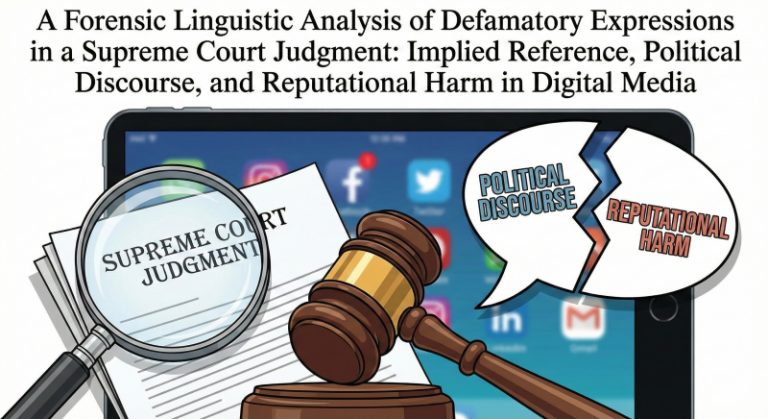

Forensic Linguistic Analysis of the Thai Prime Minister’s Statement

Regarding the Leaked Audio of a Conversation with Samdech Hun Sen

Author: Wanitcha Sumanat, president of the Southeast Asian Association of Professional Translators and Interpreters

16 August 2025, Bangkok – The leaked audio of a telephone conversation between the Thai Prime Minister and Samdech Hun Sen, President of the Cambodian Senate, on June 15, 2025, sparked intense political debate and legal controversy in Thailand. This case not only reflects the complexities of Thai–Cambodian border relations but also underscores the importance of interpreting language and the use of linguistic evidence in political and constitutional adjudication. This article analyzes the Prime Minister’s statement through the framework of forensic linguistics to evaluate linguistic strategies, interpretive implications, and the expected outcomes of submitting such a statement before the Constitutional Court of Thailand.

Narrative Structure and Temporal Management

The statement was constructed as a “narrative” with sequential ordering of events: the JBC meeting, the phone call through Mr. Huad, the national security meeting, and the leak of the audio file. This sequencing was intended to frame the Prime Minister not as the initiator but as one responding to situational necessity. The use of terms such as “compelled to” and “deemed appropriate” demonstrates agency management that downplays personal responsibility by shifting agency to others or external circumstances (Coulthard & Johnson, 2010).

However, discrepancies in the reported years (2015/2021/2025) constitute temporal inconsistencies that could undermine credibility as documentary evidence if not corrected (Olsson, 2008).

Pragmatics and Politeness Strategies

From a pragmatic perspective, the use of the term “uncle” was explained as a cultural term of respect in Thai society, not as a derogation of the Cambodian leader’s status. This aligns with positive politeness theory by Brown and Levinson (1987), which emphasizes face-saving strategies in conflictual contexts.

The phrase “Tell me what you want, and I will arrange it” was reframed as a principled negotiation technique aimed at eliciting true interests of the interlocutor (Fisher, Ury, & Patton, 2011), rather than a willingness to trade national interests. This demonstrates an “interpretive contest” between the petitioner’s reading (implying concession) and the respondent’s framing (a negotiation probe).

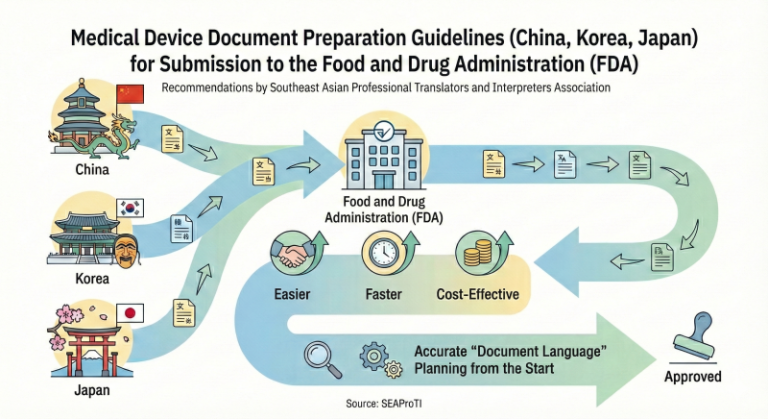

Evidentiality and Undermining the Audio Evidence

The respondent highlighted that the leaked audio had not been officially translated and certified by registered interpreters and was illegally obtained under the 2007 Computer Crime Act. This connects directly to evidentiary standards in court, which typically exclude illegally obtained evidence (Gibbons, 2003; Shuy, 2005). The insistence on certified interpreters aligns with Hale (2004) and Wadensjö (1998), who emphasized that legal translation requires attention not only to lexical fidelity but also to pragmatic and contextual accuracy.

Strategic Implications for Court Proceedings

Strengths of the Statement

- Good Faith Framing: Negotiation framed as serving the national interest, not personal gain, aligning with constitutional principles of integrity.

