The Structural Harm to Thailand’s Justice System:

When Court Interpreters Are Not Professionals and the Rights of Foreign Nationals Are Repeatedly Violated

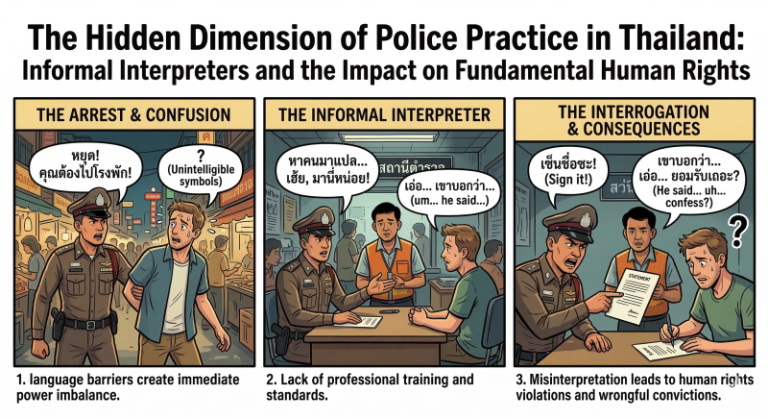

20 January 2026, Bangkok – A fair justice system does not rest solely on well-drafted laws. It depends equally on the effectiveness of every mechanism that enables defendants to understand what is happening and to participate meaningfully in their cases. For foreign nationals who do not understand Thai, court interpreters are one of the most critical mechanisms for access to justice. In practice, however, Thai courts often rely on general bilinguals or individuals who have undergone only brief training, without rigorous assessment of interpreting competence, legal knowledge, or professional ethics. This practice has produced structural harm to the justice system and has led to repeated violations of fundamental rights.

Court interpreting is not a matter of superficial language transfer. It is a foundational condition for the realization of basic rights. Understanding charges, knowing when and how to testify, accepting or contesting evidence, and communicating facts that may affect the outcome of a case all depend on interpretation that is accurate, complete, and impartial. When interpretation is deficient, defendants cannot genuinely exercise their rights, even if an interpreter is formally present in the courtroom (Berk-Seligson, 2002).

A recurring problem in Thai courts is the use of individuals who merely “speak two languages” but lack professional interpreting training. Such individuals often have no systematic preparation in courtroom discourse, legal terminology, or the ethical boundaries of the interpreter’s role. Research in court interpreting demonstrates that interpreting errors are not minor linguistic lapses; they can alter meaning, shift intent, and directly affect how testimony is perceived and weighed by the court (Hale, 2004).

As a State Party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Thailand is bound by international law to guarantee the right to a fair trial. This includes the right of any accused person who does not understand the court’s language to have an interpreter. The requirement is not symbolic. According to the interpretation of the UN Human Rights Committee, “effective” interpretation means a process that enables the accused to understand the substance and legal consequences of the proceedings as a whole, not merely the presence of someone designated as an interpreter (Human Rights Committee, 2007).

The assumption that short-term training can substitute for professional qualifications is a serious misconception. Court interpreters must possess advanced real-time listening and reformulation skills, specialized legal knowledge, a clear understanding of professional role boundaries, and strict ethical discipline. Studies in interpreting ethics emphasize that the absence of qualification standards and accountability mechanisms places interpreters in a precarious position and exposes court users to direct rights violations (Pöchhacker, 2016).

The damage caused by unqualified court interpreting does not end with a single case. Inaccurate interpretation can distort testimony, lead to flawed findings of fact, and ultimately result in judgments based on incomplete or erroneous information. Over time, these kinds of actions hurt the credibility of the courts and make people less likely to trust the justice system, both in the affected countries and around the world. This harm may not always be visible in statistics, but it is evident in the lived experiences of foreign defendants whose voices are never fully or faithfully conveyed in court.

Ultimately, providing qualified court interpreters is not a matter of convenience or budgetary efficiency. It is a minimum requirement of justice itself. As long as Thai courts continue to rely on general interpreters instead of professionally qualified court interpreters, violations of international human rights standards will persist. The problem lies not in the absence of law, but in the failure of the mechanisms that give the law practical meaning.

References

Berk-Seligson, S. (2002). The bilingual courtroom: Court interpreters in the adversarial system. University of Chicago Press.

Hale, S. (2004). The discourse of court interpreting. John Benjamins.

Human Rights Committee. (2007). General Comment No. 32: Article 14—Right to equality before courts and tribunals and to a fair trial. United Nations.

Pöchhacker, F. (2016). Introducing interpreting studies (2nd ed.). Routledge.

United Nations. (1966). International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. United Nations Treaty Series.

About Certified Translators, Translation Certifiers, and Certified Interpreters of SEAProTI

The Southeast Asian Association of Professional Translators and Interpreters (SEAProTI) has officially shared the qualifications and requirements for becoming Certified Translators, Translation Certification Providers, and Certified Interpreters in Sections 9 and 10 of the Royal Gazette, which was published by the Prime Minister’s Office in Thailand on July 25, 2024. Certified Translators, Translation Certification Providers, and Certified Interpreters

The Council of State has proposed the enactment of a Royal Decree, granting registered translators and recognised translation certifiers from professional associations or accredited language institutions the authority to provide legally valid translation certification (Letter to SEAProTI dated April 28, 2025)

SEAProTI is the first professional association in Thailand and Southeast Asia to implement a comprehensive certification system for translators, certifiers, and interpreters.

