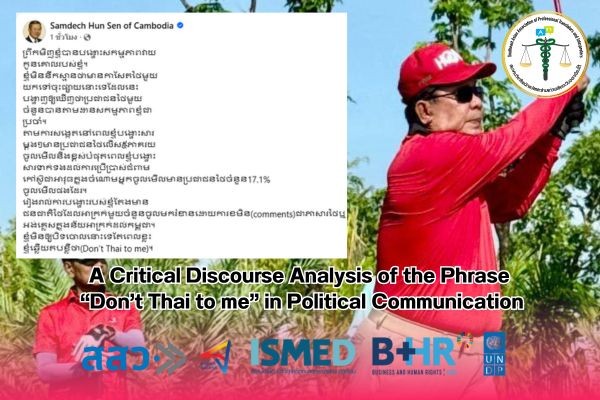

A Critical Discourse Analysis of the Phrase “Don’t Thai to me” in Political Communication

Author: Wanitcha Sumanat, president of the Southeast Asian Association of Professional Translators and Interpreters (SEAProTI)

10 August 2025, Bangkok – This article examines the political and pragmatic implications of the phrase “Don’t Thai to me” as used by Cambodian political leader Hun Sen in an online post. Drawing from Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) frameworks proposed by Fairclough (1995) and van Dijk (1998), the study explores the interplay between linguistic creativity, political symbolism, and socio-cultural framing. The phrase transforms the word “Thai” from a national identifier into a verb with negative connotations, functioning as a rhetorical tool of opposition and boundary-marking in cross-border discourse. The findings indicate that the expression serves multiple functions: as a linguistic play, a political retort, and a symbolic act of resistance, all of which can intensify in-group solidarity while potentially aggravating intergroup tensions.

Keywords: political discourse, Cambodia–Thailand relations, Critical Discourse Analysis, linguistic creativity, political rhetoric

Introduction

Political leaders frequently employ linguistic strategies that serve not only to convey meaning but also to shape social and political realities (Chilton, 2004). In August 2025, former Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen used the phrase “Don’t Thai to me” in a Facebook post responding to hostile comments from some Thai users. The phrase, while unconventional in English syntax, encapsulates both humor and hostility and invites analysis through the lens of political discourse and CDA.

Theoretical Framework

This study employs Critical Discourse Analysis as articulated by Fairclough (1995), which views language as both a social practice and a medium of power relations, and van Dijk’s (1998) socio-cognitive model, which emphasizes the role of mental models in shaping discourse. The analysis also draws from studies on linguistic creativity in political rhetoric (Charteris-Black, 2014) and identity construction in international relations discourse (Wodak, 2015).

Contextual Background

Hun Sen’s remark emerged in the context of heightened Cambodia–Thailand border tensions and increasing social media engagement between citizens of the two nations. His post reported that:

- A significant percentage of viewers of his online posts were Thai (over 5% on average, peaking at 17.1% on certain topics).

- Negative comments in Thai and English frequently targeted Cambodia.

- Rather than deleting these comments, he occasionally replied briefly with “Don’t Thai to me.”

- The remark gained media coverage in Thailand, symbolizing a cross-border exchange of political jabs in the digital sphere.

Discourse Analysis

Linguistic Structure and Wordplay

The phrase mirrors the syntax of “Don’t lie to me” or “Don’t talk to me”, substituting the verb with “Thai” to create a deliberate semantic shift. In this transformation, “Thai” ceases to function purely as a noun or adjective denoting nationality; instead, it becomes a verb connoting undesirable behavior attributed to Thai actors in the context of antagonistic online exchanges.

Pragmatic Functions

The phrase operates on three levels:

- Linguistic Creativity – Using unexpected grammar for humor and memorability.

- Political Retort – Signaling refusal to accept perceived Thai narratives or provocations.

- Boundary-Marking – Reinforcing the “us” (Cambodian) versus “them” (Thai) dichotomy, a strategy common in conflict discourse (Reisigl & Wodak, 2001).

Ideological and Political Implications

In CDA terms, the expression contributes to ideological square strategies (van Dijk, 1998) by emphasizing negative traits of the out-group while implicitly positioning the in-group as resistant and self-reliant. For Hun Sen’s domestic audience, this can strengthen nationalist sentiment; however, for Thai audiences, it may be perceived as derogatory, thereby risking further escalation of online hostility.