- Undermining Petitioner’s Evidence: By arguing improper acquisition and uncertified translation, the court may hesitate to admit the audio as full evidence.

- Political Question Doctrine: Emphasis that foreign affairs are political matters, not strictly judicial ones (Eades, 2010).

Risks

- Temporal inconsistencies may allow challenges to credibility.

- Problematic phrases such as “uncle” and “Tell me what you want…” remain risky if interpreted literally and supported by a credible transcript.

- Shifting responsibility to Mr. Huad reduces agency but raises questions about state-level communication security.

Intended Outcomes of the Statement

The main persuasive goal is to diminish the probative value of the audio evidence and reframe the controversial phrases within the context of “peace diplomacy” rather than “trading away national interests.” The statement also emphasizes that all actions were conducted in good faith and should be judged within the political—not judicial—domain.

If the court accepts this framing, the expected outcome is that the Prime Minister will retain office and safeguard governmental stability amid border tensions.

Executive Summary

- This clarification constructs a defensive narrative intended to mitigate the weight of allegations before the court. It advances four central arguments: (1) the actions in question were undertaken in good faith and for the public interest, not personal gain; (2) the conversations were informal exchanges, not binding legal or diplomatic commitments; (3) the audio recording, transcript, and translation are unreliable, having been improperly obtained and not subjected to proper verification; and (4) the matter constitutes a political question more appropriately examined by parliamentary oversight than by judicial intervention.

- Linguistically, the statement employs several strategic devices: agency management to minimize the speaker’s role in initiating events; politeness and mitigation to soften tone and reduce confrontational impact; evidentiality to draw on institutional and procedural references for credibility; and the reframing of the phrase “If you want anything, just tell me” as an instance of Principled Negotiation, emphasizing cooperation and problem-solving rather than submission or binding obligation.

- Potential vulnerabilities remain. Temporal inconsistencies in references to years (2015, 2021, 2025) create “linguistic scars of time” that may undermine credibility. In addition, pragmatic expressions such as “uncle” and “If you want anything, just tell me” could still carry negative image impacts, suggesting undue closeness or implied commitments when considered alongside the audio and translation.

- The ultimate effect depends on the court’s assessment of evidence’s credibility. If the clip–transcript–translation triad is deemed unreliable, the allegations weaken substantially. If considered accurate, cultural and diplomatic explanations may mitigate but not eliminate their impact. Overall, the statement strategically frames the case as informal, good-faith, and political rather than judicial, using rhetorical tools to reshape interpretation and lessen the legal force of the allegations.

Forensic Recommendations for Enhancing Credibility

- Audio Forensics: Authenticity verification, metadata, and chain of custody.

- Bilingual Aligned Transcript: Time-aligned bilingual transcript with confidence scores and ambiguity notes.

- Independent Translation Panel: Certified legal interpreters producing blind translations with adjudicated consensus.

- Pragmatics Report: Contextual explanation of problematic phrases within Thai politeness/diplomatic norms.

- Timeline Matrix: Cross-checked logs of meetings, calls, and orders to correct chronological inconsistencies.

- Cultural–Diplomatic Norms: Institutional documents confirming the acceptability of informal crisis diplomacy.

Court-Level Conclusion

If the court excludes or limits the leaked audio due to procedural flaws or uncertified translation, the framing of good faith diplomacy without binding commitments will likely prevail, making it difficult to justify removal from office. If the audio is admitted with full weight, pragmatic explanations may soften but not fully neutralize reputational concerns. The court’s choice of interpretive standards will ultimately determine the Prime Minister’s political fate.

References

- Berk-Seligson, S. (2009). Coerced confessions: The discourse of bilingual police interrogations. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Brown, P., & Levinson, S. C. (1987). Politeness: Some universals in language usage. Cambridge University Press.

- Coulthard, M., & Johnson, A. (2010). An introduction to forensic linguistics: Language in evidence (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Coulthard, M., May, A., & Johnson, A. (Eds.). (2017). The Routledge handbook of forensic linguistics. Routledge.

- Eades, D. (2010). Sociolinguistics and the legal process. Multilingual Matters.

- Fisher, R., Ury, W., & Patton, B. (2011). Getting to yes: Negotiating agreement without giving in (3rd ed.). Penguin.

- Gibbons, J. (2003). Forensic linguistics: An introduction to language in the justice system. Blackwell.

- Hale, S. (2004). The discourse of court interpreting: Discourse practices of the law, the witness, and the interpreter. John Benjamins.

- Jessen, M. (2008). Forensic phonetics. Language and Linguistics Compass, 2(4), 671–711.

- Mason, I. (Ed.). (2009). The translator as communicator. Routledge.

- Olsson, J. (2008). Forensic linguistics: An introduction to language, crime and the law (2nd ed.). Continuum.

