S. B. (2014). Hale (2014) presents a discourse on court interpreting. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Pöchhacker, F. (2016). The book is titled “Introducing interpreting studies (2nd ed.).” Routledge.

- Berk-Seligson, S. (2002). The bilingual courtroom: Court interpreters in the judicial process (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press.

About Certified Translators, Translation Certifiers, and Certified Interpreters of SEAProTI

The Southeast Asian Association of Professional Translators and Interpreters (SEAProTI) has officially shared the qualifications and requirements for becoming Certified Translators, Translation Certification Providers, and Certified Interpreters in Sections 9 and 10 of the Royal Gazette, which was published by the Prime Minister’s Office in Thailand on July 25, 2024. Certified Translators, Translation Certification Providers, and Certified Interpreters

The Council of State has proposed the enactment of a Royal Decree, granting registered translators and recognised translation certifiers from professional associations or accredited language institutions the authority to provide legally valid translation certification (Letter to SEAProTI dated April 28, 2025)

SEAProTI is the first professional association in Thailand and Southeast Asia to implement a comprehensive certification system for translators, certifiers, and interpreters.

Head Office: Baan Ratchakru Building, No. 33, Room 402, Soi Phahonyothin 5, Phahonyothin Road, Phaya Thai District, Bangkok 10400, Thailand

Email: hello@seaproti.com | Tel.: (+66) 2-114-3128 (Office hours: Mon–Fri, 09:00–17:00)

ปัญหาเชิงโครงสร้างของการใช้ล่ามสังกัดหน่วยงานราชการไทยในกระบวนการยุติธรรม:

ผลกระทบต่อสิทธิในการพิจารณาคดีอย่างเป็นธรรมตามมาตรฐานสากล

25 มกราคม 2569, กรุงเทพมหานคร – ล่ามในกระบวนการยุติธรรมมีบทบาทสำคัญอย่างยิ่งในการคุ้มครองสิทธิของผู้ต้องหา จำเลย และพยาน โดยเฉพาะในคดีอาญาที่เกี่ยวข้องกับบุคคลซึ่งไม่สามารถใช้ภาษาไทยได้อย่างมีประสิทธิภาพ หลักการสากลว่าด้วยสิทธิในการพิจารณาคดีอย่างเป็นธรรม (fair trial) กำหนดไว้อย่างชัดเจนว่าบุคคลต้องมีสิทธิได้รับความช่วยเหลือจากล่ามที่มีความสามารถและเป็นอิสระ อย่างไรก็ตาม ในบริบทของประเทศไทย การใช้ล่ามที่สังกัดหน่วยงานราชการยังคงเผชิญปัญหาเชิงโครงสร้างหลายประการ ซึ่งส่งผลกระทบโดยตรงต่อความถูกต้องของกระบวนการยุติธรรมและสิทธิมนุษยชนขั้นพื้นฐาน

บทความนี้มุ่งวิเคราะห์ปัญหาดังกล่าวในสามมิติหลัก ได้แก่ (1) ระดับความสามารถทางภาษาที่ไม่เป็นไปตามมาตรฐานสากล (2) โครงสร้างค่าตอบแทนที่ต่ำผิดสัดส่วนกับความรับผิด และ (3) พฤติกรรมการแปลที่บิดเบือนสาระสำคัญของคำให้การหรือเอกสารในคดี

1. ระดับความสามารถทางภาษากับปัญหาการขึ้นทะเบียนล่ามของรัฐ

แม้ล่ามของหน่วยงานราชการไทยจำนวนหนึ่งจะผ่านกระบวนการ “ขึ้นทะเบียน” อย่างเป็นทางการ แต่การขึ้นทะเบียนดังกล่าวมิได้มาพร้อมกับการเปิดเผยหรือยืนยันผลสอบวัดระดับภาษาในมาตรฐานสากล เช่น CEFR, IELTS, TOEFL หรือการสอบเฉพาะทางด้านล่ามกฎหมาย การขาดกลไกตรวจสอบเชิงคุณภาพนี้ส่งผลให้ล่ามจำนวนไม่น้อยมีระดับความสามารถทางภาษาที่ไม่เพียงพอสำหรับการปฏิบัติงานในคดีที่มีความซับซ้อน