Discussion

The use of “Don’t Thai to me” illustrates how political figures can blend humor, aggression, and nationalism in a single phrase. Its virality is enhanced by its bilingual pun, which works in English but draws on cultural and political associations from Khmer and Thai contexts. The phrase’s capacity to polarize reflects broader patterns in digital political communication, where leader–follower interactions are visible, performative, and strategically curated for both domestic and foreign audiences.

Conclusion

Hun Sen’s phrase exemplifies how linguistic creativity can serve as a political weapon in transnational discourse. By turning “Thai” into a verb, he reframed an ethnic/national label into a shorthand for undesirable political behavior, thereby reinforcing in-group solidarity and contesting out-group legitimacy. However, such rhetoric also risks deepening cross-border animosity, highlighting the dual-edged nature of politically charged language in the digital era.

References

- Charteris-Black, J. (2014). Analysing political speeches: Rhetoric, discourse and metaphor. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Chilton, P. (2004). Analysing political discourse: Theory and practice. Routledge.

- Fairclough, N. (1995). Critical discourse analysis: The critical study of language. Longman.

- Reisigl, M., & Wodak, R. (2001). Discourse and discrimination: Rhetorics of racism and antisemitism. Routledge.

- van Dijk, T. A. (1998). Ideology: A multidisciplinary approach. SAGE Publications.

- Wodak, R. (2015). The politics of fear: What right-wing populist discourses mean. SAGE Publications.

About SEAProTI Certified Translators, Certification Providers, and Interpreters

The Southeast Asian Association of Professional Translators and Interpreters (SEAProTI) has published official guidelines and eligibility criteria for individuals seeking registration as Certified Translators, Translation Certification Providers, and Certified Interpreters under Chapter 9 and Chapter 10 of the Royal Thai Government Gazette, issued by the Secretariat of the Cabinet, Office of the Prime Minister, on 25 July 2024 (Vol. 141, Part 66 Ng, p. 100). Full text available at: The Royal Thai Government Gazette

การวิเคราะห์วาทกรรมวิพากษ์ของวลี “Don’t Thai to me” ในการสื่อสารทางการเมือง

ผู้เขียน วณิชชา สุมานัส สมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ (SEAProTI)

10 สิงหาคม 2568, กรุงเทพมหานคร – บทความนี้ศึกษานัยทางการเมืองและการใช้ภาษาในเชิงปฏิบัติของวลี “Don’t Thai to me” ซึ่งสมเด็จฮุน เซน ผู้นำทางการเมืองของกัมพูชา ใช้ในโพสต์ออนไลน์ โดยใช้กรอบการวิเคราะห์วาทกรรมวิพากษ์ (Critical Discourse Analysis: CDA) ตามแนวคิดของ Fairclough (1995) และ van Dijk (1998) เพื่อสำรวจความสัมพันธ์ระหว่างความสร้างสรรค์ทางภาษา สัญลักษณ์ทางการเมือง และการกำหนดกรอบความหมายทางสังคม–วัฒนธรรม วลีดังกล่าวเปลี่ยนคำว่า “Thai” จากการเป็นคำระบุสัญชาติ ไปสู่การทำหน้าที่เป็นคำกริยาที่มีนัยทางลบ ทำหน้าที่เป็นเครื่องมือเชิงวาทศิลป์ในการโต้แย้งและสร้างเส้นแบ่งเชิงสัญลักษณ์ในวาทกรรมระหว่างประเทศ ผลการศึกษาพบว่าวลีนี้มีหน้าที่หลายประการ ได้แก่ การเล่นคำทางภาษา การโต้ตอบทางการเมือง และการกระทำเชิงสัญลักษณ์ของการต่อต้าน ซึ่งสามารถสร้างความรู้สึกร่วมภายในกลุ่ม แต่ก็อาจเพิ่มความตึงเครียดระหว่างกลุ่มได้เช่นกัน

คำสำคัญ: วาทกรรมการเมือง, ความสัมพันธ์กัมพูชา–ไทย, การวิเคราะห์วาทกรรมวิพากษ์, ความสร้างสรรค์ทางภาษา, วาทศิลป์ทางการเมือง