- Shuy, R. (2005). Creating language crimes: How law enforcement uses (and misuses) language. Oxford University Press.

- Solan, L. M., & Tiersma, P. M. (2005). Speaking of crime: The language of criminal justice. University of Chicago Press.

- Wadensjö, C. (1998). Interpreting as interaction. Longman.

About Certified Translators, Translation Certification Providers, and Certified Interpreters of SEAProTI

The Southeast Asian Association of Professional Translators and Interpreters (SEAProTI) has published the criteria and qualifications for registering as “Certified Translators,” “Translation Certification Providers,” and “Certified Interpreters” of the Association under Sections 9 and 10 of the Royal Gazette, Secretariat of the Cabinet, Prime Minister’s Office, Kingdom of Thailand, dated 25 July 2024, Vol. 141, Part 66 Ng, p. 100. Full text available at: The Royal Thai Government Gazette

SEAProTI is the first professional association in Thailand and Southeast Asia with a formal certification system for Certified Translators, Translation Certification Providers, and Certified Interpreters.

Head Office: Baan Ratchakhru Building, No. 33, Room 402, Soi Phahonyothin 5, Phahonyothin Road, Phaya Thai Subdistrict, Phaya Thai District, Bangkok 10400, Thailand. Email: hello@seaproti.com Tel: (+66) 2-114-3128 (Office hours: Mon–Fri, 9:00–17:00)

การวิเคราะห์ทางนิติภาษาศาสตร์ของถ้อยคำชี้แจงนายกรัฐมนตรีไทยต่อกรณีคลิปเสียงการสนทนากับสมเด็จฮุน เซน

ผู้แต่ง วณิชชา สุมานัส นายกสมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้

16 สิงหาคม 2568, กรุงเทพมหานคร – เหตุการณ์การเผยแพร่คลิปเสียงการสนทนาทางโทรศัพท์ระหว่างนายกรัฐมนตรีไทยกับสมเด็จฮุน เซน ประธานวุฒิสภากัมพูชา เมื่อวันที่ 15 มิถุนายน 2568 ได้สร้างกระแสการเมืองและข้อถกเถียงทางกฎหมายอย่างกว้างขวางในประเทศไทย กรณีดังกล่าวไม่เพียงสะท้อนถึงความซับซ้อนของความสัมพันธ์ชายแดนไทย–กัมพูชา แต่ยังชี้ให้เห็นถึงความสำคัญของ การตีความถ้อยคำ และ การใช้พยานหลักฐานภาษา ในกระบวนการพิจารณาคดีทางการเมืองและรัฐธรรมนูญ บทความนี้มุ่งวิเคราะห์ถ้อยคำชี้แจงของนายกรัฐมนตรีผ่านกรอบ นิติภาษาศาสตร์ (forensic linguistics) เพื่อประเมินยุทธศาสตร์ทางภาษา ผลกระทบเชิงการตีความ และความคาดหวังผลลัพธ์จากการยื่นคำชี้แจงต่อศาลรัฐธรรมนูญ

โครงสร้างเรื่องเล่าและการจัดการเวลา

คำชี้แจงถูกเรียบเรียงให้เป็น “โครงเรื่อง” (narrative structure) ที่มีการลำดับเหตุการณ์อย่างเป็นขั้นตอน ตั้งแต่การประชุม JBC การโทรศัพท์ผ่านนายฮวด การประชุมฝ่ายความมั่นคง และการเผยแพร่คลิปเสียง โดยทั้งหมดถูกเชื่อมโยงเพื่อสร้างภาพว่า นายกรัฐมนตรีไม่ได้เป็นผู้ริเริ่มการติดต่อ แต่เป็นการตอบสนองต่อสถานการณ์เฉพาะหน้า การใช้ถ้อยคำว่า “จำต้อง”, “เห็นสมควร” แสดงถึงการจัดการ “agency” เพื่อลดบทบาทการกระทำของตนเอง และโยกย้ายความรับผิดไปที่บุคคลอื่นหรือสถานการณ์ (Coulthard & Johnson, 2010)

อย่างไรก็ดี การคลาดเคลื่อนของปี พ.ศ. (2558/2564/2568) ที่ปรากฏในบางช่วง ถือเป็น ร่องรอยความไม่สอดคล้องด้านเวลา (temporal inconsistencies) ที่อาจกระทบต่อความน่าเชื่อถือในเชิงพยานเอกสาร หากไม่ได้รับการแก้ไขหรือตรวจสอบ (Olsson, 2008)

วัจนปฏิบัติและกลยุทธ์ความสุภาพ

ในเชิงวัจนปฏิบัติ คำว่า “uncle” ถูกอธิบายว่าเป็นการใช้สรรพนามทางวัฒนธรรมไทยเพื่อแสดงความเคารพ ไม่ใช่การลดทอนสถานะผู้นำประเทศคู่กรณี การตีความนี้สอดคล้องกับทฤษฎี ความสุภาพเชิงบวก (positive politeness) ของ Brown และ Levinson (1987) ที่มุ่งรักษาหน้าคู่สนทนาในสถานการณ์ความขัดแย้ง