Head Office: Baan Ratchakru Building, No. 33, Room 402, Soi Phahonyothin 5, Phahonyothin Road, Phaya Thai District, Bangkok 10400, Thailand

Email: hello@seaproti.com | Tel.: (+66) 2-114-3128 (Office hours: Mon–Fri, 09:00–17:00)

ความบอบช้ำของกระบวนการยุติธรรมไทย:

เมื่อล่ามศาลไม่ใช่ล่ามวิชาชีพ และสิทธิของชาวต่างชาติถูกละเมิดซ้ำแล้วซ้ำเล่า

20 มกราคม 2569, กรุงเทพมหานคร – กระบวนการยุติธรรมที่เป็นธรรมไม่ได้ตั้งอยู่บนตัวบทกฎหมายเพียงอย่างเดียว หากแต่ตั้งอยู่บนความสามารถของกลไกทั้งหมดที่ทำให้ผู้ถูกพิจารณาคดีเข้าใจสิ่งที่เกิดขึ้น และสามารถมีส่วนร่วมในคดีของตนได้อย่างแท้จริง สำหรับชาวต่างชาติที่ไม่เข้าใจภาษาไทย ล่ามศาลคือกลไกสำคัญที่ทำให้สิทธิดังกล่าวเกิดขึ้นได้ในทางปฏิบัติ อย่างไรก็ตาม แนวปฏิบัติของศาลไทยที่ยังคงใช้ล่ามทั่วไปหรือบุคคลที่ผ่านการอบรมระยะสั้นโดยไม่ได้ผ่านการประเมินสมรรถนะอย่างเป็นระบบ ได้สร้างความบอบช้ำเชิงโครงสร้างให้แก่กระบวนการยุติธรรม และนำไปสู่การละเมิดสิทธิขั้นพื้นฐานซ้ำแล้วซ้ำเล่า

ล่ามศาลมิได้ทำหน้าที่เพียงถ่ายทอดคำพูดจากภาษาหนึ่งไปสู่อีกภาษาหนึ่ง แต่ทำหน้าที่เป็นเงื่อนไขพื้นฐานของการเข้าถึงความยุติธรรม การเข้าใจข้อกล่าวหา สิทธิในการให้การ การยอมรับหรือโต้แย้งพยานหลักฐาน ตลอดจนการสื่อสารข้อเท็จจริงที่มีผลต่อคำพิพากษา ล้วนต้องอาศัยการแปลที่ถูกต้อง ครบถ้วน และเป็นกลาง หากการแปลคลาดเคลื่อนหรือไม่สมบูรณ์ ผู้ถูกกล่าวหาย่อมไม่สามารถใช้สิทธิของตนได้อย่างแท้จริง แม้ในทางรูปแบบจะมีล่ามอยู่ในห้องพิจารณาก็ตาม (Berk-Seligson, 2002)

ปัญหาที่พบได้บ่อยในศาลไทยคือการใช้บุคคลที่เพียงมีความสามารถในการสื่อสารสองภาษา โดยไม่ได้ผ่านการฝึกทักษะการล่ามเชิงวิชาชีพ การขาดความรู้ด้านกระบวนพิจารณาและศัพท์กฎหมาย รวมถึงการไม่ตระหนักถึงบทบาท จริยธรรม และความเป็นอิสระของล่ามศาล งานวิจัยด้านการล่ามในกระบวนการยุติธรรมชี้ให้เห็นอย่างชัดเจนว่าความผิดพลาดในการแปลไม่ได้เป็นเพียงความคลาดเคลื่อนทางภาษา แต่สามารถเปลี่ยนความหมาย เจตนา และน้ำหนักของคำให้การได้โดยตรง (Hale, 2004)

ประเทศไทยในฐานะรัฐภาคีของ International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights มีพันธกรณีตามกฎหมายระหว่างประเทศในการรับรองสิทธิในการพิจารณาคดีอย่างเป็นธรรม โดยเฉพาะสิทธิของผู้ถูกกล่าวหาที่ไม่เข้าใจภาษาที่ใช้ในศาลที่จะต้องได้รับความช่วยเหลือจากล่ามอย่างมีประสิทธิภาพ คำว่า “มีประสิทธิภาพ” ตามการตีความของคณะกรรมการสิทธิมนุษยชนแห่งสหประชาชาติ มิได้หมายถึงการมีล่ามในเชิงสัญลักษณ์ หากแต่หมายถึงการแปลที่ทำให้ผู้ถูกกล่าวหาเข้าใจเนื้อหาและผลทางกฎหมายของกระบวนการทั้งหมดได้จริง (Human Rights Committee, 2007)