บทนำ

ผู้นำทางการเมืองมักใช้กลยุทธ์ทางภาษาเพื่อไม่เพียงสื่อสารความหมาย แต่ยังเพื่อกำหนดความเป็นจริงทางสังคมและการเมือง (Chilton, 2004) ในเดือนสิงหาคม 2025 สมเด็จฮุน เซน อดีตนายกรัฐมนตรีกัมพูชา ใช้วลี “Don’t Thai to me” ในโพสต์เฟซบุ๊กเพื่อตอบโต้ความคิดเห็นเชิงลบจากผู้ใช้ชาวไทยบางส่วน วลีนี้แม้ไม่เป็นไปตามไวยากรณ์มาตรฐานของภาษาอังกฤษ แต่ผสมผสานอารมณ์ขันและความขัดแย้งไว้ในเวลาเดียวกัน และจึงน่าสนใจต่อการวิเคราะห์ในกรอบวาทกรรมทางการเมืองและการวิเคราะห์วาทกรรมวิพากษ์

กรอบแนวคิดทางทฤษฎี

การศึกษานี้ใช้ การวิเคราะห์วาทกรรมวิพากษ์ (Critical Discourse Analysis) ตามแนวคิดของ Fairclough (1995) ที่มองว่าภาษาเป็นทั้งการปฏิบัติทางสังคมและสื่อกลางของความสัมพันธ์เชิงอำนาจ และ แบบจำลองทางสังคม–ความรู้ของ van Dijk (1998) ที่เน้นบทบาทของแบบจำลองทางจิต (mental models) ในการกำหนดวาทกรรม นอกจากนี้ยังอ้างอิงงานศึกษาว่าด้วย ความสร้างสรรค์ทางภาษาในวาทศิลป์ทางการเมือง (Charteris-Black, 2014) และ การสร้างอัตลักษณ์ในวาทกรรมความสัมพันธ์ระหว่างประเทศ (Wodak, 2015)

ภูมิหลังเชิงบริบท

คำกล่าวของฮุน เซน เกิดขึ้นท่ามกลางความตึงเครียดบริเวณชายแดนกัมพูชา–ไทย และการมีปฏิสัมพันธ์ในสื่อสังคมออนไลน์ระหว่างประชาชนทั้งสองประเทศเพิ่มสูงขึ้น เนื้อหาสำคัญในโพสต์ของเขาระบุว่า:

- ผู้ชมโพสต์ของเขามีชาวไทยเป็นสัดส่วนมากกว่า 5% โดยสูงสุดถึง 17.1% ในหัวข้อการใช้หนังสติ๊กเป็นอาวุธ

- ความคิดเห็นเชิงลบในภาษาไทยและภาษาอังกฤษปรากฏอยู่บ่อยครั้ง

- แทนที่จะลบความคิดเห็นเหล่านี้ เขามักตอบสั้น ๆ ว่า “Don’t Thai to me”

- คำกล่าวนี้กลายเป็นข่าวในสื่อไทย และถูกตีความว่าเป็นการแลกเปลี่ยนเชิงสัญลักษณ์ทางการเมืองข้ามพรมแดน

การวิเคราะห์วาทกรรม

โครงสร้างทางภาษาและการเล่นคำ

วลีดังกล่าวสะท้อนโครงสร้างคล้ายกับ “Don’t lie to me” หรือ “Don’t talk to me” แต่แทนที่จะใช้คำกริยา กลับใช้คำว่า “Thai” ซึ่งทำหน้าที่เป็นการเปลี่ยนความหมายทางไวยากรณ์ โดยทำให้ “Thai” จากคำนามหรือคำคุณศัพท์กลายเป็นคำกริยาที่มีความหมายเชิงลบในบริบทนี้

หน้าที่เชิงปฏิบัติ (Pragmatic Functions)

วลีนี้ทำหน้าที่ 3 ระดับหลัก ได้แก่:

- ความสร้างสรรค์ทางภาษา – ใช้ไวยากรณ์แปลกใหม่เพื่อสร้างภาพจำและความขบขัน

- การโต้ตอบทางการเมือง – แสดงการปฏิเสธที่จะยอมรับการเล่าเรื่องหรือการยั่วยุจากฝั่งไทย

- การสร้างเส้นแบ่ง (Boundary-Marking) – ตอกย้ำความเป็น “เรา” (ชาวกัมพูชา) และ “เขา” (ชาวไทย) ตามกลยุทธ์ในวาทกรรมความขัดแย้ง (Reisigl & Wodak, 2001)