วลี “อยากได้อะไรก็บอกมา เดี๋ยวจะจัดการให้” ถูกกรอบความหมายใหม่ให้เป็น เทคนิคการเจรจาเชิงผลประโยชน์ (principled negotiation) ที่ตั้งคำถามเพื่อค้นหาความต้องการที่แท้จริงของคู่เจรจา (Fisher, Ury, & Patton, 2011) ไม่ใช่การยอมแลกเปลี่ยนผลประโยชน์ของชาติ การตีความนี้เป็นความพยายาม “ช่วงชิงความหมาย” (interpretive contest) ระหว่างฝ่ายร้องและฝ่ายถูกร้อง

การอ้างหลักฐานและการลดน้ำหนักพยานคลิปเสียง

ผู้แถลงชี้ให้เห็นว่าคลิปเสียงดังกล่าว ยังไม่ผ่านการแปลและการรับรองโดยล่ามขึ้นทะเบียน และเป็นหลักฐานที่ได้มาโดยมิชอบตามพระราชบัญญัติคอมพิวเตอร์ พ.ศ. 2550 ประเด็นนี้สัมพันธ์โดยตรงกับมาตรฐานการรับฟังพยานในศาลที่มักปฏิเสธ พยานที่ได้มาโดยไม่ชอบด้วยกฎหมาย (Gibbons, 2003; Shuy, 2005) การยืนยันให้แปลโดยผู้เชี่ยวชาญที่ขึ้นทะเบียนอย่างเป็นทางการ สอดคล้องกับข้อเสนอของ Hale (2004) และ Wadensjö (1998) ที่ชี้ว่าการตีความและการแปลในบริบททางกฎหมายต้องคำนึงถึงทั้งถ้อยคำและบริบทเชิงปฏิบัติการ

ผลทางยุทธศาสตร์ต่อการพิจารณาของศาล

จุดแข็งของถ้อยคำชี้แจง

- กรอบความสุจริตใจ: เน้นว่าเจรจาเพื่อผลประโยชน์ของชาติ มิใช่เพื่อประโยชน์ส่วนตน → สอดคล้องกับมาตรา 164 รัฐธรรมนูญว่าด้วย “หลักสุจริต”

- ลดน้ำหนักพยานฝ่ายร้อง: อ้างว่าคลิปเสียงไม่ได้มาตามกระบวนการ → ศาลอาจลังเลที่จะรับฟังเต็มน้ำหนัก

- Political Question Doctrine: ชี้ว่ากิจการต่างประเทศควรตรวจสอบโดยกลไกการเมืองมากกว่าทางตุลาการ (Eades, 2010)

จุดเสี่ยง

- ความคลาดเคลื่อนทางเวลา → เปิดช่องให้ถูกท้าทายด้านความน่าเชื่อถือ

- วลี “uncle” และ “อยากได้อะไร…” → แม้ตีความได้หลายแบบ แต่ยังเสี่ยงหากศาลให้น้ำหนักการแปลตรงตัว

- การโยกภาระไปที่ “นายฮวด” → ช่วยลดความรับผิด แต่สะท้อนถึงความบกพร่องของระบบความมั่นคงสารสนเทศของฝ่ายไทยเอง

การตีความว่าผู้แถลงหวังผลอย่างไร

การชี้แจงดังกล่าวมีเป้าหมายหลักคือ ทำให้ศาลลดน้ำหนักการพิจารณาคลิปเสียง และตีความถ้อยคำที่มีปัญหาในกรอบของ “การเจรจาเพื่อสันติ” มากกว่าการ “ยอมแลกเปลี่ยนผลประโยชน์ของชาติ” พร้อมทั้งวางโครงเรื่องว่า ทุกการกระทำเป็นไปโดยสุจริตใจ และควรถูกพิจารณาในเชิงการเมืองมากกว่าการลงโทษทางจริยธรรมร้ายแรง

หากศาลยอมรับกรอบนี้ ผลลัพธ์ที่ผู้แถลงคาดหวังคือ การไม่หยุดปฏิบัติหน้าที่นายกรัฐมนตรี และการรักษาความมั่นคงทางการเมืองของรัฐบาลในห้วงวิกฤตชายแดน

สรุปย่อ (Executive Summary)

