Court Interpreting in the Thai Judicial Context:

A Practical Classification of Roles under Legal and Human Rights Frameworks

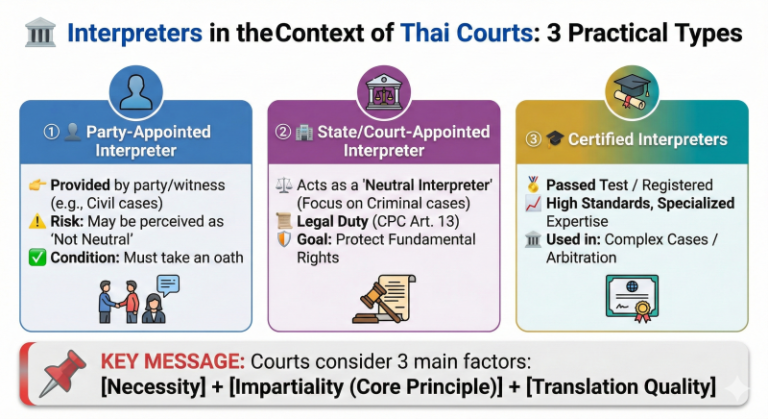

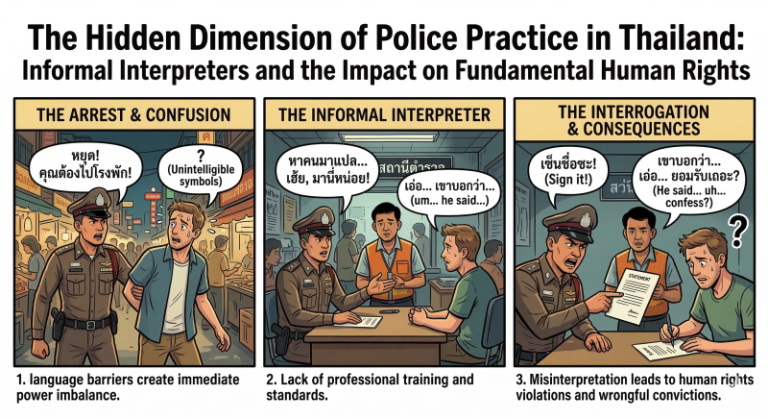

25 January 2026, Bangkok — Interpreters play a critically important role in the administration of justice, particularly in cases where parties, witnesses, or suspects are unable to use the Thai language effectively. However, the Thai legal system does not explicitly prescribe how many categories of court interpreters exist, nor does it provide a rigid statutory classification or ranking system. As a result, understanding the role of interpreters in Thai courts requires an examination of judicial practice, academic literature, and international human rights frameworks.

In practice, interpreters performing duties in Thai courts are commonly classified into three main categories, each with distinct status, functions, and scopes of responsibility.

1. Interpreters Appointed by the Parties

The first category consists of interpreters arranged by the parties or witnesses themselves to facilitate communication for individuals who are unable to adequately understand or use the Thai language. Such interpreters may be used in both civil and criminal proceedings.

Although courts may permit the use of party-appointed interpreters, judges retain the discretion to assess their suitability on a case-by-case basis. Key considerations include the interpreter’s language competence, professional qualifications, and impartiality. If the court determines that an interpreter has a close relationship with one party or displays a tendency to take sides, permission to perform interpreting duties may be denied in order to safeguard the fairness of the proceedings.

2. Interpreters Appointed by State Authorities

The second category comprises interpreters provided by government agencies, typically used when parties are unable to secure an interpreter themselves or when a neutral “court interpreter” is deemed necessary to ensure procedural fairness.

This category is generally used exclusively in criminal proceedings. Section 13 of the Thai Criminal Procedure Code gives suspects and defendants the right to know what charges are against them and what is going on in court in a language they can understand. This principle is also consistent with Thailand’s obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

In practice, interpreters in this group usually receive basic training in court procedures and interpreter ethics from relevant agencies, such as the Department of Rights and Liberties Protection under the Ministry of Justice, social welfare agencies, or certain law-enforcement bodies. However, such training is often short-term and does not involve a comprehensive professional assessment or standardized certification comparable to those administered by professional interpreting organizations.