ปัญหานี้ขัดแย้งโดยตรงกับหลักการตามกติการะหว่างประเทศว่าด้วยสิทธิพลเมืองและสิทธิทางการเมือง (ICCPR) ซึ่งประเทศไทยเป็นภาคีภายใต้กรอบของ องค์การสหประชาชาติ โดยเฉพาะบทบัญญัติที่รับรองสิทธิของผู้ต้องหาในการได้รับการแปลและการล่าม “อย่างเพียงพอและมีประสิทธิภาพ” (adequate and effective interpretation) ไม่ใช่เพียงการมีล่ามในเชิงรูปแบบเท่านั้น

2. โครงสร้างค่าตอบแทนที่ต่ำและแรงจูงใจเชิงลบในทางปฏิบัติ

โครงสร้างค่าตอบแทนของล่ามสังกัดหน่วยงานราชการในประเทศไทยอยู่ในระดับที่ต่ำมากเมื่อเทียบกับภาระความรับผิดและความเสี่ยงทางวิชาชีพ โดยในหลายพื้นที่ชายแดน ค่าตอบแทนล่ามอยู่เพียงประมาณ 300–500 บาทต่อวัน และในคดีสำคัญอาจเพิ่มขึ้นแต่ยังไม่เกิน 4,200 บาทต่อวัน

เมื่อเปรียบเทียบกับภาคเอกชน ซึ่งค่าตอบแทนล่ามกฎหมายเริ่มต้นที่ประมาณ 6,000 บาทต่อวัน และอาจสูงถึง 10,000–25,000 บาทต่อวันในคดีอนุญาโตตุลาการหรือคดีข้ามชาติ จะเห็นได้ว่าความเหลื่อมล้ำด้านค่าตอบแทนนี้สร้างแรงจูงใจเชิงลบอย่างมีนัยสำคัญ ในทางปฏิบัติ มีข้อร้องเรียนและประสบการณ์ภาคสนามที่สะท้อนว่าล่ามบางรายเรียกรับเงินเพิ่มเติมจากพยานหรือผู้ต้องหาชาวต่างชาติในช่วงที่ไม่มีการกำกับดูแลจากศาลหรือเจ้าหน้าที่ ซึ่งบ่อนทำลายความเป็นกลางและความน่าเชื่อถือของกระบวนการยุติธรรมโดยตรง

3. การแปลแบบสรุปและการบิดเบือนความหมายในกระบวนพิจารณา

หนึ่งในปัญหาที่ร้ายแรงที่สุดคือการที่ล่ามซึ่งมีความสามารถจำกัดใช้วิธี “การแปลแบบสรุป” แทนการถ่ายทอดสารอย่างครบถ้วนและแม่นยำ โดยเฉพาะในขั้นตอนการซักถาม การให้การ และการแปลเอกสารในลักษณะ sight translation การสรุปหรือเลือกถ่ายทอดเพียงบางส่วนทำให้สาระสำคัญของคำให้การผิดเพี้ยนไปจากต้นฉบับ

ยิ่งไปกว่านั้น ในบางกรณีล่ามตระหนักดีว่าตนแปลผิด แต่เลือกไม่แก้ไข เนื่องจากทราบว่าทนายฝ่ายตรงข้ามหรือศาลอาจไม่ทักท้วง ส่งผลให้เกิดการบิดเบือนความหมายเชิงเนื้อหา และทำให้ผู้ต้องหา “ได้ยินในสิ่งที่ตนอยากได้ยิน” มากกว่าสิ่งที่ปรากฏในสำนวนคดี พฤติกรรมดังกล่าวไม่เพียงเป็นการละเมิดจริยธรรมวิชาชีพ แต่ยังเปิดช่องให้เกิดความรับผิดทางกฎหมายต่อล่ามในภายหลัง