- ข้อความชี้แจงนี้ถูกสร้างขึ้นในลักษณะของ เรื่องเล่าเชิงป้องกันตัว (defensive narrative) โดยมีเป้าหมายเพื่อลดน้ำหนักของข้อกล่าวหาในสายตาศาล โดยมีข้อโต้แย้งหลัก 4 ประการ ได้แก่ (1) การกระทำดังกล่าวเป็นไปด้วยความสุจริตและเพื่อประโยชน์สาธารณะ มิใช่เพื่อผลประโยชน์ส่วนตน, (2) การสนทนาเป็นเพียงการแลกเปลี่ยนอย่างไม่เป็นทางการ มิได้ก่อให้เกิดพันธกรณีทางกฎหมายหรือการทูต, (3) พยานหลักฐานซึ่งประกอบด้วยคลิปเสียง ถอดความ และคำแปล ไม่อาจเชื่อถือได้ เนื่องจากได้มาโดยไม่ชอบและยังไม่ได้ผ่านการตรวจสอบความถูกต้องอย่างเป็นทางการ, และ (4) ประเด็นดังกล่าวเป็น คำถามเชิงการเมือง (political question) ที่เหมาะสมต่อการตรวจสอบโดยกลไกรัฐสภามากกว่าการพิจารณาโดยศาล

- ในเชิงภาษาศาสตร์ ข้อความชี้แจงนี้ใช้ กลยุทธ์ทางภาษา หลายประการ ได้แก่ การจัดการอำนาจในตน (agency management) เพื่อลดบทบาทของผู้พูดในฐานะผู้ริเริ่มเหตุการณ์, การใช้ความสุภาพและการลดแรงปะทะ (politeness and mitigation) เพื่อลดโทนเผชิญหน้า, การอ้างหลักฐานเชิงสถาบัน (evidentiality) โดยเชื่อมโยงกับหน่วยงานและกระบวนการเพื่อเสริมสร้างความน่าเชื่อถือ, และการตีความวลี “อยากได้อะไรก็บอกมา” ในฐานะตัวอย่างของการเจรจาเชิงหลักการ (Principled Negotiation) ที่เน้นความร่วมมือและการแก้ปัญหา มากกว่าการยอมจำนนหรือการผูกพันเชิงอำนาจ

- อย่างไรก็ดี ยังมี ความเสี่ยงที่อาจถูกโจมตีได้ ได้แก่ ความไม่สอดคล้องกันของปีที่อ้างถึง (พ.ศ. 2558, 2564, 2568) ซึ่งก่อให้เกิด “รอยนิรุกติศาสตร์แห่งเวลา” (linguistic scars of time หรือ temporal inconsistencies) ที่อาจบ่อนทำลายความน่าเชื่อถือของเอกสาร อีกทั้งวลีเชิงปฏิบัติ เช่น “uncle” และ “อยากได้อะไรก็บอกมา” แม้จะสามารถอธิบายว่าเป็นมารยาททางวัฒนธรรมหรือการทูต แต่ก็ยังอาจส่งผลกระทบทางภาพลักษณ์ โดยสื่อถึงความใกล้ชิดส่วนตัวหรือการให้คำมั่นโดยนัย เมื่อพิจารณาควบคู่กับเสียงบันทึกและคำแปล

- ผลลัพธ์สุดท้ายขึ้นอยู่กับการประเมินของศาลต่อความน่าเชื่อถือของ คลิป–ถอดความ–คำแปล หากถูกตัดสินว่าไม่น่าเชื่อถือ ข้อกล่าวหาจะอ่อนแรงลงอย่างมาก แต่หากถือว่าน่าเชื่อถือ คำอธิบายเชิงวัฒนธรรมและการทูตอาจบรรเทาผลกระทบได้บ้าง แต่ไม่สามารถลบล้างได้ทั้งหมด โดยสรุป ข้อความชี้แจงนี้เป็นการจัดวางกรอบเชิงกลยุทธ์ให้คดีถูกมองว่าเป็นเรื่อง ไม่เป็นทางการ สุจริต และควรอยู่ในมิติการเมืองมากกว่ามิติการพิจารณาของศาล อันเป็นการใช้เครื่องมือทางวาทกรรมเพื่อปรับทิศทางการตีความและลดทอนแรงกดทางกฎหมายของข้อกล่าวหา

วิธีวิเคราะห์ (Method)

- วิเคราะห์ถ้อยคำและโครงสร้างเรื่องเล่า (narrative & discourse structure)

- วิเคราะห์วัจนปฏิบัติ (speech acts), กลยุทธ์ความสุภาพ/การลดแรงปะทะ (politeness/mitigation), ภาวะพหุเสียง (intertextuality/evidentiality)

- วิเคราะห์ข้ามภาษา (cross-linguistic pragmatics) ต่อประเด็น “uncle”, “อยากได้อะไรก็บอกมา…”, และการกล่าวถึงแม่ทัพภาคที่ 2

- ประเมินความสอดคล้องด้านเวลา/เหตุการณ์ (temporal & event alignment) และผลต่อความน่าเชื่อถือ

- วางผลการวิเคราะห์ลงในกรอบมาตรฐานการรับฟังพยานภาษา/เสียง: ความแท้จริงของไฟล์, ความถูกต้องของการถอด–แปล, และห่วงโซ่พยาน (chain of custody)