3. Professionally Certified Interpreters

The third category consists of professionally certified interpreters who have completed structured training, skills assessment, and formal registration with professional translation and interpreting organizations, such as the Southeast Asian professional body for translators and interpreters.

Interpreters in this category are qualified to perform duties in complex or high-stakes cases, including civil litigation, criminal trials, and arbitration proceedings. Emphasis is placed on accuracy, impartiality, ethical accountability, and professional responsibility for the consequences of interpretation. As a result, certified interpreters are often selected for major cases or proceedings that significantly affect the rights and liberties of the parties involved.

Conclusion

Although Thai law does not formally define the number or categories of court interpreters, practical application allows for a functional classification into three main groups: party-appointed interpreters, state-appointed interpreters, and professionally certified interpreters. This practical framework shows that Thai courts value necessity, neutrality, and the quality of interpretation more than formal titles or labels.

Future development of the court interpreting system in Thailand should therefore focus on raising professional standards, expanding in-depth training, and establishing clear accountability mechanisms to ensure that judicial proceedings genuinely protect the rights of all parties within the justice system.

References

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. (1966). International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. United Nations.

- Criminal Procedure Code of Thailand. (As amended). Royal Gazette.

- Mikkelson, H. (2016). Introduction to court interpreting (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Hale, S. B. (2014). The discourse of court interpreting. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

About Certified Translators, Translation Certifiers, and Certified Interpreters of SEAProTI

The Southeast Asian Association of Professional Translators and Interpreters (SEAProTI) has officially shared the qualifications and requirements for becoming Certified Translators, Translation Certification Providers, and Certified Interpreters in Sections 9 and 10 of the Royal Gazette, which was published by the Prime Minister’s Office in Thailand on July 25, 2024. Certified Translators, Translation Certification Providers, and Certified Interpreters

The Council of State has proposed the enactment of a Royal Decree, granting registered translators and recognised translation certifiers from professional associations or accredited language institutions the authority to provide legally valid translation certification (Letter to SEAProTI dated April 28, 2025)

SEAProTI is the first professional association in Thailand and Southeast Asia to implement a comprehensive certification system for translators, certifiers, and interpreters.

Head Office: Baan Ratchakru Building, No. 33, Room 402, Soi Phahonyothin 5, Phahonyothin Road, Phaya Thai District, Bangkok 10400, Thailand

Email: hello@seaproti.com | Tel.: (+66) 2-114-3128 (Office hours: Mon–Fri, 09:00–17:00)

ล่ามในบริบทศาลไทย: การจำแนกบทบาทในทางปฏิบัติภายใต้กรอบกฎหมายและสิทธิมนุษยชน

25 มกราคม 2569, กรุงเทพมหานคร – ล่ามมีบทบาทสำคัญอย่างยิ่งในกระบวนการยุติธรรม โดยเฉพาะในกรณีที่คู่ความ พยาน หรือผู้ต้องหาไม่สามารถใช้ภาษาไทยได้อย่างมีประสิทธิภาพ อย่างไรก็ตาม ระบบกฎหมายไทย มิได้บัญญัติไว้อย่างชัดเจนว่าล่ามศาลมีกี่ประเภท หรือมีการจัดระดับตามตัวบทกฎหมายแบบตายตัว การทำความเข้าใจบทบาทของล่ามในศาลไทยจึงจำเป็นต้องอาศัยการพิจารณาจาก แนวปฏิบัติของศาล เอกสารทางวิชาการ และกรอบสิทธิมนุษยชนระหว่างประเทศ