4. ข้อเสนอเชิงนโยบายและเชิงวิชาชีพ

จากการวิเคราะห์ข้างต้น การใช้ล่ามสังกัดหน่วยงานราชการโดยปราศจากกลไกควบคุมคุณภาพที่เข้มแข็งไม่อาจรับประกันสิทธิในการพิจารณาคดีอย่างเป็นธรรมได้ ผู้ต้องหาและทนายความควรมีสิทธิเลือกใช้ล่ามที่มีคุณสมบัติดังต่อไปนี้

(1) มีผลสอบวัดระดับภาษาที่เป็นที่ยอมรับในระดับสากล

(2) ได้รับการรับรองหรือมีใบอนุญาตจากองค์กรหรือสมาคมวิชาชีพล่าม

(3) อยู่ภายใต้จรรยาบรรณและระบบความรับผิดทางวิชาชีพที่ชัดเจน

การมี “ใบประกาศการอบรม” จากหน่วยงานราชการไม่ควรถูกตีความว่าเทียบเท่ากับการรับรองความสามารถทางวิชาชีพ

บทสรุป

การแปลผิดในคดีอาญาไม่ใช่เพียงความผิดพลาดทางภาษา แต่เป็นการละเมิดสิทธิมนุษยชนที่มีผลกระทบเชิงโครงสร้างต่อความยุติธรรมของสังคม การยกระดับมาตรฐานล่ามในกระบวนการยุติธรรมไทยจึงไม่ใช่เรื่องของวิชาชีพเพียงอย่างเดียว หากแต่เป็นพันธกิจของรัฐในการปฏิบัติตามพันธกรณีระหว่างประเทศและสร้างความเชื่อมั่นต่อระบบยุติธรรมในระยะยาว

เอกสารอ้างอิง

- United Nations. (1966). International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. United Nations Treaty Series, 999, 171.

- Hale, S. B. (2014). The discourse of court interpreting. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Pöchhacker, F. (2016). Introducing interpreting studies (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Berk-Seligson, S. (2002). The bilingual courtroom: Court interpreters in the judicial process (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press.

เกี่ยวกับนักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรองของสมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้

สมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ (SEAProTI) ได้ประกาศหลักเกณฑ์และคุณสมบัติของผู้ที่ขึ้นทะเบียนเป็น “นักแปลรับรอง (Certified Translators) และผู้รับรองการแปล (Translation Certification Providers) และล่ามรับรอง (Certified Interpreters)” ของสมาคม หมวดที่ 9 และหมวดที่ 10 ในราชกิจจานุเบกษา ของสำนักเลขาธิการคณะรัฐมนตรี ในสำนักนายกรัฐมนตรี แห่งราชอาณาจักรไทย ลงวันที่ 25 ก.ค. 2567 เล่มที่ 141 ตอนที่ 66 ง หน้า 100 อ่านฉบับเต็มได้ที่: นักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรอง

สำนักคณะกรรมการกฤษฎีกาเสนอให้ตราเป็นพระราชกฤษฎีกา โดยกำหนดให้นักแปลที่ขึ้นทะเบียน รวมถึงผู้รับรองการแปลจากสมาคมวิชาชีพหรือสถาบันสอนภาษาที่มีการอบรมและขึ้นทะเบียน สามารถรับรองคำแปลได้ (จดหมายถึงสมาคม SEAProTI ลงวันที่ 28 เม.ย. 2568)

สมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ เป็นสมาคมวิชาชีพแห่งแรกและแห่งเดียวในประเทศไทยและภูมิภาคเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ที่มีระบบรับรองนักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรอง

สำนักงานใหญ่: อาคารบ้านราชครู เลขที่ 33 ห้อง 402 ซอยพหลโยธิน 5 ถนนพหลโยธิน แขวงพญาไท เขตพญาไท กรุงเทพมหานคร 10400 ประเทศไทย

อีเมล: hello@seaproti.com โทรศัพท์: (+66) 2-114-3128 (เวลาทำการ: วันจันทร์–วันศุกร์ เวลา 09.00–17.00 น.