ประเด็นนิติภาษาศาสตร์ที่พบ

1) โครงเรื่องเล่าและการจัดวางเวลา (Narrative & Temporal Alignment)

- เอกสารเน้นลำดับเหตุ–ผล: “เหตุปะทุ–ข้อเสนอให้ ‘เย็นลง’–พยายามโทร–ไม่ได้รับ–เย็นวันนั้นจึงเกิด conference call–สรุปแจ้งฝ่ายมั่นคง–ตั้งทีม–ฝ่ายตรงข้ามเผยแพร่คลิป–ขอโทษ–ย้ำเอกภาพ” → เป็น story-arc แบบ “crisis management”

- พบ “ความคลาดเคลื่อนปี พ.ศ.” หลายจุด (เช่น 2558/2564/2568) ซึ่งในเชิงนิติภาษาศาสตร์ถือเป็น “inconsistency markers” ที่ศาลหรือคู่ความอาจใช้ตั้งคำถามต่อความประณีตของการเรียบเรียง/แก้ไขฉบับร่าง และอาจบั่นทอน ethos ของผู้แถลง แม้มิได้ทำลายสาระเนื้อหาโดยตรง

2) การจัดการภาพตัวการ (Agency Management)

- การย้ำว่า “มิได้เป็นผู้ริเริ่มโทร” และ “เป็นสถานการณ์เฉพาะหน้า” เป็นเทคนิคเลื่อนศูนย์ถ่วงความรับผิด (shifting agency) จากตนสู่ “นายฮวด”/ปัจจัยภายนอก เพื่อลดการอนุมานเจตนาเจรจาลับ

- การใช้กริยาช่วย/โครงสร้างบอกจำเป็น (“จำต้อง”, “เห็นสมควรให้…เข้าพบ”) ลดเจตจำนงเชิงรุกของตน → สอดคล้องกับวาทกรรม “ภาวะจำเป็นของผู้นำในวิกฤต”

3) ความสุภาพ–การลดแรงปะทะ (Politeness & Mitigation)

- คำว่า “uncle” ถูกจัดกรอบเป็นประเพณีสังคมไทย/การทูตไม่เป็นทางการ → ตามทฤษฎีความสุภาพของ Brown & Levinson คือกลยุทธ์รักษาหน้าคู่เจรจา (positive politeness) ในสถานการณ์ความขัดแย้ง

- การกล่าวขอโทษต่อแม่ทัพภาคที่ 2 และรายงานว่า “คู่กรณีไม่ติดใจ” เป็นการซ่อมแซมความสัมพันธ์เชิงสถาบัน (relationship repair) ลดภาพ “แตกแยก” รัฐ–ทหาร

4) วัจนปฏิบัติของวลีเสี่ยง

- “อยากได้อะไรก็บอกมา…เดี๋ยวจะจัดการให้” ถูกตีความใหม่ว่าเป็น “คำถามเพื่อค้นหาผลประโยชน์แท้จริง” (interest-based move) ตามแนว Fisher, Ury & Patton มากกว่าคำมั่นแลกเปลี่ยนผลประโยชน์ → เป็นการต่อสู้เชิงการตีความ (interpretive contest) ระหว่าง “คำมั่นยอมอ่อนข้อ” กับ “เทคนิคสืบค้นจุดยืน–ผลประโยชน์”

- หากศาลยอมรับกรอบนี้ น้ำหนักเชิงลบของวลีจะลดลง แต่ถ้าศาลยึดการอ่านตรงตัว/พยานแปล–ถอดเสียงที่น่าเชื่อถือ วลีนี้ยังสร้างแรงกระแทกภาพลักษณ์ได้

5) การอ้างหลักฐาน/พยานสถาบัน (Evidentiality)

- การอ้างชื่อผู้เข้าประชุม, หน่วยงาน, เอกสารแนบท้าย, คำสั่งปิดด่าน ฯลฯ ทำหน้าที่สร้าง “ร่องรอยสถาบัน” (institutional footprints) เพื่อหนุนข้อเท็จจริงและเจตนาบริสุทธิ์

- ขณะเดียวกัน ผู้แถลงพยายามบ่อนน้ำหนักคลิปด้วยเหตุ “ได้มาไม่ชอบ/ยังไม่แปลรับรอง” ซึ่งเป็นข้อถกเถียงด้านกระบวนวิธีมากกว่าสาระ (substance)

6) มิติสองภาษาและความเสี่ยงการแปล (Bilingual Risks)

- ผู้แถลงขอให้ “ล่ามขึ้นทะเบียนอย่างเป็นทางการ” แปลและให้รัฐทั้งสองฝ่ายรับรอง → ตรงตามข้อเสนอแนะเชิงนิติภาษาศาสตร์ว่าศาลควรประเมิน “ความถูกต้องเชิงถ้อยคำ–เชิงปริบท–เชิงปฏิบัติการ” (lexical, contextual, pragmatic accuracy) ไม่ใช่เพียงคำต่อคำ