ในทางปฏิบัติ ล่ามที่ทำหน้าที่ในศาลไทยมักถูกแบ่งออกเป็น สามประเภทหลัก ซึ่งมีสถานะ หน้าที่ และขอบเขตความรับผิดแตกต่างกัน

1. ล่ามที่คู่ความนำมาเอง

ล่ามประเภทแรกคือ ล่ามที่คู่ความหรือพยานจัดหามาเอง เพื่อช่วยแปลภาษาให้แก่ตนหรือบุคคลที่เกี่ยวข้องในคดี โดยเฉพาะในกรณีที่ไม่สามารถสื่อสารภาษาไทยได้อย่างเพียงพอ ล่ามลักษณะนี้พบได้ทั้งในคดีแพ่งและคดีอาญา

แม้ศาลอาจอนุญาตให้ใช้ล่ามที่คู่ความนำมาเองได้ แต่ศาลยังคงมีอำนาจพิจารณาความเหมาะสมเป็นรายกรณี โดยคำนึงถึง คุณสมบัติ ความสามารถทางภาษา และความเป็นกลาง ของล่ามเป็นสำคัญ หากศาลเห็นว่าล่ามมีความเกี่ยวข้องกับฝ่ายใดฝ่ายหนึ่งอย่างใกล้ชิด หรือมีแนวโน้มฝักใฝ่ อาจไม่อนุญาตให้ปฏิบัติหน้าที่ได้ ทั้งนี้เพื่อคุ้มครองความเป็นธรรมของกระบวนพิจารณา

2. ล่ามที่หน่วยงานราชการมอบหมายให้ปฏิบัติหน้าที่

ล่ามประเภทที่สองคือ ล่ามที่จัดหาโดยหน่วยงานของรัฐ ใช้ในกรณีที่คู่ความไม่สามารถจัดหาล่ามเองได้ หรือในสถานการณ์ที่จำเป็นต้องมี “ล่ามกลาง” เพื่อรักษาความเป็นธรรม

ล่ามกลุ่มนี้มักถูกใช้ เฉพาะในคดีอาญา โดยมีฐานทางกฎหมายสำคัญคือ ประมวลกฎหมายวิธีพิจารณาความอาญา มาตรา 13 ซึ่งรับรองสิทธิของผู้ต้องหาและจำเลยในการรับทราบและเข้าใจข้อกล่าวหา รวมถึงกระบวนการพิจารณาคดีในภาษาที่ตนเข้าใจ หลักการดังกล่าวยังสอดคล้องกับพันธกรณีของประเทศไทยภายใต้ กติการะหว่างประเทศว่าด้วยสิทธิพลเมืองและสิทธิทางการเมือง (ICCPR)

ในทางปฏิบัติ ล่ามกลุ่มนี้มักผ่านการอบรมเบื้องต้นเกี่ยวกับกระบวนการพิจารณาคดีและจริยธรรมล่าม จากหน่วยงานที่เกี่ยวข้อง เช่น กรมคุ้มครองสิทธิและเสรีภาพ กระทรวงยุติธรรม หน่วยงานด้านสังคมสงเคราะห์ หรือหน่วยงานบังคับใช้กฎหมายบางแห่ง อย่างไรก็ตาม การอบรมดังกล่าวมักเป็นการอบรมระยะสั้น และไม่ได้มีระบบการทดสอบมาตรฐานทางวิชาชีพในระดับเดียวกับการรับรองโดยองค์กรวิชาชีพ

3. ล่ามรับรองวิชาชีพ (Certified Interpreters)

ล่ามประเภทที่สามคือ ล่ามรับรองวิชาชีพ ซึ่งผ่านกระบวนการอบรม การประเมินทักษะ และการขึ้นทะเบียนกับองค์กรวิชาชีพด้านการแปลและล่าม เช่น สมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้