นัยเชิงอุดมการณ์และการเมือง

ในมุมมองของ CDA วลีนี้สอดคล้องกับ กลยุทธ์สี่เหลี่ยมการนำเสนอภาพลักษณ์เชิงอุดมการณ์ (Ideological Square) ของ van Dijk (1998) โดยเน้นคุณลักษณะเชิงลบของกลุ่มภายนอก (out-group) ขณะเดียวกันก็สร้างภาพลักษณ์ของกลุ่มภายใน (in-group) ว่าเข้มแข็งและไม่ยอมจำนน สำหรับผู้ติดตามในประเทศกัมพูชา วลีนี้สามารถสร้างความรู้สึกชาตินิยม แต่สำหรับผู้ฟังชาวไทย อาจถูกมองว่าเป็นการดูหมิ่น ซึ่งอาจกระตุ้นความตึงเครียดในโลกออนไลน์ให้มากขึ้น

อภิปรายผล

การใช้ “Don’t Thai to me” แสดงให้เห็นว่าผู้นำทางการเมืองสามารถผสมผสานอารมณ์ขัน ความก้าวร้าว และชาตินิยมในประโยคสั้น ๆ ได้อย่างไร ความแพร่หลายของวลีนี้ได้รับแรงหนุนจากการเล่นคำสองภาษา (bilingual pun) ที่เข้าใจได้ในภาษาอังกฤษ แต่มีรากทางวัฒนธรรมและการเมืองจากบริบทเขมรและไทย ความสามารถในการสร้างการแบ่งขั้วสะท้อนรูปแบบที่กว้างขึ้นของการสื่อสารทางการเมืองในยุคดิจิทัล ซึ่งปฏิสัมพันธ์ระหว่างผู้นำและผู้ติดตามเป็นสิ่งที่มองเห็นได้ เปิดเผย และมักถูกออกแบบเชิงกลยุทธ์เพื่อตอบสนองทั้งผู้ชมในประเทศและต่างประเทศ

สรุป

วลีของฮุน เซน แสดงให้เห็นว่าความสร้างสรรค์ทางภาษาสามารถทำหน้าที่เป็นอาวุธทางการเมืองในวาทกรรมระหว่างประเทศได้อย่างไร การเปลี่ยนคำว่า “Thai” ให้เป็นคำกริยา ทำให้คำนี้กลายเป็นรหัสแทนพฤติกรรมทางการเมืองที่ไม่พึงประสงค์ในมุมมองของผู้พูด ซึ่งช่วยเสริมความสามัคคีในกลุ่มภายในและท้าทายความชอบธรรมของกลุ่มภายนอก อย่างไรก็ตาม วาทกรรมลักษณะนี้ก็เสี่ยงที่จะเพิ่มความเป็นปฏิปักษ์ระหว่างประเทศมากขึ้น สะท้อนถึงความสองคมของถ้อยคำที่มีน้ำหนักทางการเมืองในยุคดิจิทัล

เอกสารอ้างอิง

- Charteris-Black, J. (2014). Analysing political speeches: Rhetoric, discourse and metaphor. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Chilton, P. (2004). Analysing political discourse: Theory and practice. Routledge.

- Fairclough, N. (1995). Critical discourse analysis: The critical study of language. Longman.

- Reisigl, M., & Wodak, R. (2001). Discourse and discrimination: Rhetorics of racism and antisemitism. Routledge.

- van Dijk, T. A. (1998). Ideology: A multidisciplinary approach. SAGE Publications.

- Wodak, R. (2015). The politics of fear: What right-wing populist discourses mean. SAGE Publications.

เกี่ยวกับนักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรองของสมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้

สมาคมวิชาชีพนักแปลและล่ามแห่งเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ (SEAProTI) ได้ประกาศหลักเกณฑ์และคุณสมบัติผู้ที่ขึ้นทะเบียนเป็น “นักแปลรับรอง (Certified Translators) และผู้รับรองการแปล (Translation Certification Providers) และล่ามรับรอง (Certified Interpreters)” ของสมาคม หมวดที่ 9 และหมวดที่ 10 ในราชกิจจานุเบกษา ของสำนักเลขาธิการคณะรัฐมนตรี ในสำนักนายกรัฐมนตรี แห่งราชอาณาจักรไทย ลงวันที่ 25 ก.ค. 2567 เล่มที่ 141 ตอนที่ 66 ง หน้า 100 อ่านฉบับเต็มได้ที่: นักแปลรับรอง ผู้รับรองการแปล และล่ามรับรอง