- ประเด็น “ลดโทน/เสริมความหมาย” ในการล่าม–แปล (เช่น softening, insertion/omission) ควรถูกตรวจโดยการทำ “bilingual aligned transcript” คู่กับไฟล์เสียง โดยผู้เชี่ยวชาญเป็นอิสระหลายฝ่าย (inter-rater reliability)

ผลทางยุทธศาสตร์ต่อการพิจารณาของศาล

จุดแข็งเชิงโน้มน้าว

- กรอบสุจริต–ประโยชน์สาธารณะ: วางเจตนาเพื่อคลี่คลายความตึงเครียด ลดการสูญเสีย → สอดรับมาตรฐาน “good faith” ทางการเมือง/การทูต

- ไม่เป็นทางการ/ไม่ก่อพันธกรณีรัฐ: สนทนากับประธานวุฒิสภากัมพูชา มิใช่ฝ่ายบริหาร และไม่มีการยอมรับเงื่อนไขเป็นลายลักษณ์อักษร

- โจมตีความน่าเชื่อถือพยานฝ่ายร้อง: เน้น “ได้มาไม่ชอบ–ยังไม่แปลรับรอง–ขาด chain of custody” ลดน้ำหนักพยานเสียง/แปล

- Political Question: ชี้ว่ากิจการต่างประเทศโดยสันติวิธีควรถูกตรวจทางการเมืองมากกว่า → ลดการขยายอำนาจพิจารณาของศาลลงสู่ “เหตุผลนโยบาย”

จุดเสี่ยง/จุดอ่อน

- ความคลาดเคลื่อนปี พ.ศ.: ทำให้ฝ่ายตรงข้ามมีพื้นที่ตั้งคำถามต่อความน่าเชื่อถือ/ความพิถีพิถันของคำชี้แจง

- วลีที่ตีความตรงตัวได้เสียหาย: “uncle”, “อยากได้อะไรก็…” แม้มีกรอบอธิบาย แต่ถ้าศาลให้น้ำหนักคลิป–คำแปลสูง กรอบดังกล่าวอาจไม่พอ

- พึ่งพาความเห็น–เจตนาฝ่ายตรงข้าม: การอธิบายแรงจูงใจของอีกฝ่าย (เช่น ฮุน เซน ไม่พอใจ/เล่นการเมือง) อยู่บนฐาน “การคาดการณ์” ซึ่งมีน้ำหนักเชิงพิสูจน์จำกัด

- การย้ายศูนย์ถ่วงไปที่ “นายฮวด”: ช่วยลดเจตนา แต่ก็ทำให้เกิดคำถามใหม่เรื่องการควบคุมช่องทางสื่อสารระดับผู้นำและมาตรฐานความมั่นคงสารสนเทศของฝ่ายไทย

ผู้แถลง “หวังผล” อะไร (Inferred Persuasive Aims)

- Procedural Safe Harbor: ทำให้ศาลลังเลที่จะรับฟัง/ให้น้ำหนักคลิปและคำแปล (exclude or down-weight)

- Framing Substantive Conduct: ให้เห็นว่าเป็น การทูตเพื่อสันติ ไม่ใช่ การต่อรองผลประโยชน์ส่วนตน

- Shift to Political Forum: ชวนให้ตีความว่าเป็นเรื่อง “การเมืองการต่างประเทศ” มากกว่า “จริยธรรมร้ายแรงที่ศาลต้องตัดสินเชิงลงโทษ”

- Display State Cohesion: แสดงความเป็นเอกภาพกับฝ่ายความมั่นคงเพื่อลดภาพ “รัฐแตกแยก”

- Preempt Reputational Harm: ซ่อมแซมภาพคำพูดที่เป็นปัญหาด้วยกรอบวัจนปฏิบัติและวัฒนธรรม

คำแนะนำเชิงนิติภาษาศาสตร์ เพื่อเสริมความน่าเชื่อถือของ “เวอร์ชันเหตุการณ์”

หากจะยื่นเสริมต่อศาล/ตั้งรับการซักถาม ควรเตรียม:

- Audio Forensics: ตรวจสอบความแท้จริงของไฟล์คลิปเสียง (authenticity), การตัดต่อ/การแก้ไข (Editing/Manipulation), เมทาดาทาเวลาและอุปกรณ์ (Metadata: Time/Device), ห่วงโซ่พยาน (chain of custody)

- Bilingual Aligned Transcript: ถอดเสียงสองภาษาแบบ time-aligned พร้อมระดับความเชื่อมั่นของผู้ถอด/ระบบ (confidence) ต่อแต่ละช่วง และบันทึกความกำกวม (ambiguity notes)