ล่ามกลุ่มนี้สามารถปฏิบัติหน้าที่ได้ในคดีที่มีความซับซ้อนหรือมีความสำคัญสูง ทั้งคดีแพ่ง คดีอาญา และกระบวนการอนุญาโตตุลาการ โดยเน้นมาตรฐานด้าน ความถูกต้อง ความเป็นกลาง ความรับผิดทางจริยธรรม และความสามารถในการรับผิดชอบต่อผลของการแปล ล่ามรับรองวิชาชีพจึงมักถูกเลือกใช้ในคดีขนาดใหญ่หรือคดีที่มีผลกระทบต่อสิทธิและเสรีภาพของคู่ความอย่างมีนัยสำคัญ

บทสรุป

แม้กฎหมายไทยจะไม่ได้กำหนดประเภทของล่ามศาลไว้อย่างชัดเจนในเชิงตัวเลข แต่ในทางปฏิบัติสามารถจำแนกล่ามในศาลออกเป็นสามกลุ่มหลัก ได้แก่ ล่ามที่คู่ความนำมาเอง ล่ามที่รัฐจัดหา และล่ามรับรองวิชาชีพ การจำแนกดังกล่าวสะท้อนให้เห็นว่า ศาลไทยให้ความสำคัญกับความจำเป็น ความเป็นกลาง และคุณภาพของการแปล มากกว่าป้ายสถานะทางกฎหมายของล่าม

การพัฒนาระบบล่ามศาลในอนาคตจึงควรมุ่งไปที่การยกระดับมาตรฐานวิชาชีพ การฝึกอบรมเชิงลึก และการสร้างกลไกความรับผิด เพื่อให้กระบวนการยุติธรรมสามารถคุ้มครองสิทธิของทุกฝ่ายได้อย่างแท้จริง

เอกสารอ้างอิง (References)

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. (1966). International covenant on civil and political rights. United Nations.

- ประมวลกฎหมายวิธีพิจารณาความอาญา. (แก้ไขเพิ่มเติม). ราชกิจจานุเบกษา.

- Mikkelson, H. (2016). Introduction to court interpreting (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Hale, S. B. (2014). The discourse of court interpreting. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

เกี่ยวกับนักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรองของสมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้

สมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ (SEAProTI) ได้ประกาศหลักเกณฑ์และคุณสมบัติของผู้ที่ขึ้นทะเบียนเป็น “นักแปลรับรอง (Certified Translators) และผู้รับรองการแปล (Translation Certification Providers) และล่ามรับรอง (Certified Interpreters)” ของสมาคม หมวดที่ 9 และหมวดที่ 10 ในราชกิจจานุเบกษา ของสำนักเลขาธิการคณะรัฐมนตรี ในสำนักนายกรัฐมนตรี แห่งราชอาณาจักรไทย ลงวันที่ 25 ก.ค. 2567 เล่มที่ 141 ตอนที่ 66 ง หน้า 100 อ่านฉบับเต็มได้ที่: นักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรอง

สำนักคณะกรรมการกฤษฎีกาเสนอให้ตราเป็นพระราชกฤษฎีกา โดยกำหนดให้นักแปลที่ขึ้นทะเบียน รวมถึงผู้รับรองการแปลจากสมาคมวิชาชีพหรือสถาบันสอนภาษาที่มีการอบรมและขึ้นทะเบียน สามารถรับรองคำแปลได้ (จดหมายถึงสมาคม SEAProTI ลงวันที่ 28 เม.ย. 2568)

สมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ เป็นสมาคมวิชาชีพแห่งแรกและแห่งเดียวในประเทศไทยและภูมิภาคเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ที่มีระบบรับรองนักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรอง

สำนักงานใหญ่: อาคารบ้านราชครู เลขที่ 33 ห้อง 402 ซอยพหลโยธิน 5 ถนนพหลโยธิน แขวงพญาไท เขตพญาไท กรุงเทพมหานคร 10400 ประเทศไทย

อีเมล: hello@seaproti.com โทรศัพท์: (+66) 2-114-3128 (เวลาทำการ: วันจันทร์–วันศุกร์ เวลา 09.00–17.00 น.