แนวคิดที่ว่าการอบรมระยะสั้นสามารถทดแทนคุณสมบัติของล่ามศาลได้ เป็นความเข้าใจที่คลาดเคลื่อนอย่างร้ายแรง ล่ามศาลต้องมีทักษะการฟังและถ่ายทอดสารแบบเรียลไทม์ ความรู้เฉพาะด้านกฎหมาย ความเข้าใจบทบาทและขอบเขตหน้าที่ ตลอดจนจริยธรรมวิชาชีพที่เคร่งครัด งานศึกษาด้านจริยธรรมการล่ามระบุว่าการขาดมาตรฐานคุณสมบัติและระบบรับผิดรับชอบทำให้ล่ามตกอยู่ในสถานะที่เปราะบาง และเปิดช่องให้เกิดการละเมิดสิทธิของผู้ใช้บริการล่ามโดยตรง (Pöchhacker, 2016)

ผลกระทบจากการใช้ล่ามที่ไม่มีคุณสมบัติไม่ได้จำกัดอยู่ที่คดีใดคดีหนึ่ง แต่สะสมเป็นความเสียหายเชิงระบบ คำให้การที่คลาดเคลื่อนอาจนำไปสู่การวินิจฉัยข้อเท็จจริงที่ผิดพลาด คำพิพากษาที่ตั้งอยู่บนฐานข้อมูลที่บิดเบือนย่อมกระทบต่อความชอบธรรมของศาล และความไม่ไว้วางใจต่อกระบวนการยุติธรรมย่อมขยายตัวทั้งในหมู่ผู้ได้รับผลกระทบและในเวทีระหว่างประเทศ ความบอบช้ำนี้อาจไม่ปรากฏเป็นตัวเลขหรือสถิติที่ชัดเจน แต่สะท้อนผ่านประสบการณ์ของชาวต่างชาติที่ไม่เคยได้รับ “เสียง” ของตนเองอย่างแท้จริงในศาล

ท้ายที่สุด การจัดหาล่ามศาลที่มีคุณสมบัติไม่ใช่เรื่องของความสะดวกหรือการประหยัดงบประมาณ แต่เป็นเงื่อนไขขั้นต่ำของความยุติธรรม ตราบใดที่ศาลไทยยังคงใช้ล่ามทั่วไปแทนล่ามวิชาชีพ การละเมิดสิทธิภายใต้มาตรฐานสากลจะยังคงเกิดขึ้นซ้ำแล้วซ้ำเล่า ไม่ใช่เพราะกฎหมายขาดความชัดเจน แต่เพราะกลไกที่ทำให้กฎหมายมีชีวิตยังคงบกพร่องในระดับโครงสร้าง

References

- Berk-Seligson, S. (2002). The bilingual courtroom: Court interpreters in the adversarial system. University of Chicago Press.

- Hale, S. (2004). The discourse of court interpreting. John Benjamins.

- Human Rights Committee. (2007). General Comment No. 32: Article 14—Right to equality before courts and tribunals and to a fair trial. United Nations.

- Pöchhacker, F. (2016). Introducing interpreting studies (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- United Nations. (1966). International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. United Nations Treaty Series.

เกี่ยวกับนักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรองของสมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้

สมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ (SEAProTI) ได้ประกาศหลักเกณฑ์และคุณสมบัติผู้ที่ขึ้นทะเบียนเป็น “นักแปลรับรอง (Certified Translators) และผู้รับรองการแปล (Translation Certification Providers) และล่ามรับรอง (Certified Interpreters)” ของสมาคม หมวดที่ 9 และหมวดที่ 10 ในราชกิจจานุเบกษา ของสำนักเลขาธิการคณะรัฐมนตรี ในสำนักนายกรัฐมนตรี แห่งราชอาณาจักรไทย ลงวันที่ 25 ก.ค. 2567 เล่มที่ 141 ตอนที่ 66 ง หน้า 100 อ่านฉบับเต็มได้ที่: นักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรอง

สำนักคณะกรรมการกฤษฎีกา เสนอให้ตราเป็นพระราชกฤษฎีกา โดยกำหนดให้นักแปลที่ขึ้นทะเบียน รวมถึงผู้รับรองการแปลจากสมาคมวิชาชีพหรือสถาบันสอนภาษาที่มีการอบรมและขึ้นทะเบียน สามารถรับรองคำแปลได้ (จดหมายถึงสมาคม SEAProTI ลงวันที่ 28 เม.ย. 2568)

สมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ เป็นสมาคมวิชาชีพแห่งแรกและแห่งเดียวในประเทศไทยและภูมิภาคเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ที่มีระบบรับรองนักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรอง

สำนักงานใหญ่: อาคารบ้านราชครู เลขที่ 33 ห้อง 402 ซอยพหลโยธิน 5 ถนนพหลโยธิน แขวงพญาไท เขตพญาไท กรุงเทพมหานคร 10400 ประเทศไทย

อีเมล: hello@seaproti.com โทรศัพท์: (+66) 2-114-3128 (เวลาทำการ: วันจันทร์–วันศุกร์ เวลา 09.00–17.00 น.