- Independent Translation Panel: ผู้เชี่ยวชาญล่ามกฎหมายหลายสำนัก ทำ blind translation + adjudication (inter-rater reliability)

- Pragmatics Report: อธิบาย “uncle” และ “อยากได้อะไร…” ในกรอบความสุภาพไทย/การทูตไม่เป็นทางการ พร้อมตัวอย่างการใช้เชิงสถาบัน

- Timeline Matrix: ตารางเวลาเทียบ log การประชุม, บันทึกโทร, SMS/ข้อความ, หนังสือสั่งการ → ปรับแก้ปี พ.ศ. ให้ถูกต้องและสอดคล้องกันทุกจุด

- Cultural–Diplomatic Norms: บทความ/คู่มือพิธีสารที่ยืนยันการใช้การเจรจาไม่เป็นทางการ/สายตรงในภาวะวิกฤต

บทสรุปเชิงศาล

แม้หลักฐาน (คลิป–คำแปล) ศาลรับฟังไม่ได้ น้ำหนักพยานอ่อน แต่หากกรอบการแถลงแบบปกป้องตนเอง ด้วยกรอบ “สุจริต–สันติวิธี–ไม่ก่อพันธกรณีรัฐ” คดีอาจมีน้ำหนักมากขึ้น และทำให้โอกาสที่จะถูกตีความว่าเป็น “ผิดจริยธรรมร้ายแรง” ลดลงอย่างมาก

แม้คลิปและคำแปลจะถูกยอมรับว่าเชื่อถือได้ และมีการอธิบายบริบททางวัจนปฏิบัติ แต่ศาลยังอาจเห็นว่าถ้อยคำบางช่วงสะท้อนถึง ความไม่ระมัดระวังที่ไม่เหมาะสมสำหรับผู้นำ โดยการตัดสินขึ้นอยู่กับ มาตรฐานการตีความที่ศาลเลือกใช้

เอกสารอ้างอิง

- Berk-Seligson, S. (2009). Coerced confessions: The discourse of bilingual police interrogations. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Brown, P., & Levinson, S. C. (1987). Politeness: Some universals in language usage. Cambridge University Press.

- Coulthard, M., & Johnson, A. (2007/2010). An introduction to forensic linguistics: Language in evidence (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Coulthard, M., May, A., & Johnson, A. (Eds.). (2017). The Routledge handbook of forensic linguistics. Routledge.

- Eades, D. (2010). Sociolinguistics and the legal process. Multilingual Matters.

- Fisher, R., Ury, W., & Patton, B. (2011). Getting to yes: Negotiating agreement without giving in (3rd ed.). Penguin.

- Gibbons, J. (2003). Forensic linguistics: An introduction to language in the justice system. Blackwell.

- Hale, S. (2004). The discourse of court interpreting: Discourse practices of the law, the witness and the interpreter. John Benjamins.

- Jessen, M. (2008). Forensic phonetics. Language and Linguistics Compass, 2(4), 671–711.

- Mason, I. (Ed.). (2009). The translator as communicator. Routledge.

- Olsson, J. (2008). Forensic linguistics: An introduction to language, crime and the law (2nd ed.). Continuum.

- Shuy, R. (2005). Creating language crimes: How law enforcement uses (and misuses) language. Oxford University Press.

- Solan, L. M., & Tiersma, P. M. (2005). Speaking of crime: The language of criminal justice. University of Chicago Press.

- Wadensjö, C. (1998). Interpreting as interaction. Longman.

เกี่ยวกับนักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรองของสมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้

สมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ (SEAProTI) ได้ประกาศหลักเกณฑ์และคุณสมบัติผู้ที่ขึ้นทะเบียนเป็น “นักแปลรับรอง (Certified Translators) และผู้รับรองการแปล (Translation Certification Providers) และล่ามรับรอง (Certified Interpreters)” ของสมาคม หมวดที่ 9 และหมวดที่ 10 ในราชกิจจานุเบกษา ของสำนักเลขาธิการคณะรัฐมนตรี ในสำนักนายกรัฐมนตรี แห่งราชอาณาจักรไทย ลงวันที่ 25 ก.ค. 2567 เล่มที่ 141 ตอนที่ 66 ง หน้า 100 อ่านฉบับเต็มได้ที่: นักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรอง

*สมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ เป็นสมาคมวิชาชีพแห่งแรกในประเทศไทยและภูมิภาคเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ที่มีระบบรับรองนักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรอง

สำนักงานใหญ่: อาคารบ้านราชครู เลขที่ 33 ห้อง 402 ซอยพหลโยธิน 5 ถนนพหลโยธิน แขวงพญาไท เขตพญาไท กรุงเทพมหานคร 10400

อีเมล: hello@seaproti.com โทรศัพท์: (+66) 2-114-3128 (เวลาทำการ: วันจันทร์–วันศุกร์ เวลา 9.00–17.00 น.)